#

tree

#

abstract painting

#

impressionist landscape

#

possibly oil pastel

#

handmade artwork painting

#

fluid art

#

forest

#

underpainting

#

painting painterly

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public domain

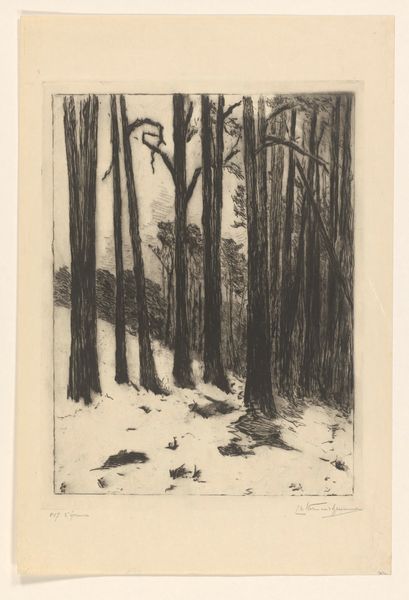

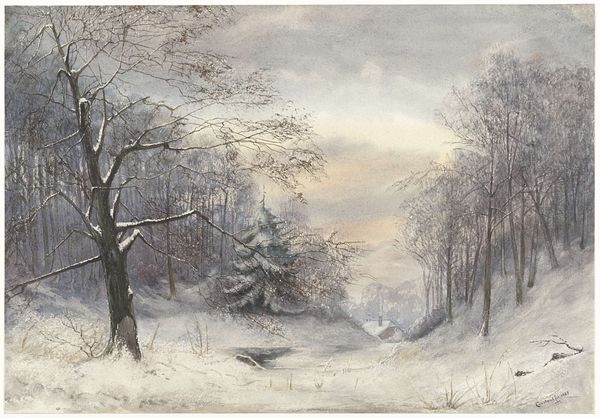

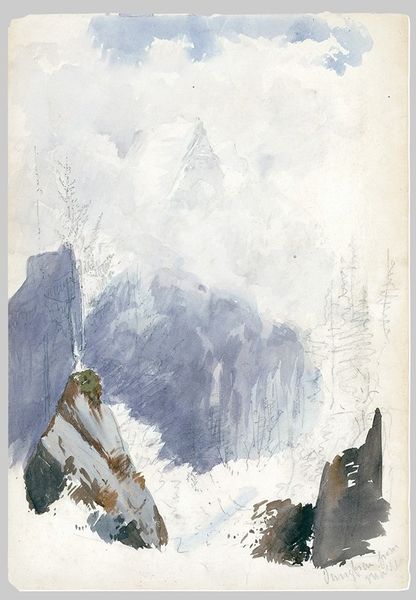

Curator: Let’s delve into Andreas Achenbach’s "Snowy Forest," created in 1835. It’s quite evocative, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Hauntingly beautiful. There’s almost a monochrome effect, which amplifies the stark stillness and that slightly unsettling feeling one gets from an untouched landscape in the grip of winter. Curator: The visible brushstrokes contribute so much to that mood; it's definitely painting 'painterly' as the AI suggests. The technique brings us to Achenbach's working methods— how do you think that intersects with the cultural context of the period? Editor: It's worth thinking about how idealized landscape paintings, even those that seem quite raw, often reinforce notions of national identity and perhaps, ownership. Think about who gets to claim dominion over such pristine scenes and who might be excluded. Curator: That's certainly something to unpack, especially as his style diverged from earlier Romantic ideals that tended towards grandiosity and high drama, but I wonder if the painting can offer clues to the material reality behind this artistic creation? Where were his pigments sourced? What sort of workshop might he have had? Editor: Absolutely crucial questions. And beyond Achenbach himself, we have to ask how landscape art has historically served specific power structures and who the consumers of this type of imagery would have been and what this painting might have represented to them. Was it about communion with nature, or something else? Curator: Those aspects would’ve factored in when affluent patrons commissioned these kinds of paintings. "Snowy Forest," beyond its visual appeal, offers a space to look into those layers. Editor: Agreed. Looking at it with this historical consciousness is more than just academic. It forces us to recognize whose perspectives are historically amplified and to really interrogate whose are missing. Curator: Right—so "Snowy Forest" becomes less about idealized wilderness and more about the social dynamics underpinning artistic production and consumption in the 19th century. Editor: Precisely. It urges us to actively question the narrative behind the landscape—its construction, its purpose, and its ongoing relevance. It offers, more than mere visual appreciation, the possibility of reckoning with the politics of representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.