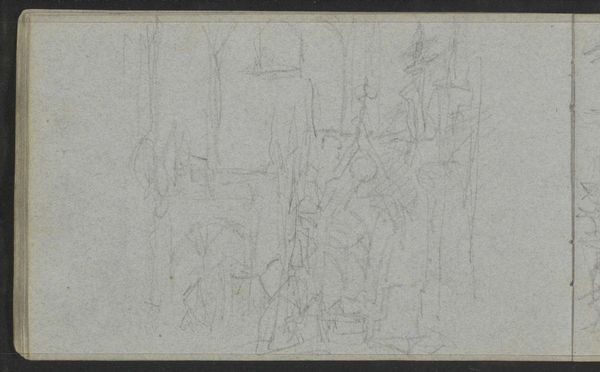

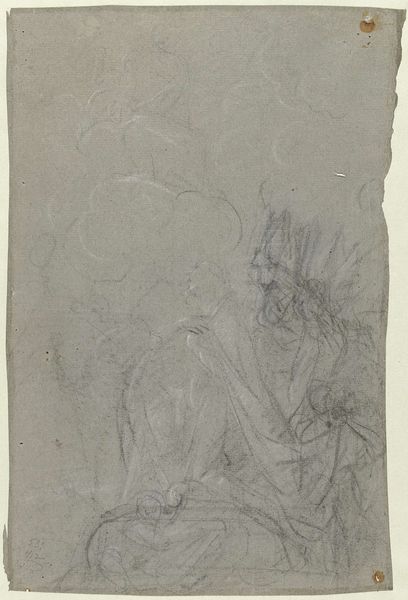

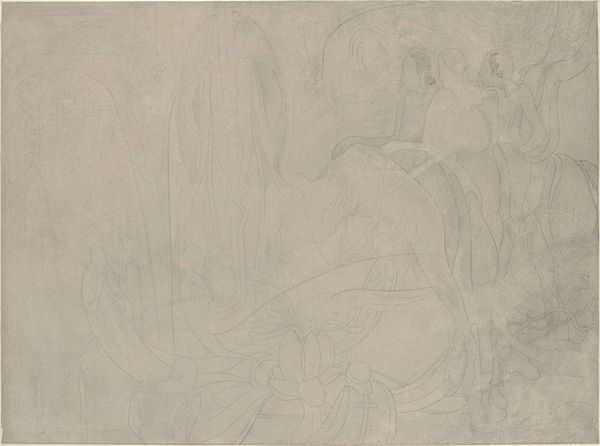

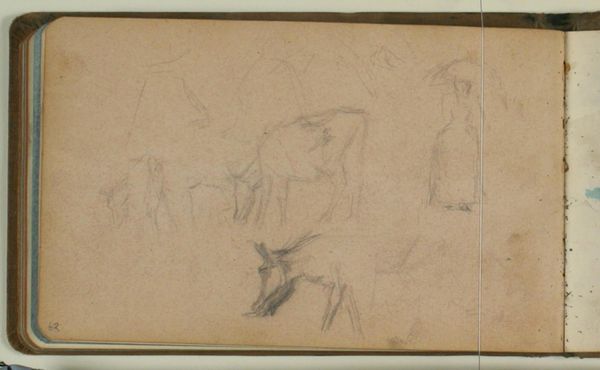

Schets van de onderste helft van het beeldhouwwerk Samson en de Filistijnen 1660s

0:00

0:00

mosesterborch

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil

Dimensions: height 287 mm, width 224 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Moses ter Borch's "Schets van de onderste helft van het beeldhouwwerk Samson en de Filistijnen," a pencil drawing from the 1660s. The figures seem to be caught in a moment of struggle. What strikes me most is the raw energy, even in this preliminary sketch. How do you interpret this work, especially considering the historical context? Curator: This drawing provides a fascinating glimpse into the power dynamics represented in the biblical story of Samson. It is very pertinent to how the 17th century Netherlands saw itself as fighting colonial powers, such as Spain. We see the artist wrestling with ideas of strength, subjugation, and resistance. It's important to remember that Ter Borch lived in a time of intense social and political upheaval; do you see echoes of that in the piece? Editor: Definitely, there's a sense of suppressed violence that could reflect broader anxieties about power and freedom. The choice to focus on the lower half, though, feels deliberate. What could that signify? Curator: Precisely! It anchors the struggle, literally grounding it in the material world. This limited viewpoint might represent the plight of the subjugated, where the full picture of authority remains elusive and overwhelming. What does the unfinished nature of the work suggest to you? Editor: It perhaps highlights the instability and the ongoing nature of such conflicts, with no clear resolution in sight. It almost invites us to complete the story ourselves. Curator: Precisely, and that’s where the activism in art history comes in. It challenges us to consider how these historical narratives continue to resonate, prompting us to examine our own relationships with power, resistance, and representation today. Editor: It’s fascinating to think about this artwork as not just a biblical scene, but a reflection of and commentary on 17th-century society and even on contemporary social issues. Thank you. Curator: My pleasure. It's through these dialogues that we can breathe new life into art history and allow it to challenge us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.