print, photography

#

medieval

# print

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

building

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

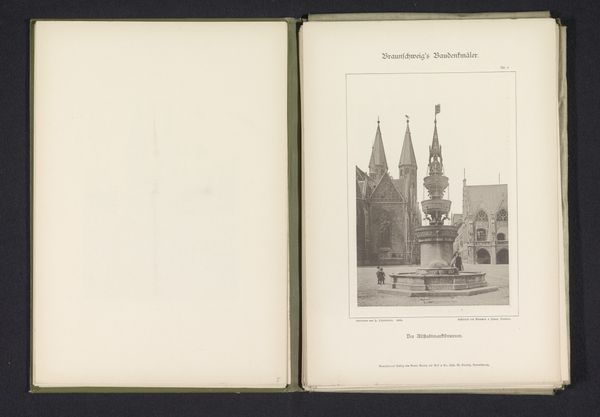

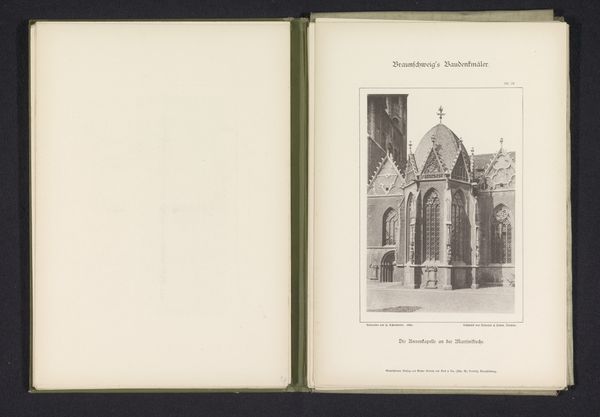

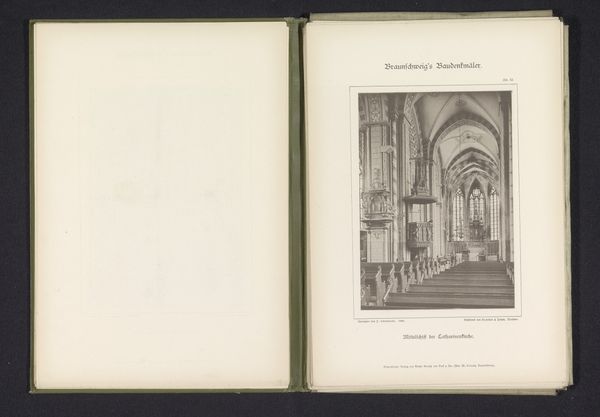

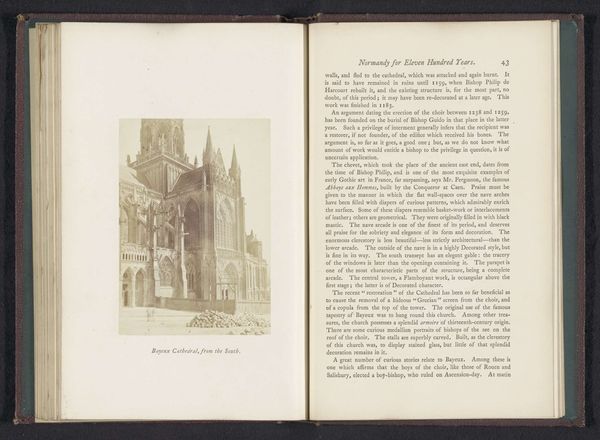

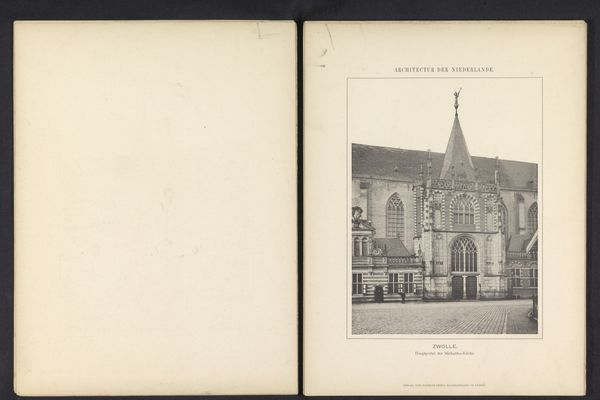

Curator: We’re looking at a photogravure dating to 1892, "Exterieur van de Sint-Martinuskerk te Braunschweig," attributed to J. Schombardt. It depicts the exterior of St. Martin's Church. Editor: It has this overwhelming sense of gravity, doesn't it? Stark grays, the imposing architecture...you can almost feel the chill of the stone. What kind of process generated this print? Curator: As a photogravure, the image starts as a photograph. This is then transferred to a copper plate which is etched to create different tonal depths corresponding to light and shadow. The plate is then inked and printed, resulting in incredibly detailed prints. In essence, the light "writes" the image onto a new tangible printing medium. Editor: Thinking about this process, this means there’s human labor imbedded in this seemingly mass-produced image, something manual transforming light onto the final form. What I am wondering about is the function of depicting religious building by using emerging photogravure? Curator: Religious buildings have always acted as repositories of cultural memory. What strikes me about using a modern printing technique is how it democratizes that memory. The gravure process allows for reproducibility and wider dissemination. More people can carry this image, which represents Braunschweig’s heritage, their faith, with them. Editor: True. Although, considering the era, those “more people” were still a rather elite segment of society with the means to consume such items, a physical artifact representing access. Beyond that, it also offers a controlled and, to some extent, an altered perspective. Curator: Absolutely. This perspective freezes and filters a collective architectural understanding, and, it allows people to carry a piece of this physical building—almost a relic in its own way—back to their parlors. Editor: This photo seems so removed from direct handcraft but at its core is light transforming metal in such a gradual etching and laborious process that it seems, well, medieval. Curator: I see what you mean. On a more general level, its capacity to represent this structure allows an accessibility that wasn't possible before this era. The symbolism transcends the stone and becomes something available to the public as a tangible, reproducible commodity. Editor: It really prompts you to reflect on the interplay between industrial production and artistic legacy. Curator: A dance of progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.