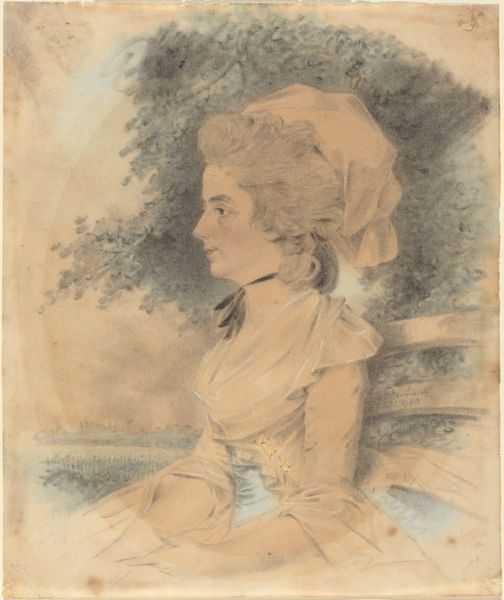

Miss Mary Cruikshank, only sister of James Cruikshank 1781

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: sheet: 9 x 7 1/2 in. (22.9 x 19 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at this print, folks. This is a colour chalk manner print from 1781 by John Downman; it's entitled "Miss Mary Cruikshank, only sister of James Cruikshank." It currently resides here at the Met. Editor: It’s a beautifully melancholic piece, isn't it? The soft pastel colours, the delicate lines... she looks like she's longing for something. There’s an air of wistful waiting to the work. Curator: Definitely a reflection of the times, that pre-revolution aesthetic, you know? Downman captured quite a few fashionable sitters like Mary here; I wonder what it was like to be rendered into one of these delicate portraits. Did she think it made her look romantic and dignified? Editor: It's funny, isn't it? Because now it reads so much more to us. That light blue ribbon around her cap—is it a sign of sophistication or innocence? Or is it merely an ornament for a society portrait meant to broadcast her desirability as a potential match? Curator: Well, portraits then were partly about creating a narrative, setting a person in their social and cultural world. How much say did these subjects truly have? Do we truly see the individuals, or projections constructed for an audience, maybe even themselves? Editor: Perhaps that ambiguity is what still draws us to it. Mary seems lost in contemplation, as though her beauty and privilege, represented so tastefully, might never fulfill the longing for... what? The landscape in the window mimics her mood. Was it intentional or am I projecting my ideas again? Curator: It's likely by design, reflecting the popular Romantic themes of the late 18th century, where emotions and nature became closely intertwined and highly theatricalized, even weaponized, for personal branding. The frame shape itself directs our view... it reminds us of artifice. Editor: A very thoughtful composition, all pointing toward the constructed image of Mary, rather than Mary, herself. Almost heartbreaking in a way. I’ll consider her portrait with an eye toward what her presence tells us of the society that so esteemed her carefully curated image. Curator: Exactly, we can all think of this art not simply as art, but as documents—artifacts of history. So, the next time you consider portraits, maybe reflect less on likeness and more on purpose. What exactly are portraits _for_?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.