Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

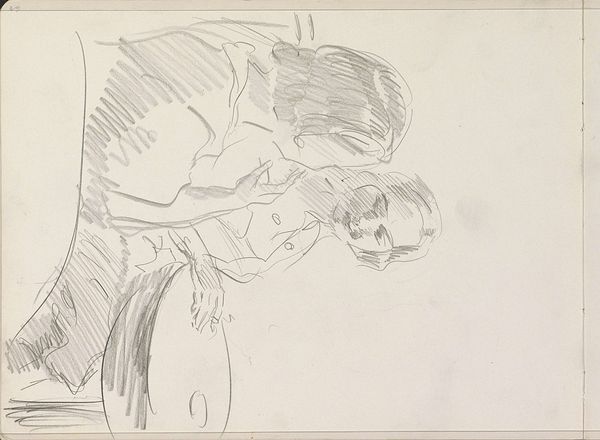

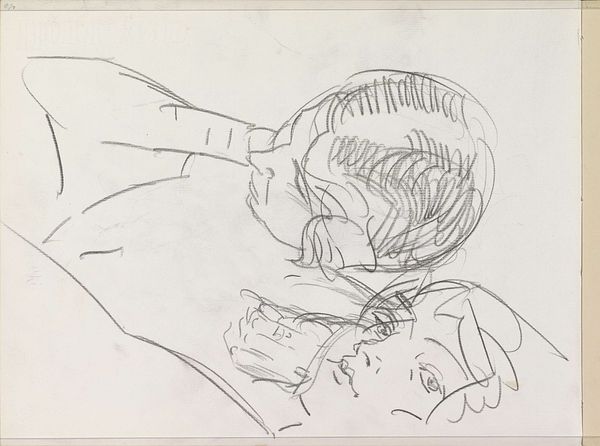

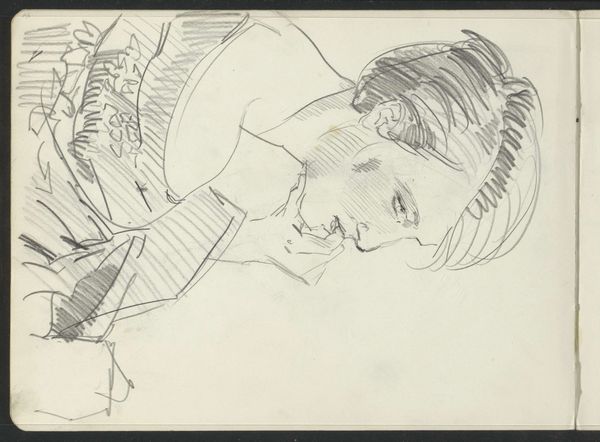

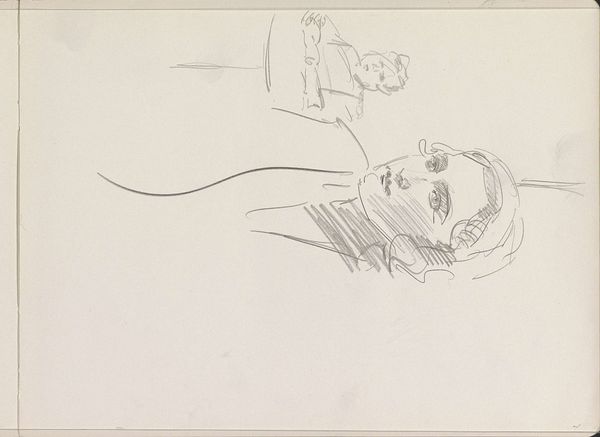

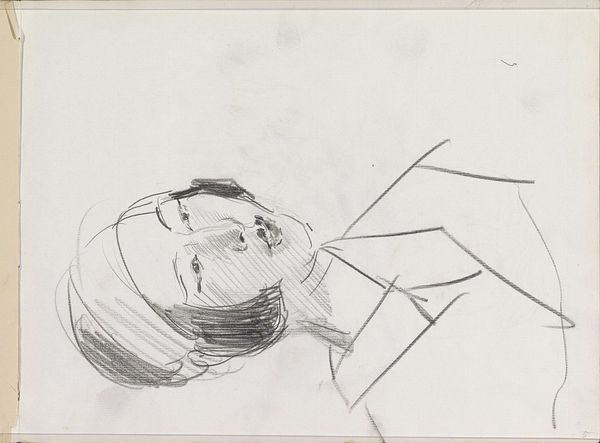

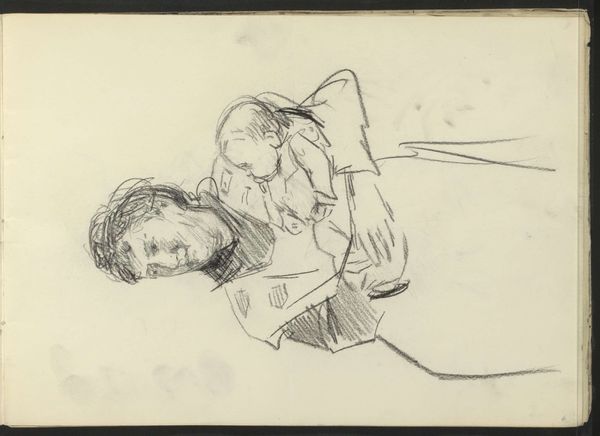

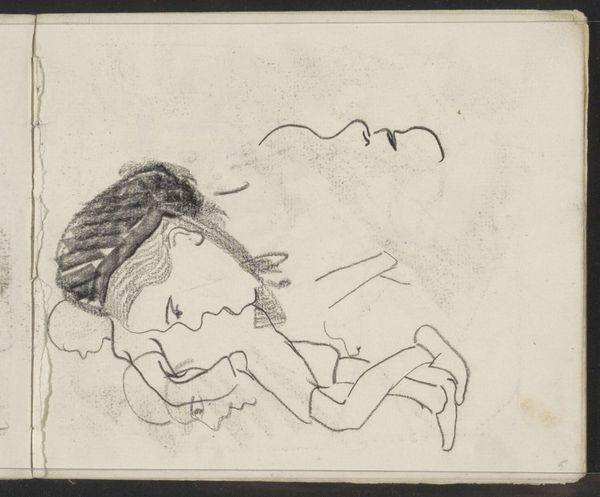

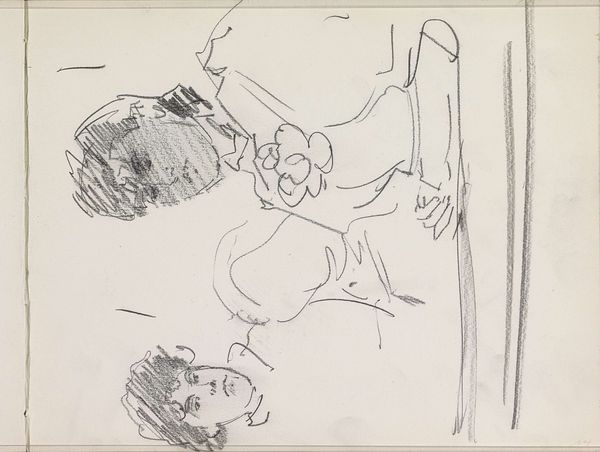

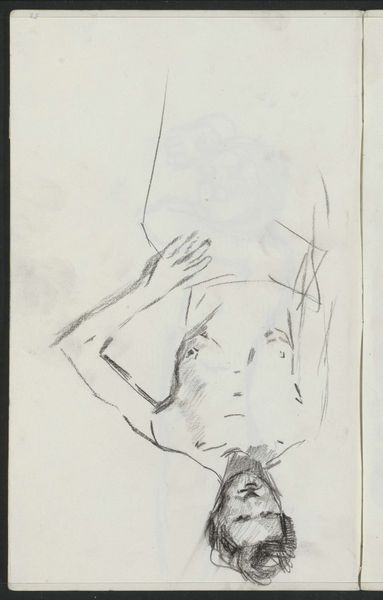

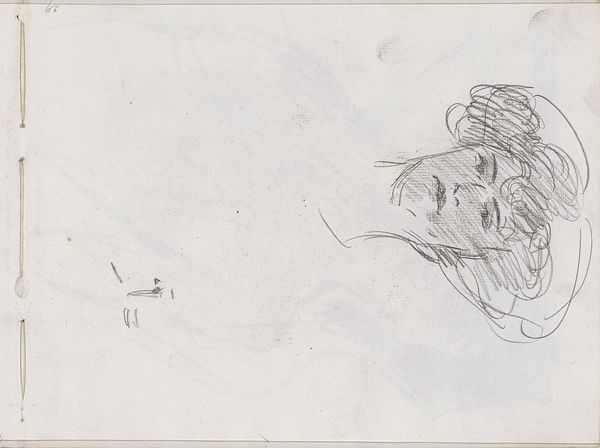

Curator: This drawing is by Isaac Israels, titled “Seated Woman, in Profile”. Created sometime between 1875 and 1934, it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It appears to be a pencil or pen sketch, quite intimate in scale. Editor: My first thought is weariness. She seems to be deeply absorbed in her own thoughts, or perhaps simply exhausted. The looseness of the lines adds to this sense of transience, almost like a fleeting impression caught on paper. Curator: Indeed. Israels was very interested in depicting modern life, capturing everyday scenes and the transient nature of experience. We see this ethos particularly within his treatment of women, exploring the performance of femininity at the turn of the century. Consider, for example, how her averted gaze avoids directly confronting the viewer, complicating the power dynamic traditionally embedded within the portrait genre. Editor: That's a key point. How often do we see women in art being gazed upon, objectified? Here, the passivity could be interpreted as resistance. Her internal world is privileged, becoming a space inaccessible to the viewer's controlling gaze. It seems she dictates her own narrative within this pose. Curator: Precisely, and it encourages a re-evaluation of female agency in art during that time. The details around her dress and the way her hair is piled up also suggest a specific social class. What commentary might this sketch provide regarding gender and class relations within the societal hierarchies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Editor: Perhaps she is a working-class woman in service, caught in a rare moment of repose? The fragility of the sketch could subtly comment on the precariousness of her social position, her existence almost fading into the background, unseen and unacknowledged by the dominant narratives. Curator: This makes me reflect on the power of art, particularly a piece such as this, in highlighting the narratives of people and social classes often omitted from the historical record, provoking conversations around marginalization. Editor: Absolutely, examining pieces such as this is key in creating an art historical canon that truly includes those whose stories are far too frequently obscured.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.