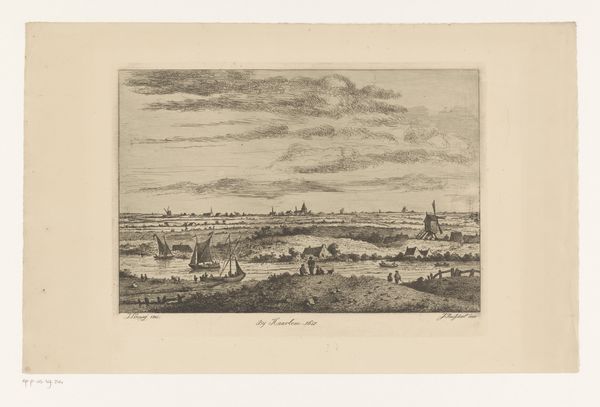

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 255 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

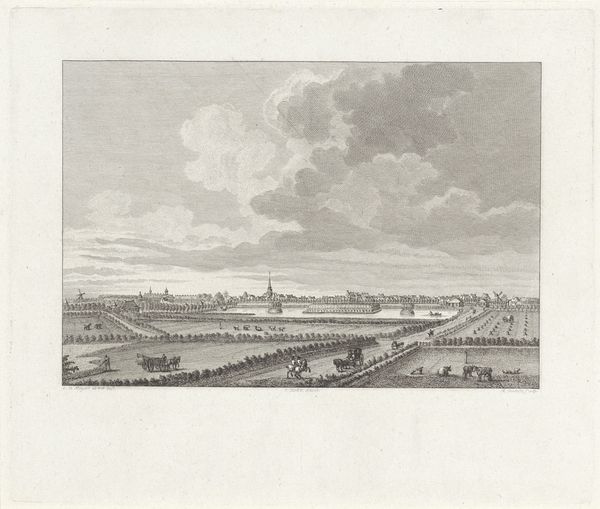

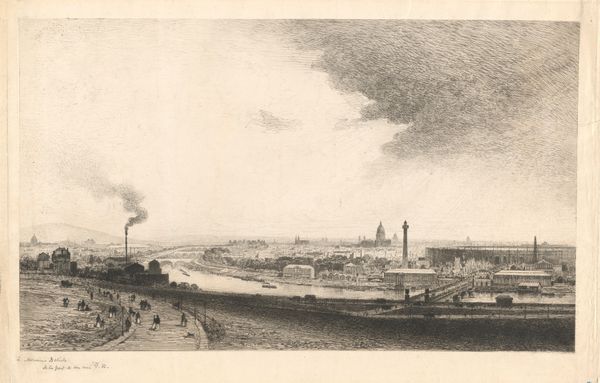

Curator: Before us is “View of Haarlem with the Sint-Bavo Church and the Kruispoort,” an engraving created in 1807 by Izaak Jansz. de Wit, now held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s quite bleak, isn’t it? That monochromatic palette makes the scene feel somber, even a bit lonely. Though there's an impressive clarity in the line work. Curator: That clarity speaks volumes about the printmaking process, doesn't it? The precise incisions on the plate, the controlled application of ink, the pressure exerted by the press... Each step reliant on skilled labor, impacting the final product we consume. Consider the material realities: the quality of the metal, the ink composition, the paper itself! Editor: And speaking of the image itself, note how the imposing Sint-Bavo Church looms over the cityscape. It's more than just a building; it's a symbol of civic pride and religious authority, practically reaching towards heaven. De Wit positions it centrally, almost as a moral compass. Curator: It also highlights the stark class divisions of the time. We see laborers in the foreground working the land, their silhouettes diminutive compared to the towering church, a structure made possible by their collective labor and resources. Editor: The Kruispoort too, acts as a threshold, physically dividing the cultivated safety of the city from the untamed world beyond. Notice the compositional balance, mirroring the church with the city gate, grounding the everyday under divine and social law. Curator: The act of engraving itself speaks to power, the power of reproduction, dissemination of imagery. It was a commercial endeavor, too. These prints would be consumed by locals and travelers alike. I wonder who the intended audience was and their access to these representations of the Dutch landscape. Editor: I can only wonder what those ordinary people pulling the plough thought as that looming symbol of order pierced the sky above their laborious tasks, framed in this piece. The image’s symbolic message can't be divorced from the social reality. Curator: I find myself now appreciating even more, thanks to considering the labor, the materials and the system through which the work came into existence. Editor: Indeed. By focusing on these enduring symbols, and through recognizing the structures they represented then, as well as now, the more profoundly we perceive this landscape and how such symbolic constructions inform our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.