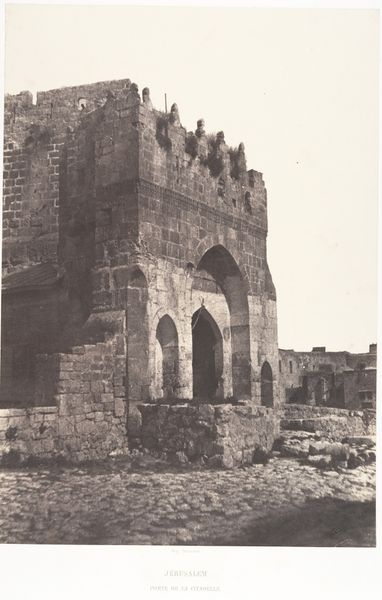

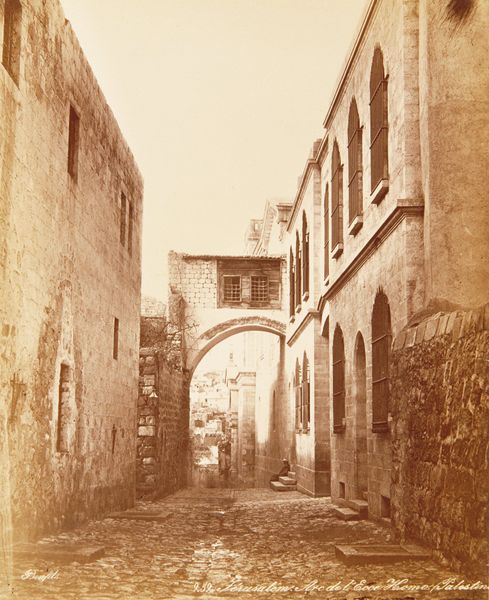

albumen-print, photography, albumen-print

#

albumen-print

#

cityscape photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

landscape photography

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

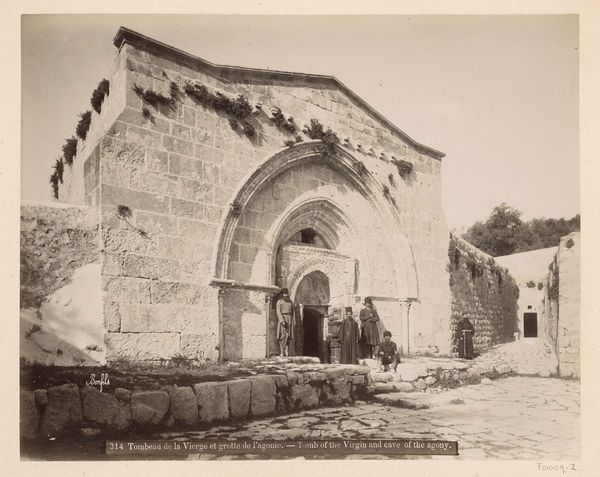

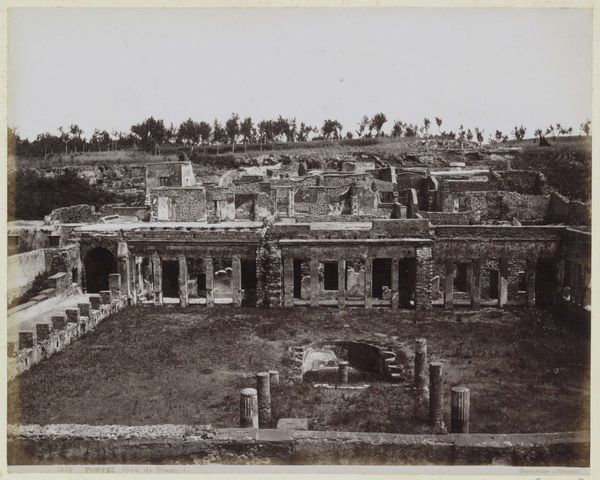

Dimensions: 8 3/4 x 11 3/16 in. (22.23 x 28.42 cm) (image)11 x 14 in. (27.94 x 35.56 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

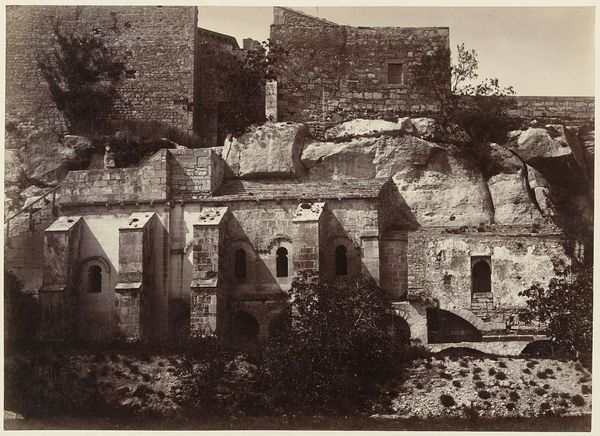

Editor: So, here we have Fèlix Bonfils’s albumen print, "Tombeau d'Elie a Jerusalem," taken sometime in the 1870s. It presents this very weathered, ancient-looking structure… almost like a stage set. It feels… theatrical, even. How do you interpret this work through a historical lens? Curator: It's fascinating how you immediately pick up on the 'stage set' quality. Bonfils was very much a part of a 19th-century phenomenon: using photography to document and, perhaps more subtly, to construct a specific narrative of the 'Orient.' How do you think his choice of composition and printing medium shapes the viewer’s understanding of Jerusalem and its religious sites? Editor: Well, the albumen print gives everything a sepia tone, instantly signaling "past." And by framing the structure so centrally, with those very geometric, almost stark surroundings, it feels staged. Is that orientalism at play? Curator: Exactly! The seemingly objective record of photography was often employed to reinforce colonial ideas. Bonfils wasn't just recording a site; he was participating in a broader visual project. Do you see how this image, intended for a European audience, might reinforce existing perceptions of the East as timeless, exotic, and separate from the modern West? Editor: That makes a lot of sense. So the photograph isn’t just documentation, it’s an active participant in shaping cultural understanding. It makes you wonder what was cropped out, or what wasn't considered "worthy" of the shot. Curator: Precisely. It’s in those omissions and choices that the real politics of imagery emerge. Considering who Bonfils was selling these images to, what was *their* perception of the ‘Orient’, and how does that impact the image’s ‘value’ as an art piece, and a historic artifact? Editor: This really challenges my understanding of historical photographs as simply neutral records. Curator: That shift in perspective is exactly the point. Now, every time we look at such an image, we can remember the powerful ways images construct and negotiate the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.