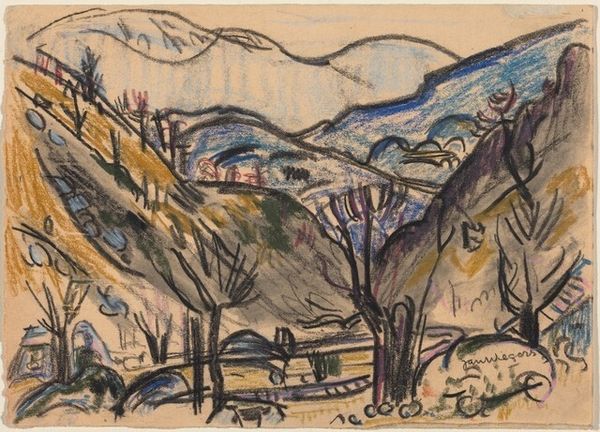

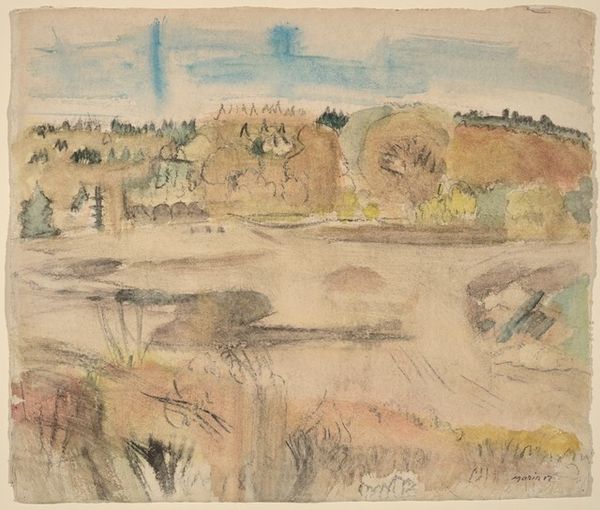

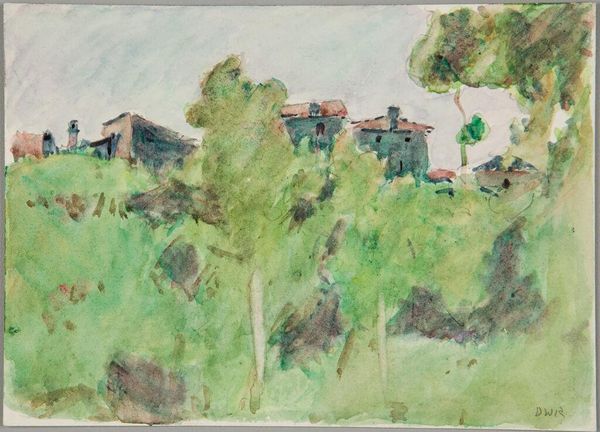

painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

abstraction

#

post-impressionism

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

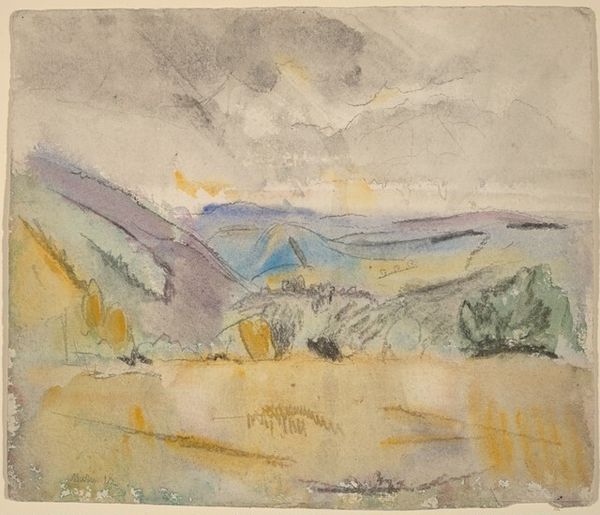

Curator: We're looking at Émile Bernard's "Paysage aux alentours de Pont-Aven," a watercolor and colored pencil piece from 1889. Editor: The initial mood is quite somber, wouldn’t you say? The muted colors, the sketch-like quality. There's a dreamlike, almost melancholy feel about it. Curator: Considering Bernard's milieu, a place like Pont-Aven would have teemed with artistic experimentation, impacting his material and aesthetic choices significantly. These post-impressionists were investigating the very nature of seeing. Editor: Absolutely. Look at how Bernard represents those figures, possibly peasant women. Their dark clothing contrasts sharply with the golden-green landscape, giving them a symbolic weight. Do they represent tradition against change, or some kind of mourning for the past? Curator: What's interesting here is that by reducing figures and forms to such essential lines, Bernard explores the raw process of representation. The blurring of watercolor shows us how much the medium itself is telling the story, moving from impressionistic to abstracted forms through the materiality of it. Editor: The rain in the background certainly draws me in. It isn't simply weather, is it? Instead it becomes a visual metaphor; a symbolic weeping, a subtle warning, perhaps even an evocation of purification. Curator: I would venture that such abstraction, evident in both subject and medium, questions not only art's making but also consumption's effect on artistic value, since its deliberate lack of conventional realism flies against that established order of landscape painting. Editor: But by simplifying the scene, he allows archetypes to emerge. Consider the trees—they're almost primal forms. The composition itself has a familiar rhythm, offering both comfort and, strangely, discomfort. Curator: And in thinking of his working process as a conscious process of abstracting the already available imagery through drawing and watercolor paints, Bernard turns art making itself into commodity assessment. It questions production in relation to inherent symbolic value as one becomes reliant on another. Editor: What fascinates me is how Bernard takes the observed world around Pont-Aven, infuses it with symbolism that can resonate across eras, inviting us to contemplate on cycles and feelings that might otherwise pass unnoticed. Curator: True, that’s art-making. But its essence, it's value is not about a singular symbol—it lies in asking what labor constructs an item so valued, and whose vision it truly represents to begin with. Editor: Ultimately, I come away pondering on memory and transformation; Bernard coaxes me to regard how landscapes may evolve but symbols—both intimate and cultural—persist across the generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.