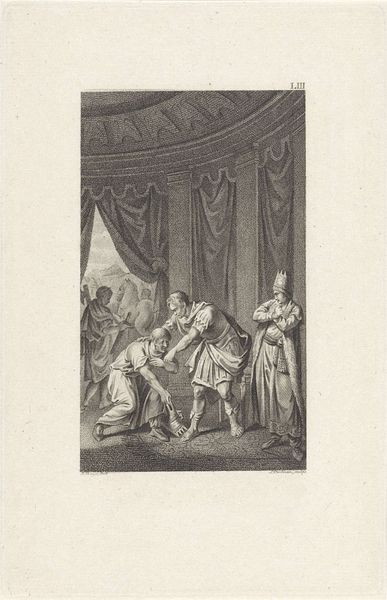

engraving

#

neoclacissism

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

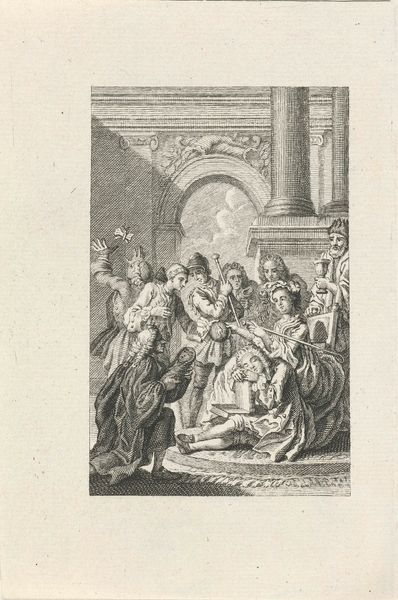

Curator: I'm immediately struck by the raw emotion in this print. The stark black and white only amplifies the sense of tragedy, don't you think? Editor: Indeed. This is “A Mother Offers Her Dead Child as a Meal,” an engraving created in 1797 by Reinier Vinkeles, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. The narrative, as disturbing as it is, speaks volumes about the brutal realities of conflict. Curator: It certainly does. The visual vocabulary of neoclassicism seems at odds with the sheer horror of the scene. Notice how Vinkeles uses classical drapery and architectural elements. It gives a sense of timelessness, perhaps suggesting that these atrocities are eternal features of human society. The very graphic style and clarity creates distance, which only deepens the sense of shock for a modern viewer. Editor: Precisely. Contextualizing this image, we understand it responds to specific historical traumas. This visual representation, rendered in stark black and white, places on view the anxieties related to famine, siege, and the collapse of societal order, events often seen during times of war and political upheaval. The mother's desperation embodies the intersectional vulnerabilities that women, specifically, face. Curator: The image resonates deeply within a collective visual memory, particularly how maternal figures and dead children populate not just the Old Testament but Greek and Roman tragedies as well. This print is yet another symbolic embodiment of extreme sacrifice, wouldn't you say? Editor: Definitely. The very act of engraving—making an incision to transfer and fix this act—could suggest the permanent scar on societal memory produced by similar events. And what about the gaze of those men at left? The whole arrangement implicates male aggression. Curator: It is impossible not to notice that. The positioning is brilliant – notice the muscular figures crowding behind him, almost egging him on to accept her unthinkable offer. It becomes an allegory for not just desperation but corrupted masculinity. Editor: Absolutely. It also makes you wonder about art's role during and after trauma. Does such an image serve as a warning, or could it further ingrain such harmful ideas by constantly putting them in front of our eyes? It's a difficult but crucial point to remember when we look back at art history. Curator: A sobering thought. Editor: Yes. And with that note, may we reflect further on Vinkeles' historical, disturbing allegory for collective vulnerability during conflicts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.