silver, metal, metalwork-silver, sculpture

#

silver

#

metal

#

metalwork-silver

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

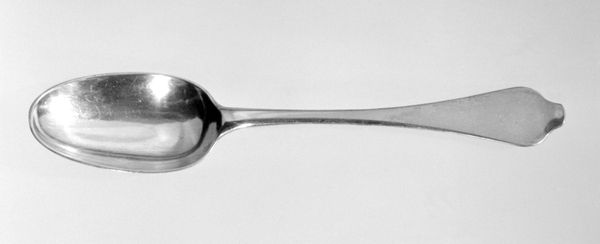

Dimensions: Length: 8 in. (20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

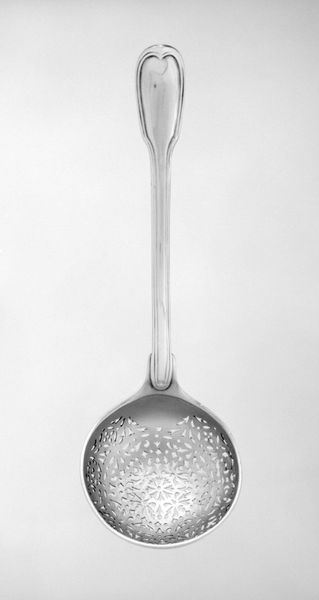

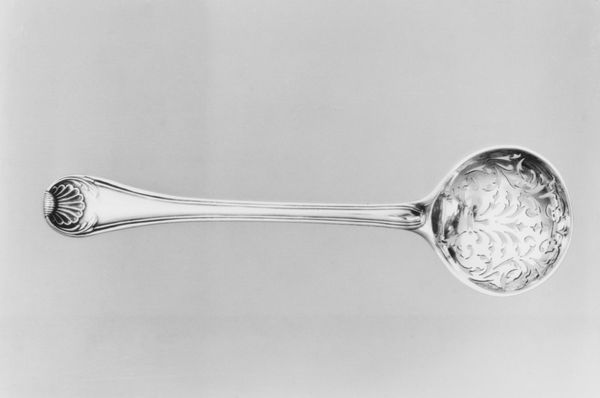

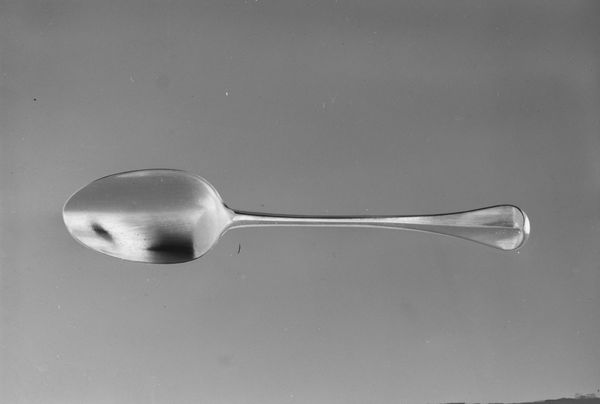

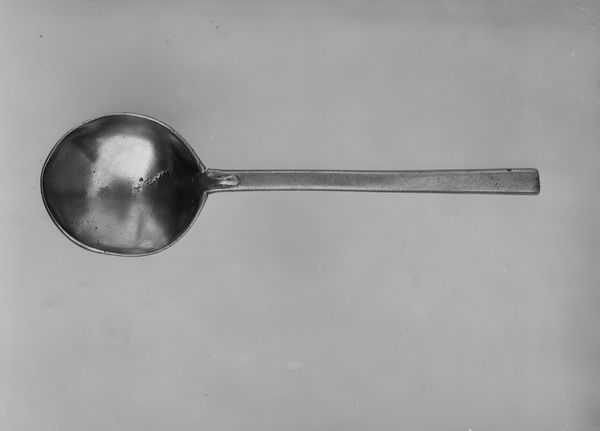

Curator: This exquisitely crafted object before us is a sugar spoon created by Jean Chaslon in 1766. It is silver metalwork, a refined example of decorative art currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It's lovely! It’s so delicate. The swirling floral pattern within the bowl feels almost whimsical against the stark, polished silver. It hints at hidden indulgence, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. When considering such objects, we have to understand sugar's changing role. In 1766, it was less of a staple and more of a luxurious commodity—something deeply tied to trade, colonial exploitation, and, therefore, power dynamics. Who could afford this spoon and the substance it portioned out? Editor: Precisely. And the form itself, this delicate spoon, signals so much about class. It represents a certain level of domestic labor and who likely would have handled it, hinting at gender and social standing, within that context. The serving of sugar wasn’t simply about sweetness. Curator: No, it was a ritual embedded in a complicated web of socioeconomic factors, a way of signaling status and wealth. Silver, of course, being yet another visible signifier. Think of the silversmith's place within that society, his skilled labor catering to elite tastes and reinforcing the status quo through these material objects. Editor: It's almost like this tiny spoon encapsulates the era. I keep thinking of the visual contrast between the bowl filled with bright, refined sugar and the stark realities behind its production. That ornamental floral design takes on a different resonance knowing that. Curator: A necessary, if uncomfortable, relationship to consider. Even something as seemingly simple as a spoon becomes a site where we can unpack layered meanings about wealth, labor, and global exchange in the 18th century. Editor: It serves as a good reminder to really look—beyond the gleam and graceful lines, but at who had access, and at what cost, to everyday fineries such as this. Curator: A potent reminder that the aesthetic and the political are always intertwined.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.