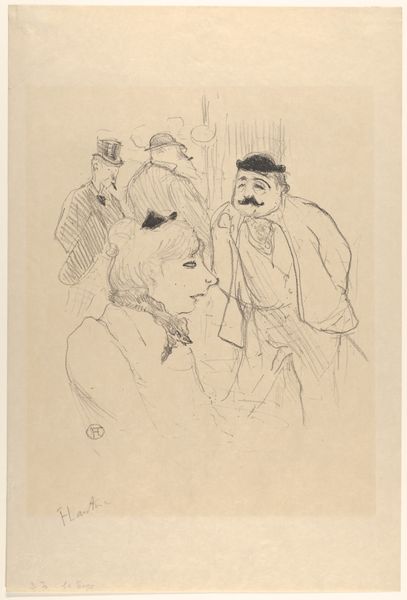

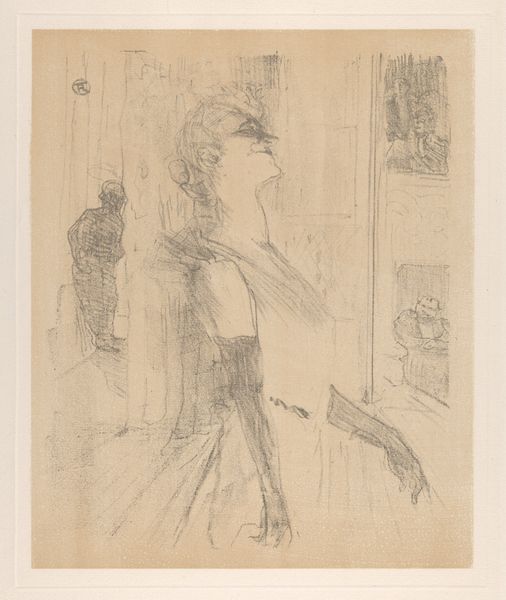

Marcelle Lender and Eva Lavalliére in a Revue at the Variétés 1895

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: 12 in. × 9 13/16 in. (30.5 × 25 cm) Sheet: 19 5/16 × 13 3/8 in. (49.1 × 34 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

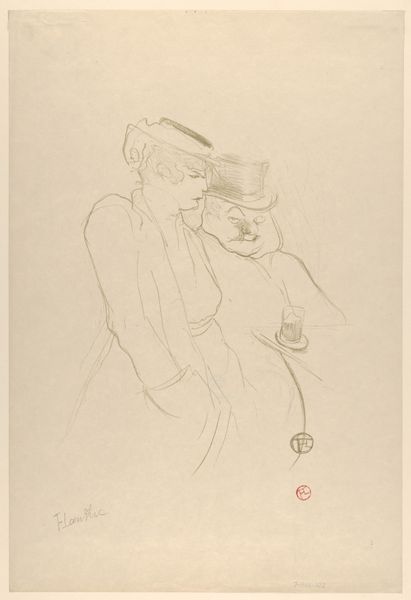

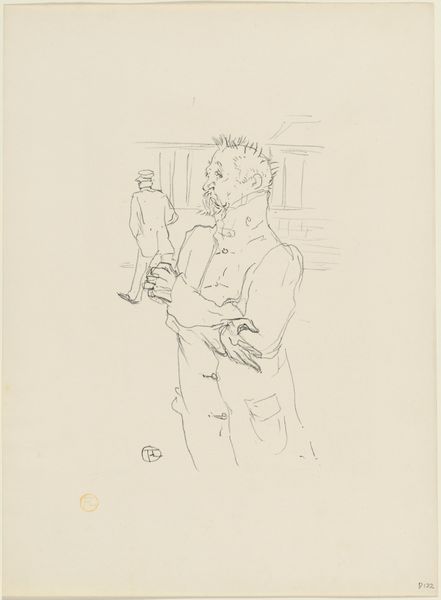

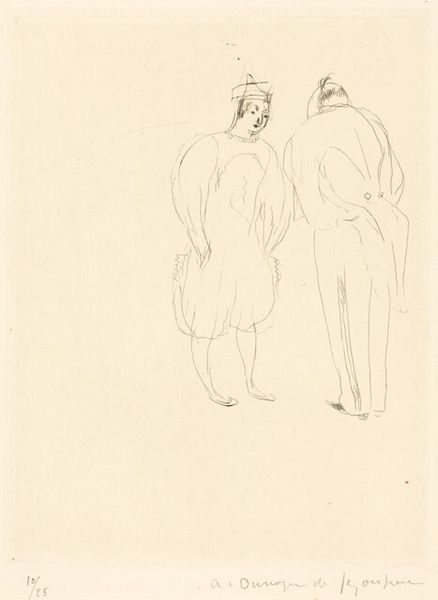

Curator: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec sketched this piece in 1895. It’s titled "Marcelle Lender and Eva Lavallière in a Revue at the Variétés," currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look closely—it’s pencil on paper, a medium he used frequently to capture the energy of Parisian nightlife. Editor: It has such an airy, ephemeral quality. The swift pencil strokes give a real sense of movement, even a fleeting impression of the music and chatter of the Variétés. It's almost as if you’re peeking in on a private moment. Curator: Right. It’s a study, not a fully realized painting. Notice how some areas are densely shaded, while others are just suggested outlines. This drawing is interesting from a craft standpoint, as it’s indicative of the preparatory stage of poster design: pencil as a quick means to capture the scene for later lithographic application. Editor: What's fascinating is that it captures the burgeoning performative identities of women at the fin de siècle, though. These revues were pivotal spaces where gender roles were both reinforced and subtly subverted, particularly considering the social freedoms they afforded female performers. Curator: Precisely, and Lautrec, working as a draughtsman for commercial posters, was dependent on representing celebrities of the stage to cultivate a particular image and brand in wider circulation. Editor: Yes! We can observe it as an exchange of visibility between artist, performer, and the public, negotiating anxieties and fascinations around femininity, spectatorship, and celebrity culture in late 19th-century Paris. What does it mean for an artist to capitalize from visibility and publicity, or even intrude in those spaces? Curator: Also, given Lautrec’s position as an outsider—his physical condition shaped his entire artistic production and identity—do we have a glimpse into what may be a certain fascination with performance? A commentary through visual means. Editor: Perhaps. He occupied a unique space himself, documenting those who performed for a living while, in essence, his artwork was a continuous, and heavily publicized performance of identity. This drawing isn't just a portrait, it’s a snapshot of cultural anxieties, performed on stage and paper alike. Curator: Food for thought. Looking closely at the details, the texture he creates with minimal means speaks volumes about the era's values in artistry and mechanical reproduction. Editor: Absolutely. And it is important to ask questions, to delve into those contexts that might otherwise go unseen in the delicate strokes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.