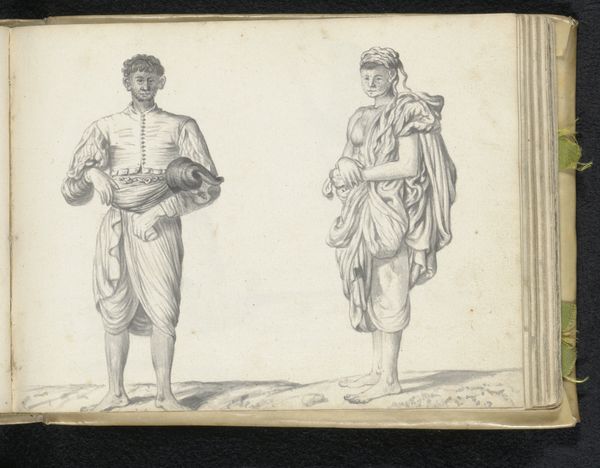

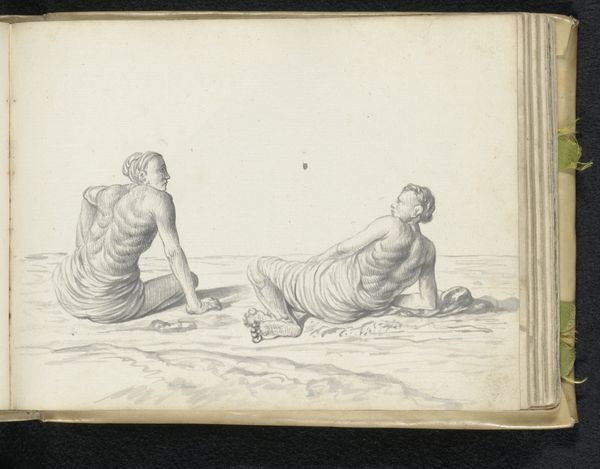

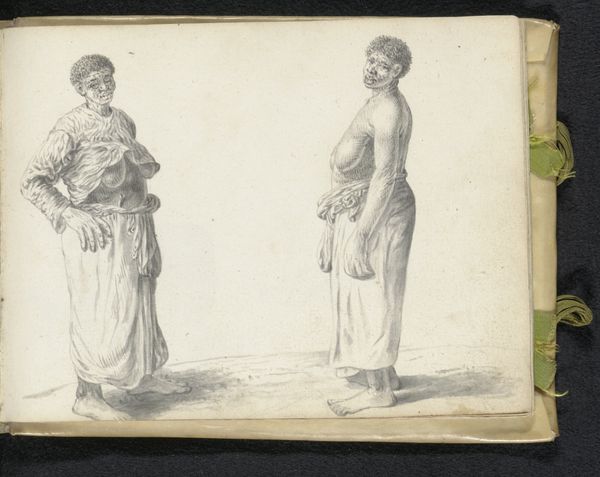

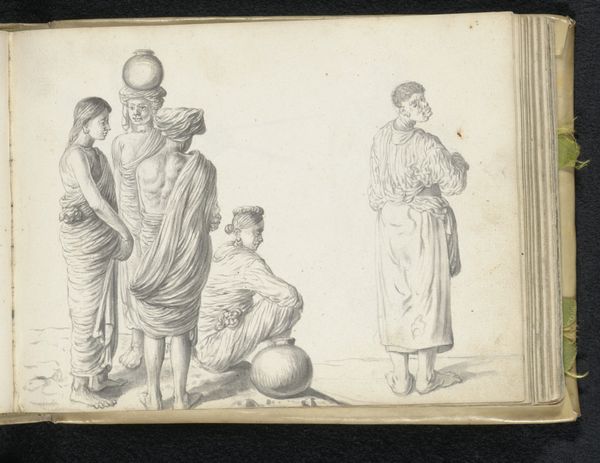

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

figuration

#

coloured pencil

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 196 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

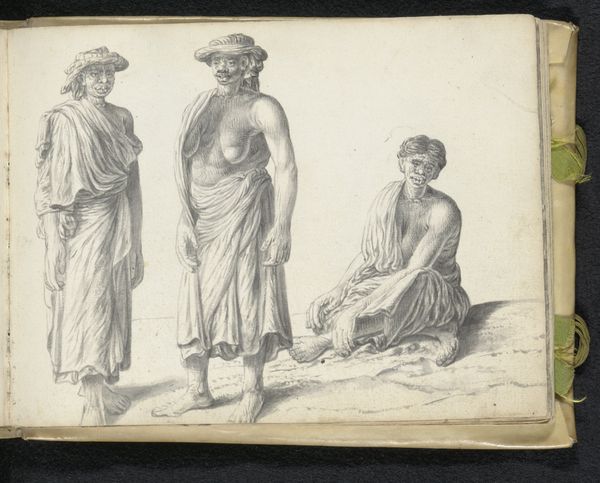

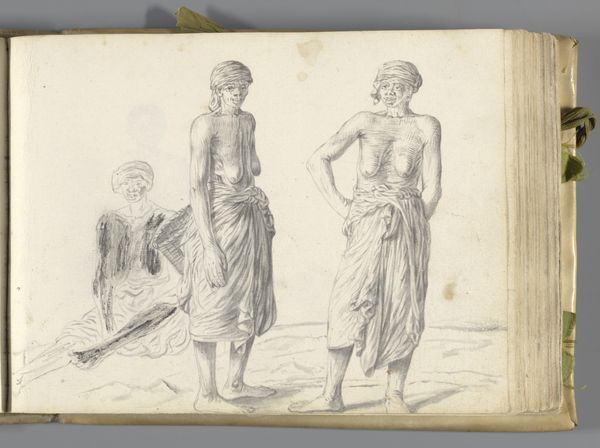

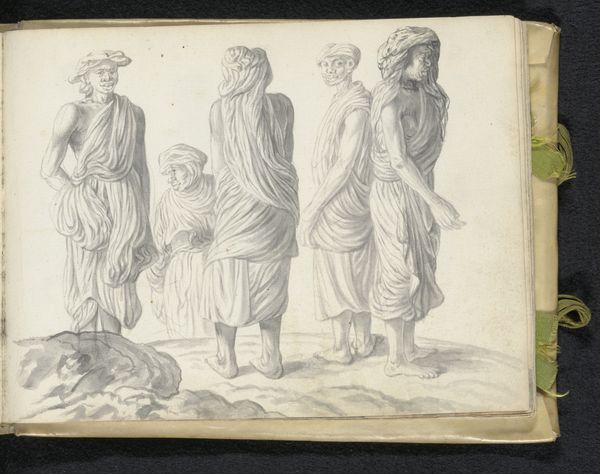

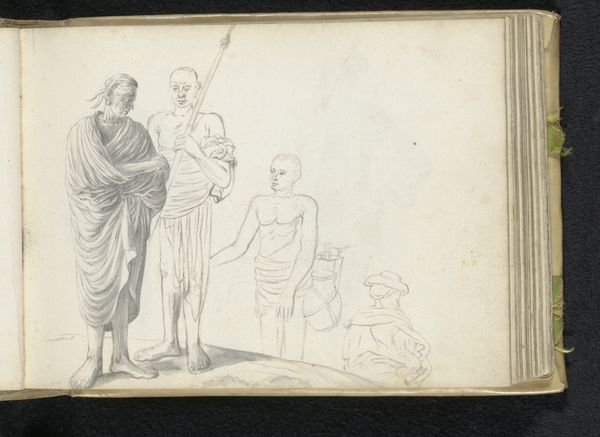

Curator: Esaias Boursse’s drawing, “Three wet nurses and two infants,” created in 1662, immediately strikes me as serene yet subtly complex. The pencil work creates such soft gradations of tone and form. Editor: Soft, yes, but also imbued with a sharp class consciousness. Look at the attire and the almost transactional nature of the poses. Boursse, operating within the Dutch Golden Age, was certainly aware of the socio-economic realities underpinning the act of wet nursing. Who are these women, and for whom do they labor? Curator: I see your point, certainly. Though the formal aspects suggest otherwise, perhaps it invites a closer reading of line, posture and space? Take the nurse on the right; her gaze directed toward us. There's a quietness in how her face is drawn. This contrasts dramatically with how Boursse composes her body – more robust than the one who stands back-to-us. I am particularly drawn to the tactile contrast rendered via line; look how Boursse differentiates the soft texture of the child’s skin from the fabric it is wrapped within, or the coarse bundle worn by the woman to the left! Editor: Exactly. That labor is rendered through that particular combination of textiles; a form of early worker's uniform. How was this image produced, distributed? Was it a sketch for something larger, or a commodity in its own right? What’s the relationship between the hand that drew this, and the bodies depicted within? Curator: Good question, that tension definitely exists. However, if you look beyond the representation of labor and materiality, you can see an engagement with more pure forms, more simplified geometries within each figure. It reminds me of some classical figure studies... Editor: I see a society structured by gendered labor; a visual record, however partial, of the domestic economy in 17th century Netherlands, yes but perhaps also something far darker implicit in what these drawings attempt to show or choose not to reveal. Curator: Indeed, perhaps we are seeing it now as a visual artifact marked with socio-political implications, however filtered through time. Editor: Ultimately, art confronts and questions more than it answers. Thanks to the formal structure and deliberate artistry present here, we have so many compelling lines of inquiry.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.