print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

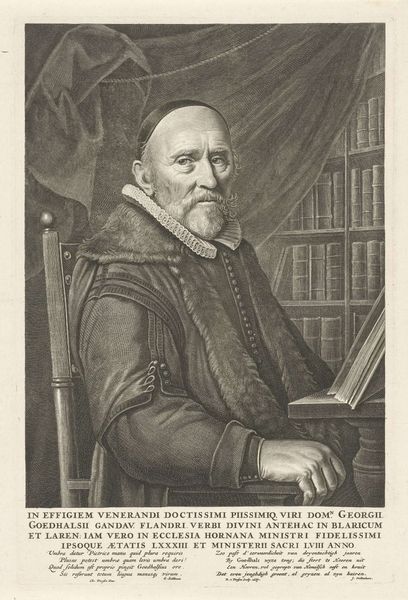

Dimensions: height 301 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

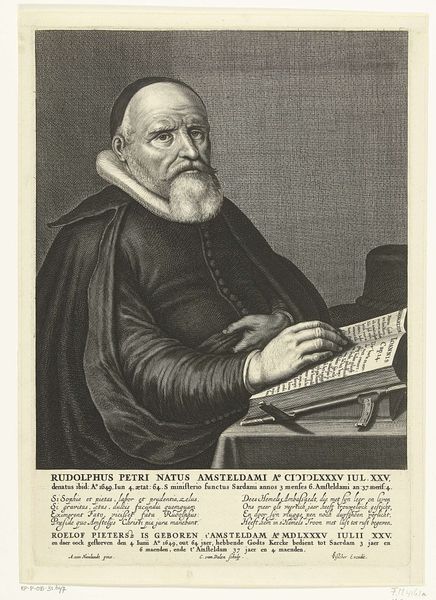

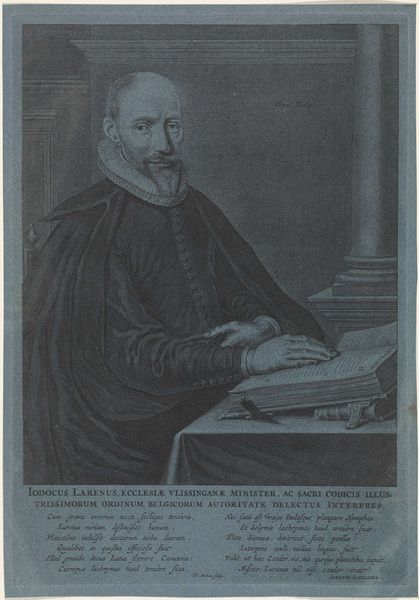

Curator: Here we have a fascinating piece from the Rijksmuseum's collection: "Portret van Rudolphus Petri." It’s an engraving dating back to sometime between 1649 and 1751 and appears to be signed by both H.F. Waterlin and H. Meyer. Editor: My immediate reaction is how meticulously rendered this portrait is. The engraver’s skill in depicting fabric and texture is impressive. You can almost feel the weight of his garments, see the individual hairs in his beard. Curator: Exactly. The clothing immediately denotes a man of stature within the Dutch Golden Age, which resonates with ideas of Dutch Calvinist thought during that time, and his very distinct place within the Dutch Republic’s narrative. Notice the sharp division of light and shadow? The man is brought forward almost heroically. Editor: Yes, the artist uses shadow to emphasize both the opulence and the austerity of the subject. And I'm struck by how the implements of work– the open book, maybe an edition of something, and a pair of scissors– are presented so deliberately. They are almost extensions of Petri himself. It gives weight to how hard people worked and studied. Curator: It’s carefully staged, wouldn't you agree? I can't ignore his gaze looking past us almost. As if pondering his duty. His role not only in Amsterdam but his perceived calling, you could say he almost possesses a world-weariness in those eyes. And his garments reinforce the cultural position that has been placed on him by others as well as society's high expectations. Editor: These were indeed new forms of societal identities and labors starting in the early modern period and being challenged through their representation. He also must maintain his position. Think about the social labor of making paper for example. His clothes must represent all of those who produced that raw material so he may practice in front of an open book. What an interesting social responsibility for clothing, in essence? Curator: Precisely, the print really embodies both individual duty, both moral and spiritual, alongside burgeoning industrial infrastructures which also became part of civic responsibility. The print operates almost like a material contract in this sense. Editor: It is a material record of expanding ideologies. I will think of this material production of a print as representing the expectations of people working hard. Curator: And I'll keep it in my thoughts as embodying what early modern self-reflection means given societal duties.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.