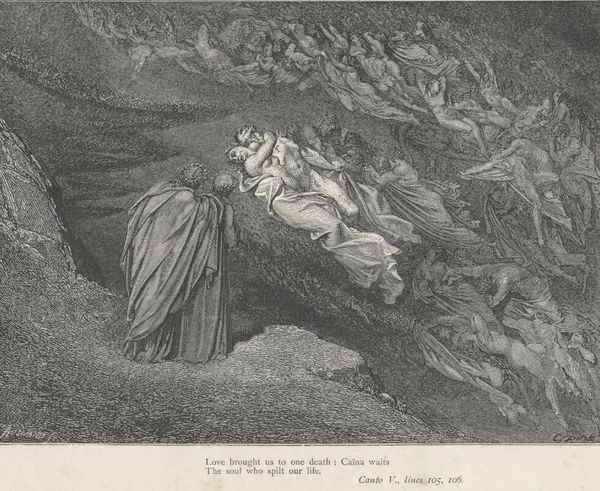

drawing, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

surrealism

#

mythology

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: Public domain

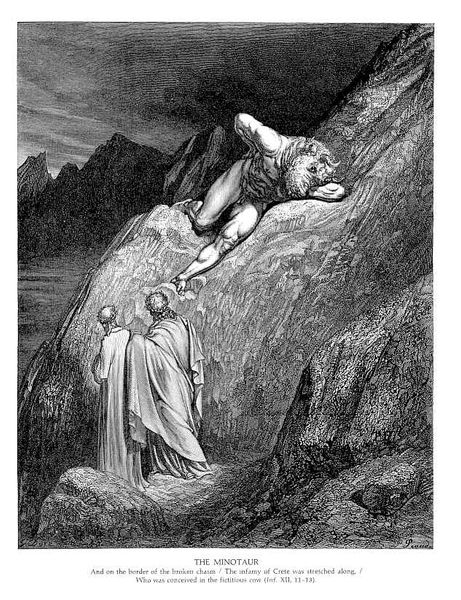

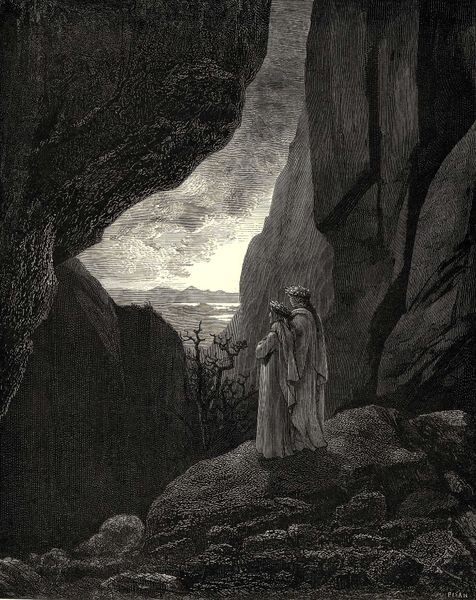

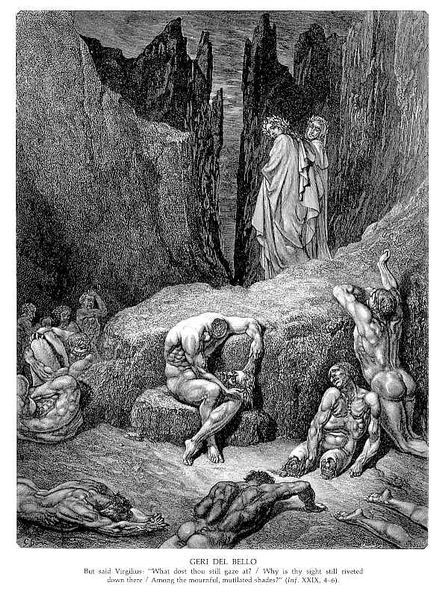

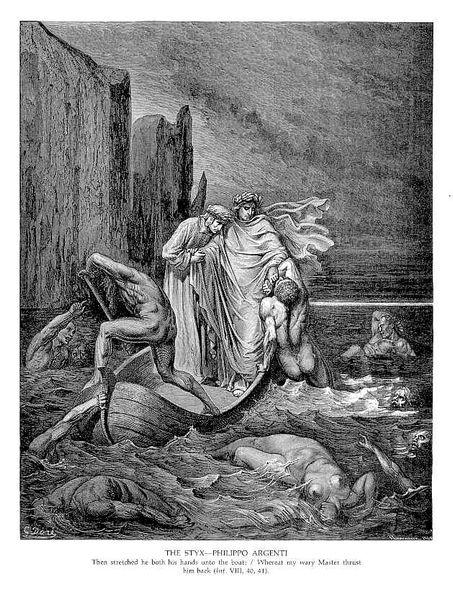

Curator: Let's turn our attention to Gustave Doré's dramatic engraving, "The Inferno, Canto 12." Doré, a master of Romantic illustration, here visualizes a scene from Dante's epic poem. Editor: It's immediately striking – a brutal and imposing landscape dominates. The human figures seem almost dwarfed by the sheer scale of this... rocky abyss, perhaps? There's something deeply unsettling about the light and shadow. Curator: Absolutely. Doré masterfully uses chiaroscuro to amplify the emotional weight. "Canto 12" describes Dante and Virgil's descent into the seventh circle of Hell, guarded by the Minotaur, depicted here, sprawled across the broken landscape after being wounded. It is a physical manifestation of rage and thwarted power. Consider the historical context; the social anxieties around justice, divine and earthly, would have been very real for his audience. Editor: Right. You see that immediately in the raw material expression— the deliberate, physical process of engraving itself mirrors the grueling journey Dante describes. Think about the labor and time invested in creating this single image. It is as if Doré, through his craftsmanship, is literally digging into the darkness of the Inferno. And consider the political aspect: were people experiencing their political struggles as an “inferno” or something akin to that? Curator: Precisely, it serves as both personal and political commentary, reflecting both the societal structures and the moral questions posed by Dante's work. It is the symbolism of the Minotaur, a hybrid creature, tormented and defeated. The creature embodies mankind's beastly nature as much as it presents a societal aberration from an enlightened mind. It is a perfect image of monstrosity but in abject defeat. Editor: I appreciate your point that his portrayal brings in both moral dimensions of humankind. Seeing it, though, also brings to mind questions of accessibility and production – engraving allowed for the relatively widespread distribution of these images. So, it goes beyond "high art." What kind of access would a broader public, experiencing harsh socio-economic conditions, had with these sorts of representations of the powerful and wretched? Curator: Good question, considering its dissemination. By making it accessible, the piece allowed many to interrogate ideas of power and torment. Its continuous social impact is an important factor to discuss as we close our brief viewing of Doré’s terrifying, but masterful "Inferno." Editor: Indeed. Seeing it not as simply art, but labor materialized in cultural production is also, for me, a great takeaway from our short engagement here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.