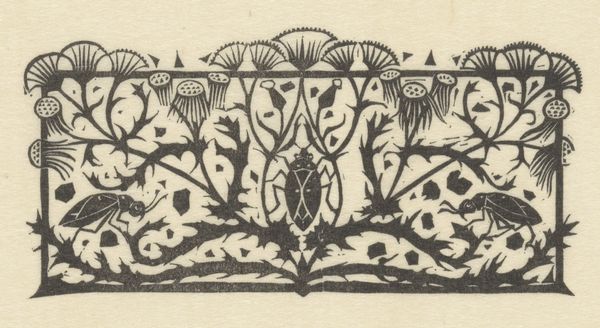

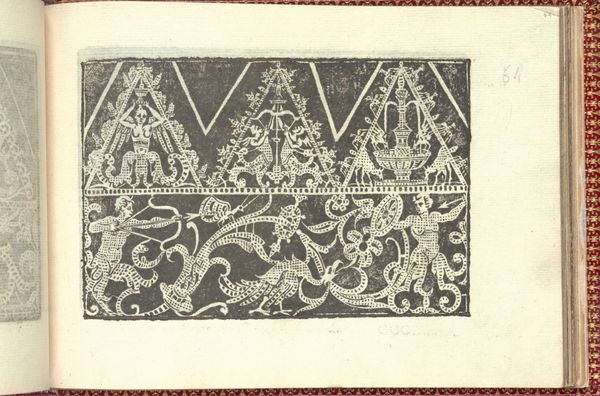

Titelhoofd met mannen die druiventrossen dragen 1893 - 1927

0:00

0:00

gerritwillemdijsselhof

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, woodcut

#

graphic-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink line art

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

woodcut

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

doodle art

Dimensions: height 64 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Dijsselhof's "Titelhoofd met mannen die druiventrossen dragen," created sometime between 1893 and 1927, is a compelling woodcut, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. I'm curious about your initial reading of the work. Editor: My immediate reaction is to its strong graphic quality. The stark contrast of black and white and the bold outlines give it a decorative, almost heraldic feel. Curator: Indeed. Beyond its aesthetic qualities, let’s consider the broader narrative at play here. The figures bearing grapes aren’t merely decorative. Grape harvesting has historically been tied to celebrations of communal work and seasonal changes. In colonial contexts, wine became entangled in the politics of power and trade. What might it signal here? Editor: That's a compelling question. From a formal perspective, I'm struck by the patterned surfaces and the repetition of shapes. Look at how the leaves and grapes are stylized and arranged; it creates a very rhythmic composition. It moves your eye across the surface in a pleasing way. The stylized approach is echoed by the silhouette work on the central figures and leaves. Curator: Right. The simplification of form invites deeper consideration. Who were these men? Did their labor directly benefit from the fruits they carried, or were they subject to larger socio-economic forces? The figure on the left carries his grapes; the one on the right seemingly gestures, trailed by a canine. Perhaps that denotes some aspect of ownership, contrasting enslaved versus hired labor. The question then is whether that represents Dijsselhof's social view of such structures at the time. Editor: I see what you're saying, and that's important. But I think it's crucial to consider how the graphic nature of the work impacts its message. The patterns and rhythms create a celebratory effect, despite any tension of the central subject matter. It could, also, reference an idealized vision of labor, a carefully constructed artistic vision that smooths over these tougher realities. Curator: Certainly. It's a fascinating ambiguity, isn't it? This tension between a polished aesthetic and the embedded questions of historical social strata seems characteristic of that period, in many ways mirroring that which exists today. It definitely complicates any singular reading. Editor: Yes, precisely! Seeing this as a representation and not just a construction truly deepens our understanding of Dijsselhof’s skill and historical place. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.