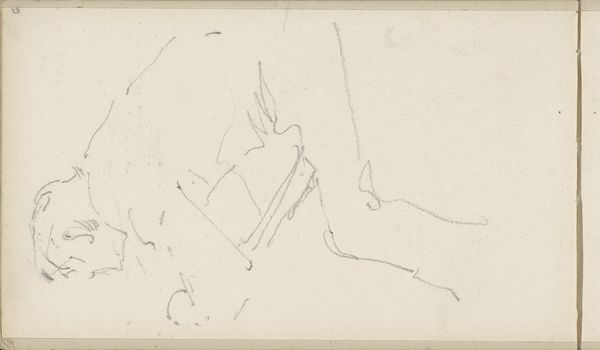

drawing, paper, dry-media, graphite

#

drawing

#

paper

#

dry-media

#

abstraction

#

line

#

graphite

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

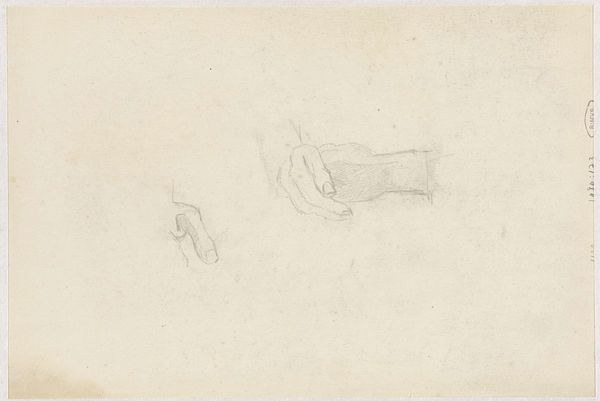

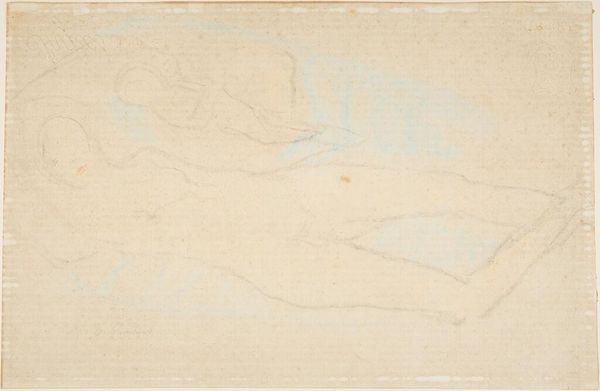

Curator: Here we have "Studie" by Bramine Hubrecht, created sometime between 1865 and 1913. It’s a drawing on paper using graphite. It now resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is one of almost ethereal lightness. The delicate lines barely there against the paper; it feels incredibly fragile, a fleeting thought captured. Curator: It's tempting to see it as merely unfinished, but what about the labour invested in making it, transporting it, and now preserving it? Graphite, as a readily available material, democratized art-making; how does its use here challenge notions of preciousness in art? Editor: The interplay of line and void is compelling. Those swirling shapes, though indeterminate, create a palpable sense of movement and depth. Notice how the artist varies the pressure on the graphite, lending nuance and a subtle rhythm. Semiotically, it prompts a sense of absence and creation. Curator: But isn’t the semiotic approach divorced from its socio-economic reality? What of the paper's provenance, the means of producing the graphite itself? These considerations root the piece within a specific time, a moment of burgeoning industrialization that altered access to and means of making art for women like Hubrecht. Editor: I disagree—by emphasizing the material origins of an artwork you could risk erasing artistic intent, focusing too much on external production rather than considering the intentional construction of its forms and themes. I would propose instead looking closely at the tension held in those near-invisible lines... Curator: The choice to work in graphite allowed a proliferation of art outside the traditionally elite. Focusing on its manufacture and accessibility enables us to reclaim "craft" as intellectual labor. And ultimately understand the historical democratization of art. Editor: A compelling argument for sure. Ultimately, appreciating "Studie" comes from recognizing this artwork’s ability to exist as something unresolved, even ambiguous. It demands attention and allows space for individual contemplation. Curator: Precisely. And situating that space within the context of material production allows us to see that so-called ‘abstraction’ isn’t divorced from reality. The production informs the aesthetics, even defines the emotional impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.