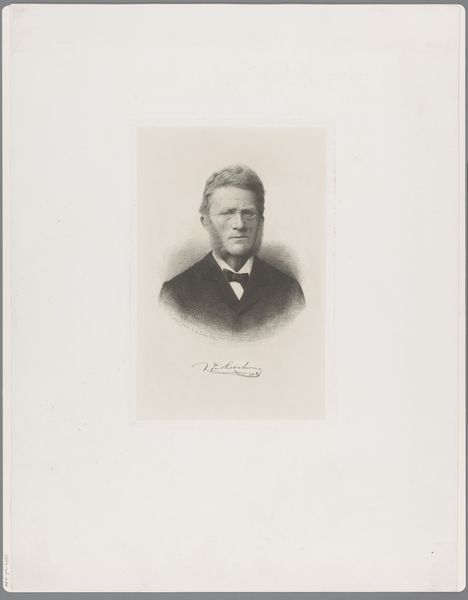

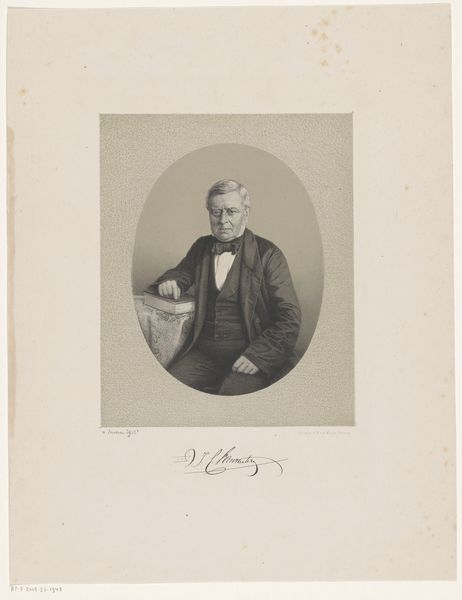

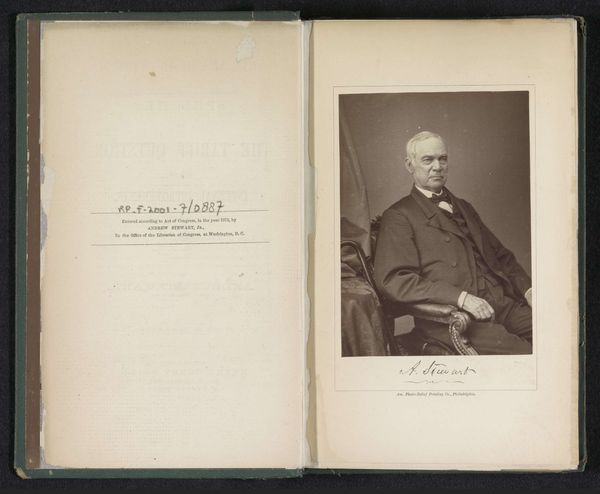

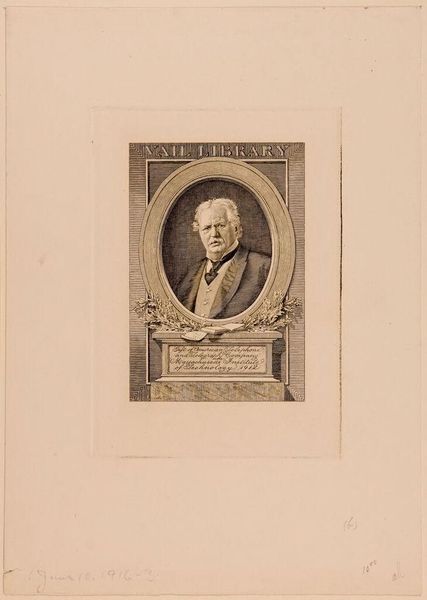

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

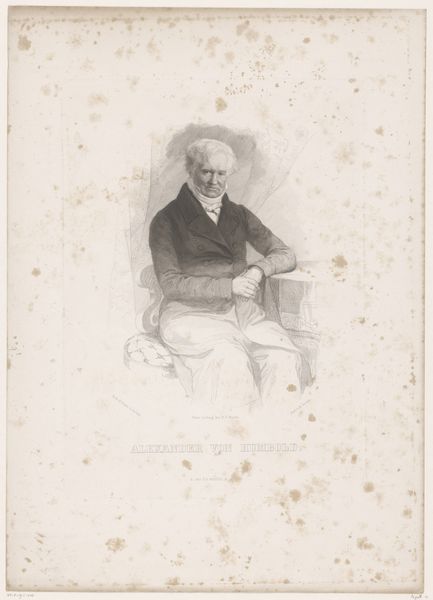

aged paper

#

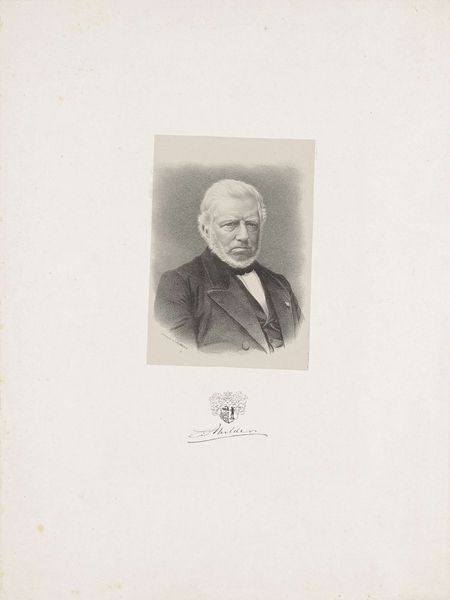

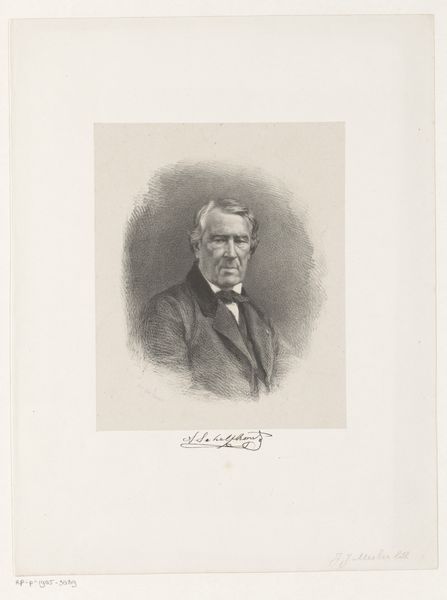

script typography

#

old engraving style

#

hand drawn type

#

personal journal design

#

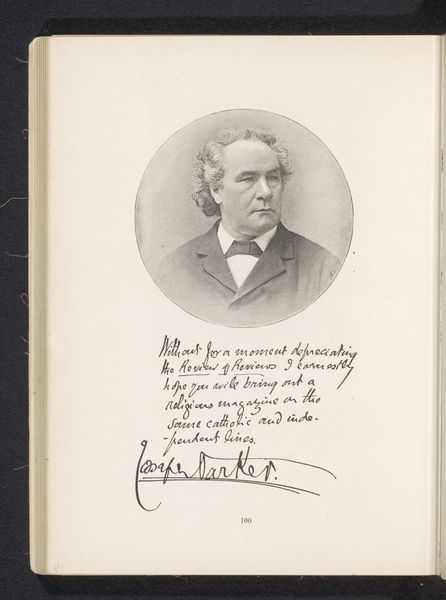

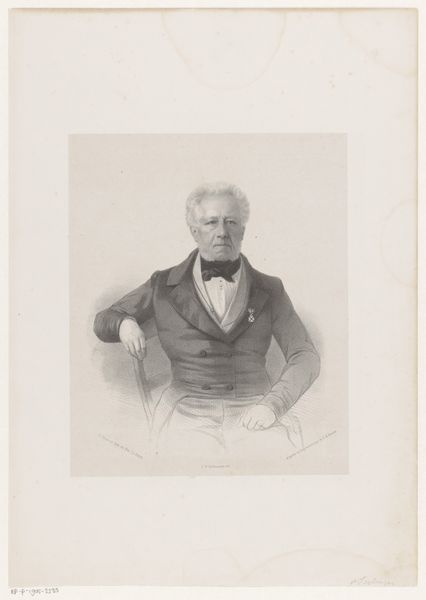

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

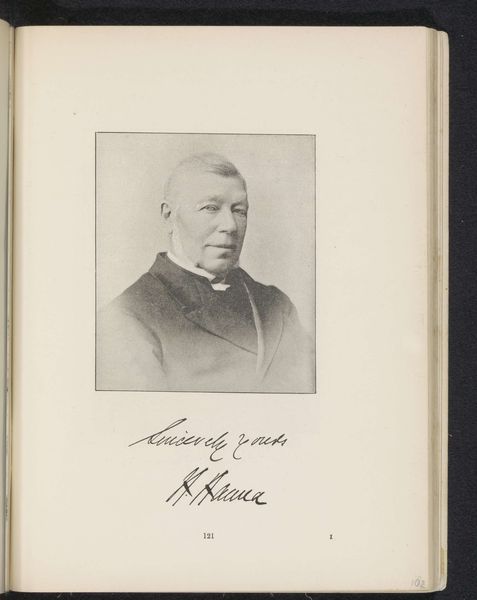

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 82 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Portrait of Ivan Vyshnegradsky," it's listed as being created before 1891, and the medium is albumen print. What strikes me is how it looks like it’s been pasted into what might be a personal journal or sketchbook, along with some handwriting. How does this format affect your interpretation? Curator: It is quite interesting, isn't it? The albumen print, a very common photographic process in the 19th century, is presented here within the intimate context of a personal journal. This speaks volumes about the role of photography at that time. Consider that prior to photographic reproduction, portraits were the domain of the wealthy. But photography democratized portraiture and became integrated into daily life, almost like snapshots today. Editor: That's a good point, especially seeing it paired with a handwritten note, it almost feels like an early form of a letter with a photograph included. Did people treat photographs as precious or archival at the time, even as accessibility increased? Curator: Exactly! While photography was becoming more accessible, each image still carried a certain weight. Archiving practices were evolving. Early photographs were often considered important records of people and events, far more so than mere ephemera. So its presence in this book, along with text referencing sending "statistics" suggests Vyshnegradsky held an important professional role and the portrait served as part of recordkeeping and networking. Editor: The handwritten note seems to corroborate that it's referencing sending documentation somewhere, and that this image has something to do with his role. So seeing the photograph and the text together… it tells a broader story, something more than just a visual representation. Curator: Precisely. We can consider this object as evidence of the public role photography quickly assumed within the shifting political landscape of image-making in the late 19th century. Editor: That makes so much more sense. I initially saw it as a simple portrait, but it’s really tied to history and how information and image sharing was evolving. Curator: Absolutely. It's a powerful reminder that art and historical context are inseparable.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.