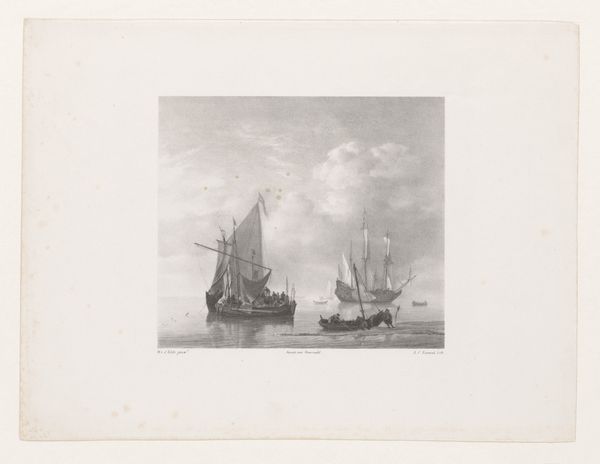

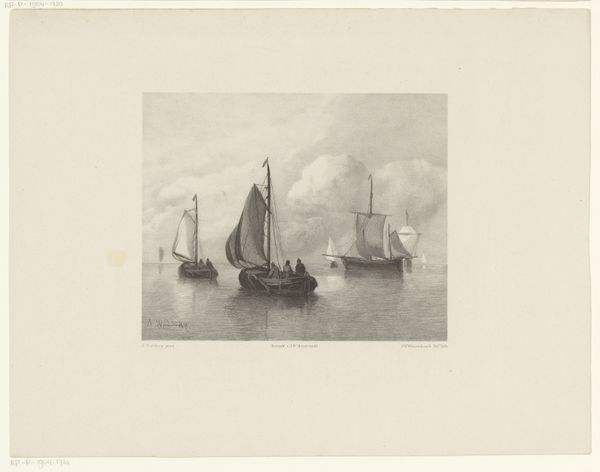

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 356 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

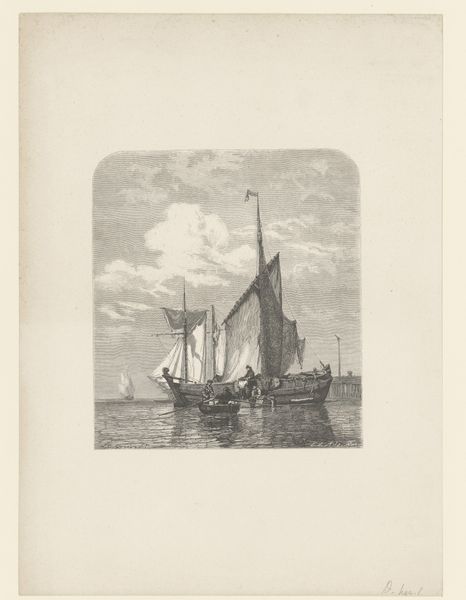

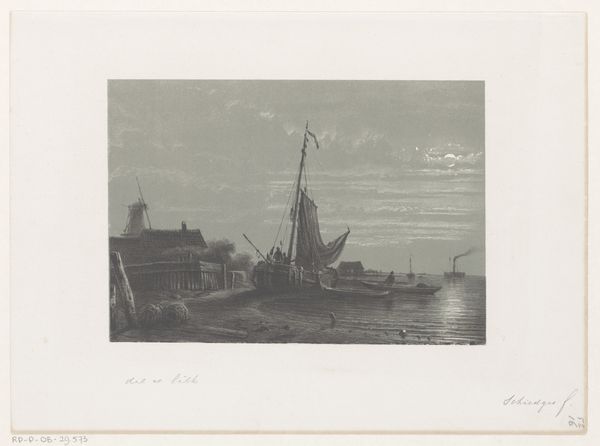

Curator: Looking at Adolf Carel Nunnink’s etching, "Zeilboten op Theems bij Londen" from 1859 to 1865, one is immediately struck by the intricacy achieved in print. What's your take on it? Editor: There’s a certain melancholy to it, don't you think? The misty Thames, the towering sailing boats—it evokes a sense of the industrial age pressing in, a sort of liminal space. Curator: Indeed. The piece is an etching, meaning Nunnink painstakingly used acid to bite lines into a metal plate, showcasing precision but also physical labor to transfer onto paper, creating a consumable scene of London. Editor: Right, but it's more than just a scene. Think of the Thames itself, a historical artery of empire. This etching, produced during a period of intense colonial expansion, offers a glimpse into the heart of that economic and political power. The sailboats become symbols, perhaps, of both trade and the exploitation inherent within it. Curator: Absolutely, though one could also see the sailing vessels more practically. As functional craft integral to the Thames’ economic ecosystem—ferrying goods and people through the bustling port, a literal vehicle for commercial labor, made with materials sourced through trade and likely built in local shipyards. Editor: True, but consider also who has access to these waterways and the goods they carry. This idyllic image likely obscures the harsh realities faced by the working class reliant on this very industry for survival. Curator: Still, the craft! The sheer skill involved in the etching process… The layering, the manipulation of light and shadow… It transforms something potentially quotidian into art intended for consumption, accessible now to a broader audience via the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: And how is that accessibility shaped by class, race, gender? Whose perspectives are amplified by such institutions? This artwork provides not just aesthetic appeal, but a vital entry point for engaging with broader systemic issues about social injustice within systems of global power and production. Curator: I concede, there's always more to the image, a need for deeper reading. Nunnink’s work offers insights into the technologies of art-making as well as the context from whence they emerged. Editor: Precisely. By grappling with the social and historical currents, we can approach not only visual analyses, but promote collective learning, encouraging us to reassess present challenges.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.