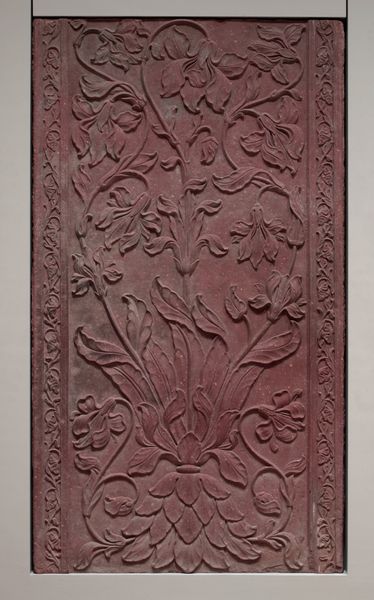

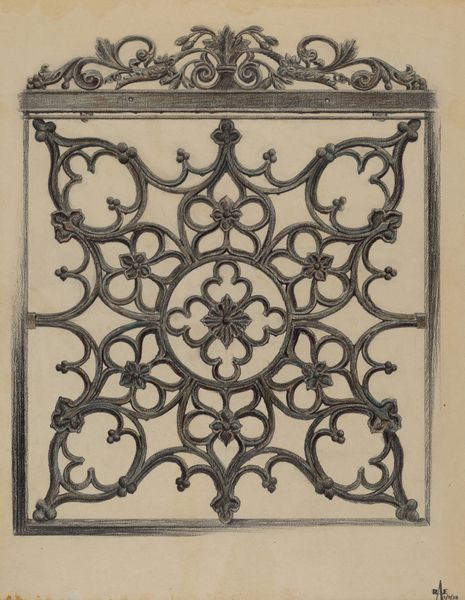

Schlesinger and Mayer Company Store, Chicago, Illinois, Baluster 1898 - 1899

0:00

0:00

metal, sculpture, architecture

#

art-nouveau

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

form

#

sculpture

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: 89 × 25 × 5 cm (35 × 10 × 2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Today, we're looking at a baluster created by Louis Sullivan between 1898 and 1899 for the Schlesinger and Mayer Company Store in Chicago. It's now housed here at the Art Institute. Editor: My first impression is one of intricate detail – almost lace-like despite being constructed from metal. There’s a clear emphasis on the craftsmanship involved. Curator: Absolutely. And the context is critical. Sullivan's work on the Schlesinger and Mayer building, later known as Carson Pirie Scott, was revolutionary. This baluster exemplifies his organic ornamentation. But think about the social implications. It adorns a department store, a site deeply interwoven with gender roles, consumerism, and the burgeoning role of women in the public sphere at the turn of the century. Editor: And you see how this blends into the context of metalwork production. The material itself, likely cast iron, and the methods used to create such complexity are central. How did the workers producing these feel contributing to this vision? The object embodies their skill and the labour process is key to my appreciation of this beautiful detail. Curator: The design also breaks from traditional architectural forms, embracing the Art Nouveau style, a conscious effort to create a distinctly modern, even American, aesthetic. The curved lines, the floral motifs—they speak to a desire for a new kind of beauty, rejecting the Beaux-Arts classicism that dominated architectural education at the time. Consider that alongside the building's function; a public and commercial enterprise accessible to all – there are questions of access and societal transformation. Editor: Sullivan merged form and function here. Mass production techniques meant his elaborate vision was reproducible at scale. These adornments became almost ubiquitous; democratic because of the machine and this makes an impact as this accessibility was also a design objective in my mind. Curator: The use of ornamentation becomes not just decorative, but expressive of democratic ideals within the new possibilities of capitalism. Considering whose ideals were made visible remains the key here for me. Editor: Exactly. It’s crucial to explore how materials and manufacturing democratized art while obscuring worker exploitation. Curator: Thank you. The way the metal material and design converge with broader questions is striking to think about even now. Editor: Precisely! Examining the design, labor and reception unearths some new things still, I suspect.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.