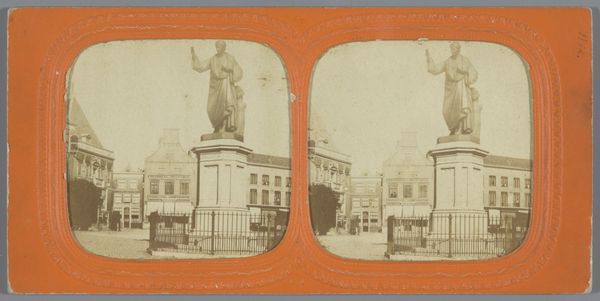

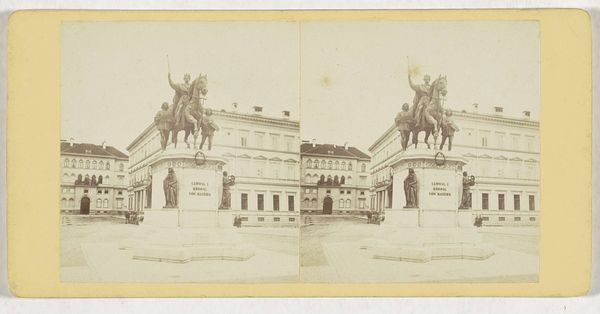

Gezicht op het standbeeld van Godfried van Bouillon met daarachter de Hofbergstraat en de toren van het stadhuis in Brussel 1861 - 1870

0:00

0:00

bt

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

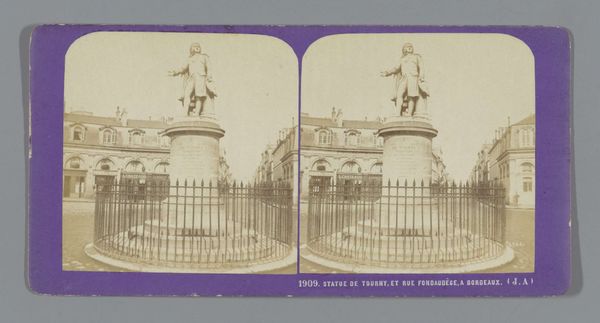

Curator: Look at this intriguing cityscape, “Gezicht op het standbeeld van Godfried van Bouillon…”—or "View of the Statue of Godfrey of Bouillon"—taken between 1861 and 1870. It’s housed here at the Rijksmuseum. What catches your eye first? Editor: It has a sort of melancholic atmosphere. Everything's steeped in this hazy sepia tone. Like peering through a very old dream, of a place just beyond reach. Curator: Indeed, the photographic process of the era certainly contributes to that. We see here a convergence of city planning, photographic technology, and the business of image distribution. The rise of the city necessitates images of its progress, creating this kind of picturesque view of civic pride, captured through the then-novel medium of photography. Editor: Absolutely. And that statue! Godfrey, raised high with his waving flag, presiding over his city. It's an image of power, no question, but look how diminutive the people appear around it! The sculptor’s craft elevates history and then photography reproduces it, both processes shaping public opinion. It’s interesting that the scene also offers a candid representation of folks on the street as passersby—it introduces questions about commerce, access, and who exactly are monuments like these created for? Curator: Good point! Considering that this photograph, meant for distribution, presents not only a constructed ideal but a depiction of daily labor and life occurring around the sculpture. Look closely. This interplay is a testament to photography's dual role: to celebrate but also to document the social and economic context in which monuments exist. Editor: I also like how it manages to capture both the grandness of the city's architecture and these ordinary human details, people almost swallowed by the city itself. This photo reminds us how quickly what is meant to represent permanence morphs, changing how these emblems come to represent values—especially today. Curator: Ultimately, this view connects the material conditions of urban development with our perceptions of history and national identity—as seen through a lens manufactured, distributed, and consumed widely. Editor: A potent snapshot that still resonates so strongly—a melancholy beauty, preserved in sepia tones and sharp lines.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.