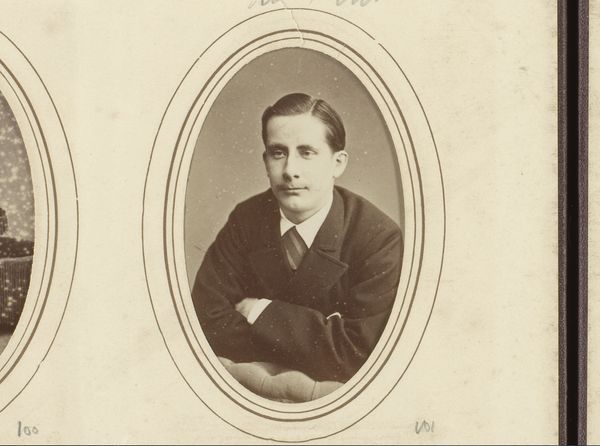

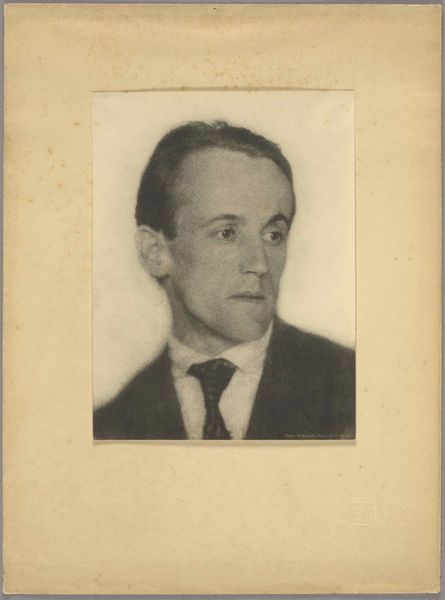

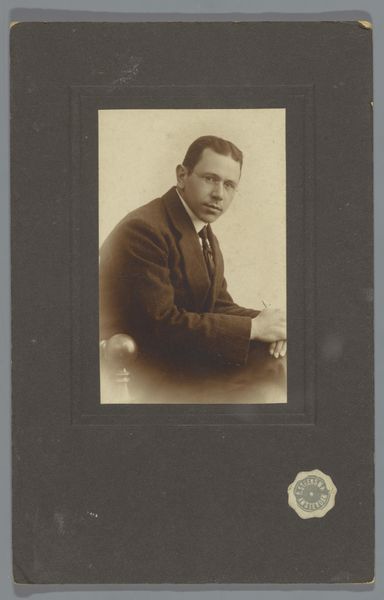

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

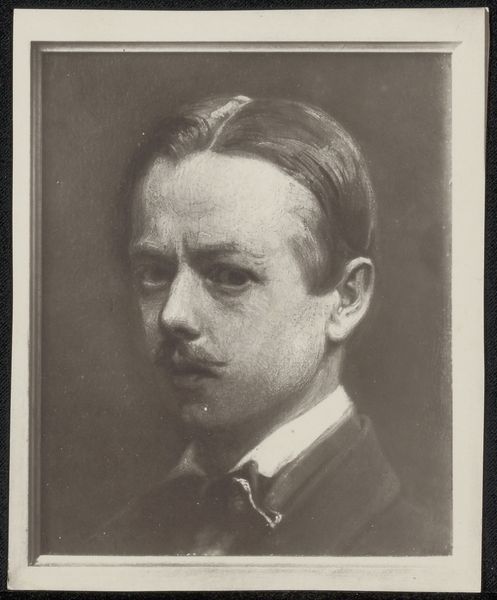

charcoal drawing

#

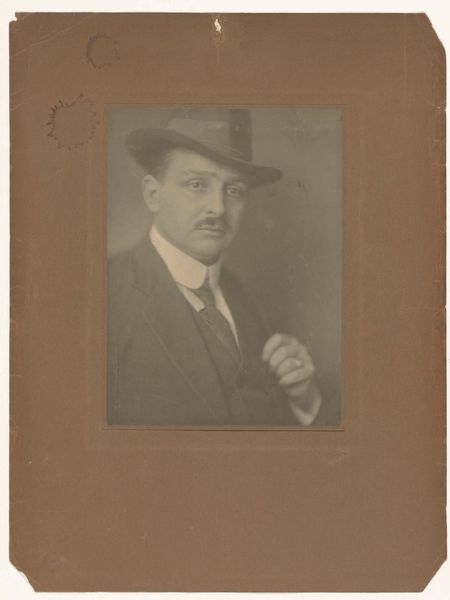

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin silver print, simply titled "Portret van Johannes van Zijll de Jong," dates from between 1930 and 1935. There's an intimacy about it, don’t you think? Editor: It's a very contained kind of intimacy. Almost…restrained. The oval frame-within-a-frame adds to that sense. You immediately think about how this would have been displayed in a private space, consumed within a certain social structure of seeing. Curator: Precisely! I sense a deep well of interiority in this man's eyes. It is more than a photograph, really, I feel like it reflects a yearning, a sort of modernist search for meaning. Does it move you, inspire thought, or just reflect life in times gone by? Editor: I am struck more by the mechanics of how it was made, the materials that are now slowly deteriorating on a molecular level – and who was involved in its creation and commissioning. Did this sitter participate in this photographic process, or was he just a mere object? These are the more urgent questions I am trying to understand about an object like this one. I'm fascinated by the intersection of realism and modernism happening at this point in history. What a pivotal moment to take one’s portrait. Curator: Indeed! But there is also something timeless about that face, something universally human. Do you think photography, despite its documentary qualities, can still possess a certain poetic license? Almost that anything rendered visually bears the creative or perhaps biased lens of those looking back on the piece. I just imagine him full of thoughts, living in his quiet way, maybe wondering about the very questions that occupy us now. Editor: Well, the choice of gelatin silver print is definitely important; by the 1930s, this was an established, almost standard process, widely used due to its relative stability and affordability. Consider how that choice democratized portraiture, offering a broader segment of society a way to record and preserve their image. Curator: So in a way it speaks to democratization? Maybe it also embodies the desire to elevate one’s self through image-making? Well, regardless, it definitely gets under my skin. Editor: Absolutely. Looking beyond the aesthetics gets one pondering larger social dynamics, like how photographic processes impact labor and material culture. It makes this a useful historical object as well as artistic document, even when considering its current condition of conservation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.