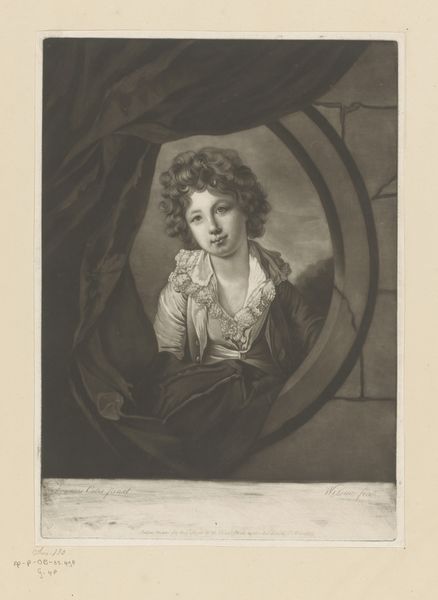

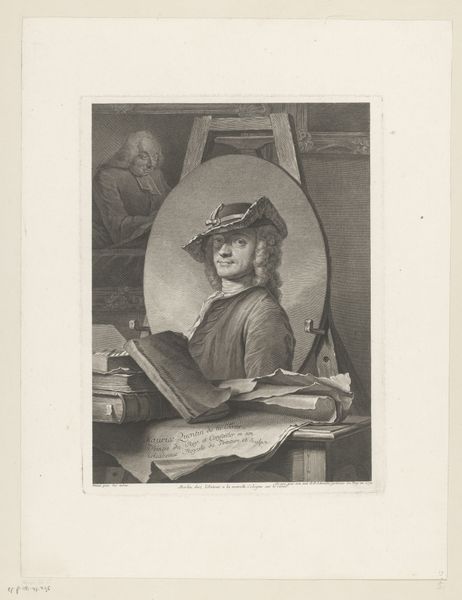

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

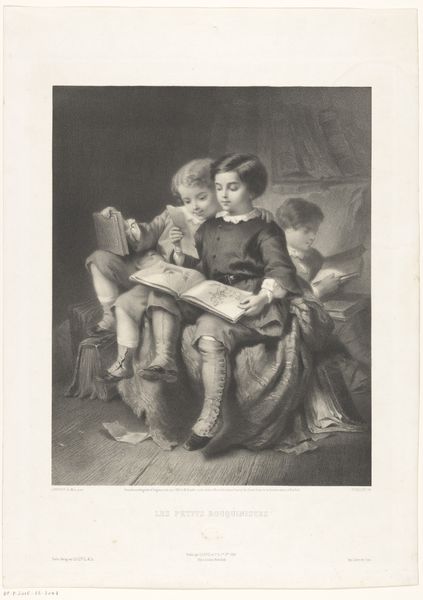

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 387 mm, width 289 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

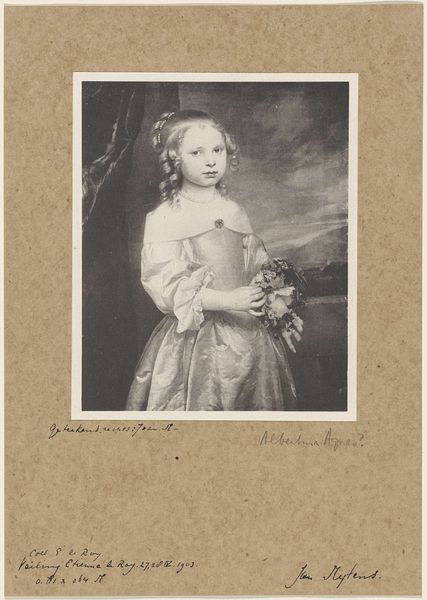

Editor: So, this is “Portrait of Helena Beatson as a Child,” an engraving from 1768 by James Watson. She looks like she's having a good time drawing. It’s pretty amazing to think about how this image was made by hand, carefully cutting into a plate. What do you think of the engraving from a materialist perspective? Curator: It’s fascinating when you consider the labour involved. Watson, like other engravers, was essentially part of a reproduction industry. The copperplate engraving allowed for multiple, relatively affordable copies of paintings to be circulated. Consider this: Watson was not just making "art" but also producing a commodity. The labor invested in this specific process, creating these lines, how they translate this scene from paint into printed image. Editor: That makes a lot of sense. So, it was kind of like a print shop back then, trying to share images with a wider audience? Curator: Exactly. And who could afford these prints? The rising middle class. These objects became markers of taste and social aspiration. Think about the materials as social signifiers – the paper, the ink, the clothing worn by Helena. Even the turban! It all speaks to a complex network of trade and consumption. How do you think this impacts the perception of the work itself? Editor: It’s no longer just a charming portrait, but also a historical artifact of production, class and taste. Viewing it this way adds new significance! Curator: Precisely. It shifts the focus from solely aesthetic value to understanding the conditions of its creation and consumption. Editor: I’ve learned to appreciate these engravings in a new way. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.