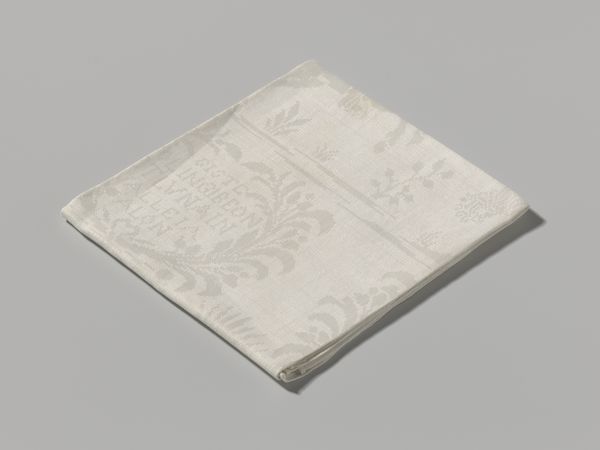

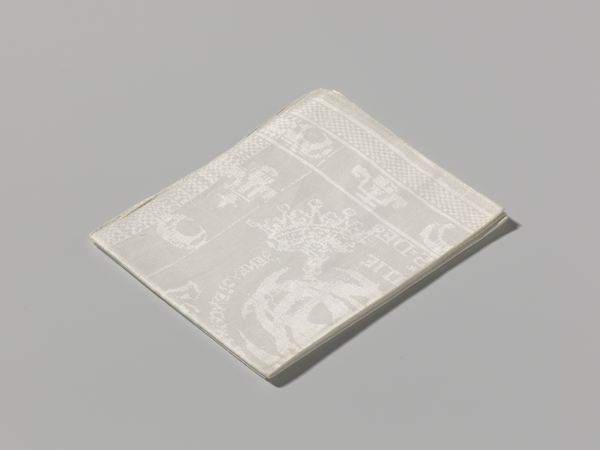

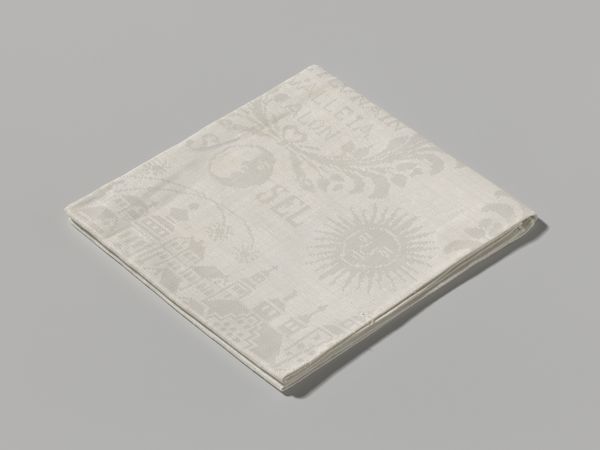

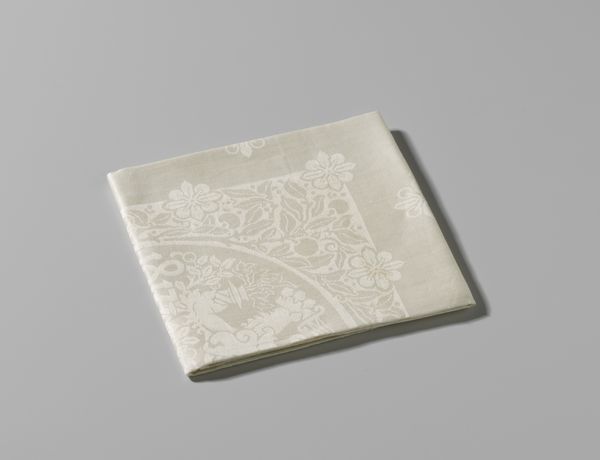

Servet met de verovering van Boedapest door Leopold I, keizer van Duitsland after 1686

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, paper, engraving

#

paper non-digital material

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 110 cm, width 90 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an engraving from after 1686, titled "Servet met de verovering van Boedapest door Leopold I, keizer van Duitsland"—or, "Napkin with the conquest of Budapest by Leopold I, Emperor of Germany". It’s printed on paper, and you can see that it’s a functional object—a napkin. What’s interesting is the seeming mundanity of this object celebrating such a historically important event, and it makes me wonder why history would be celebrated in such a daily-use format. How do you interpret this piece? Curator: The choice of a napkin as a medium is incredibly telling. It brings the grand narrative of Leopold I’s victory directly into the domestic sphere. Think about the social context: dining was, and still is, a highly social and performative ritual, especially for the elite. Editor: So, it’s about bringing political power into a domestic context? Curator: Precisely. This napkin isn't just functional; it’s a propaganda tool, subtly reinforcing Leopold’s authority during every meal. The Baroque period thrived on spectacles of power. Commemorating victory, like this conquest, on everyday objects integrated these victories into the fabric of daily life, normalizing and celebrating imperial power. Where do you think these napkins would have been used? Editor: Ah, probably high-status banquets and celebrations—events carefully curated to impress and maintain the social hierarchy. I hadn't considered it as a form of propaganda before. Curator: Exactly! And remember, art like this served a public role beyond mere aesthetics; it helped shape political opinions and maintain social order. It definitely broadens how we look at art history. Editor: It's amazing how something as simple as a napkin can reveal so much about the political and social climate of the time. I’ll definitely be paying closer attention to the objects surrounding artworks from now on!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.