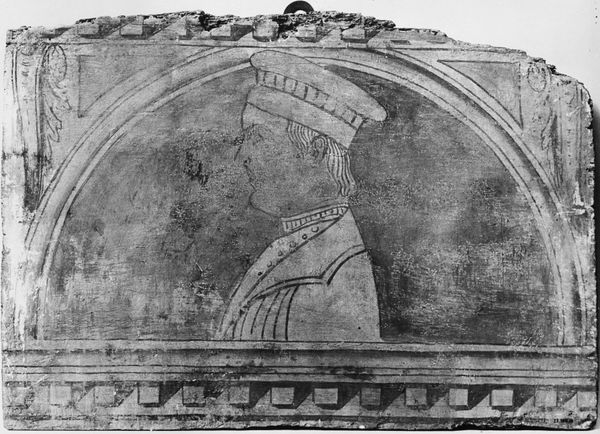

painting, fresco, sculpture

#

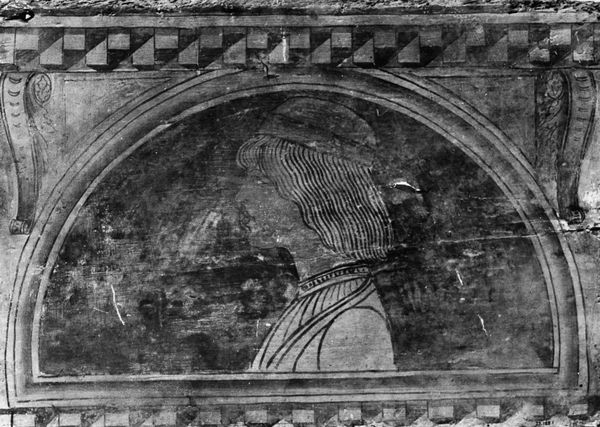

portrait

#

painting

#

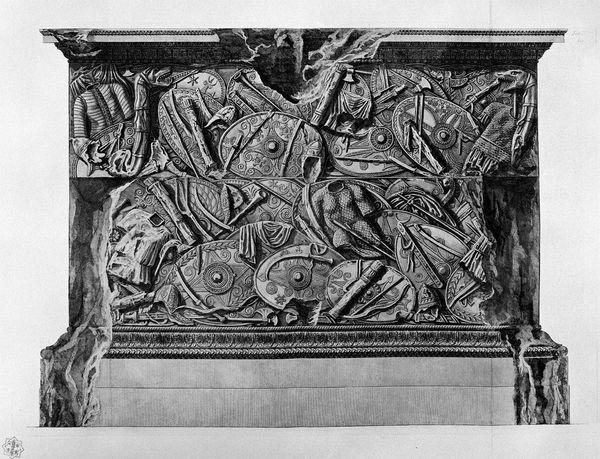

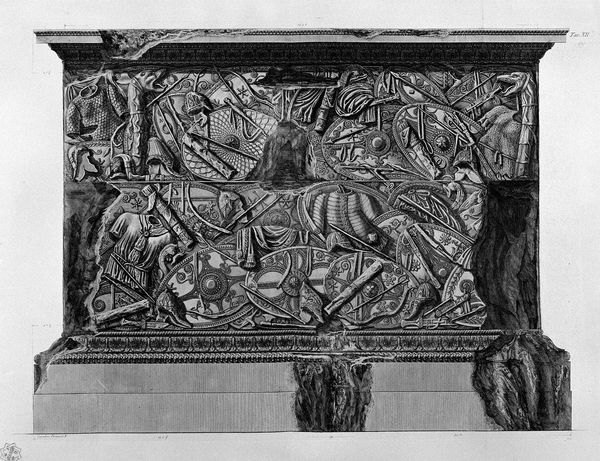

sculpture

#

fresco

#

sculpture

#

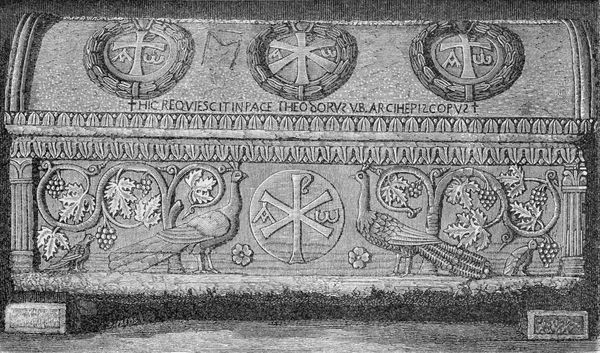

decorative-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

early-renaissance

#

profile

Dimensions: Overall: 16 1/2 × 20 1/2 in. (41.9 × 52.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have what's called "Head of a Man," a fresco fragment attributed to an anonymous artist working sometime between 1485 and 1499 during the Italian Renaissance. Editor: My first thought is the stark profile view; it immediately calls to mind classical sculpture, and the monochrome tones enhance the feeling of ancient authority. But also, there's a striking stillness that speaks to the subject's, presumably a nobleman, detachment from the common world. Curator: The fresco technique, painting directly onto plaster, was incredibly popular at the time for its durability, aligning with the Renaissance desire for legacy and permanence. Consider, too, how these profile portraits often functioned within complex social systems of power and patronage. What was he communicating? What position does this signify? Editor: Absolutely, we must acknowledge that profile portraits often served a propaganda purpose for solidifying the family name or displaying power within Italian courts. It would be very intriguing to uncover more information about its original display location. Frescos were obviously site-specific, suggesting a particular political or social message conveyed to its initial audience. He’s certainly posed with cool reserve; is it arrogance or simply controlled self-presentation? Curator: Examining Renaissance society, this type of image helped establish elite identity. But also, think about its current setting within a museum; its display is completely divorced from its intended purpose, isn't it? What implications arise as it transitions to an artwork rather than a functional visual statement? Editor: A crucial point, because exhibiting it in the Metropolitan Museum of Art allows us, now, to analyze it within conversations of gender, representation, and political power far exceeding that initial message intended at its creation. Did he sit in power in a violent, sexist, or otherwise prejudiced system? We should challenge that narrative if we can. Curator: Very well said. These shifts in context allow us to rethink our role in looking at and historicizing a given object. It no longer acts only as an individual man’s portrait but transforms into an indexical marker for complex themes of identity, authority, and socio-historical analysis. Editor: Ultimately, it reveals as much about the world that created the image as about the person it portrays, so these contextual refractions enrich our reading.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.