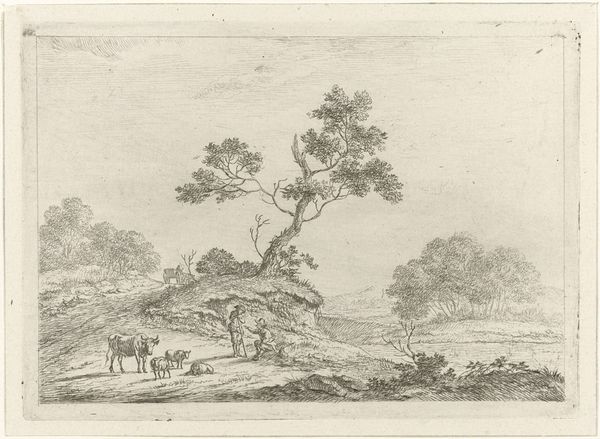

print, etching

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

realism

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This etching, "Herder met drie koeien," by Hermanus Fock, from around 1781-1822, shows a shepherd with three cows near a river or lake. The detail achieved through line work is striking. What can you tell me about it? Curator: What interests me most here is the labor represented in the image – not just that of the shepherd, but also, and perhaps more interestingly, that embedded in the very production of the print. Consider the etcher's hand, the acids used to bite into the metal plate, and the press itself. This print isn’t simply depicting rural labor; it embodies a different kind of work altogether. Editor: That's fascinating! So you're seeing the act of making the print as part of the artwork's meaning itself, reflecting other sorts of labour? Curator: Precisely. The delicate lines you admire were produced through a calculated process of acid erosion, controlled by the artist. And this etching, reproducible, and relatively inexpensive compared to painting, opened art to a wider market and audience. Were there more possibilities that arise from the art piece itself becoming reproducible and accessible to the working class? Editor: I hadn't thought about the economics of printmaking before. Did the art world or working class perceive them to be less prestigious than unique artworks? Curator: Often, yes. But, these prints also democratized art in some ways and celebrated working class life. So in the end, were those realistic style images aimed to highlight class struggles or embrace art democratization and consumerism for new audiences? Editor: It's definitely a new angle for me to consider landscape through a materialist lens. Thanks for opening my eyes. Curator: Indeed. By attending to the materiality and processes of artmaking, we gain richer insight into the art's historical and social context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.