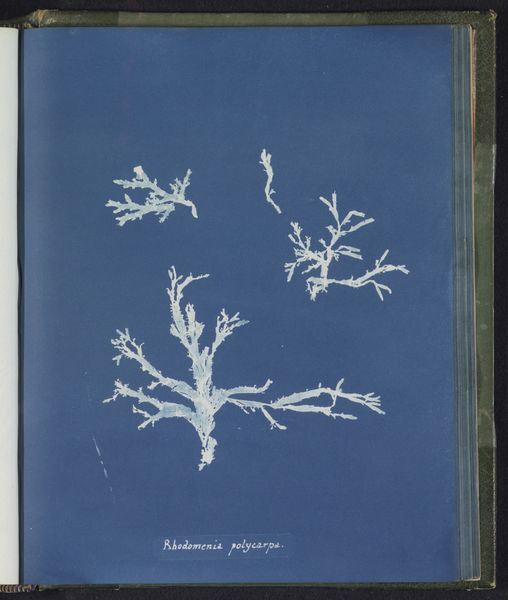

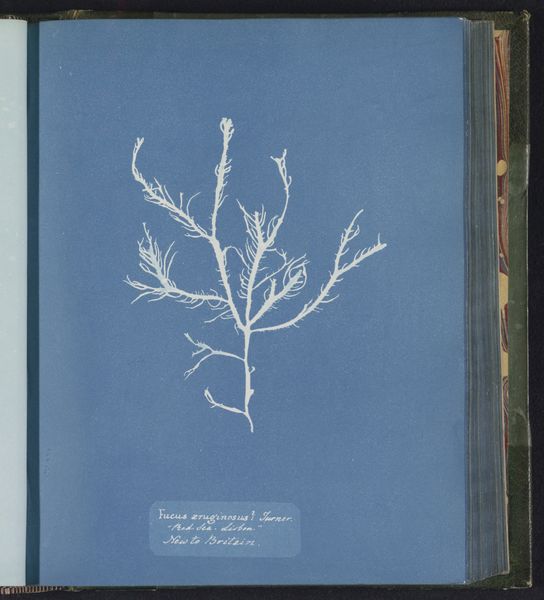

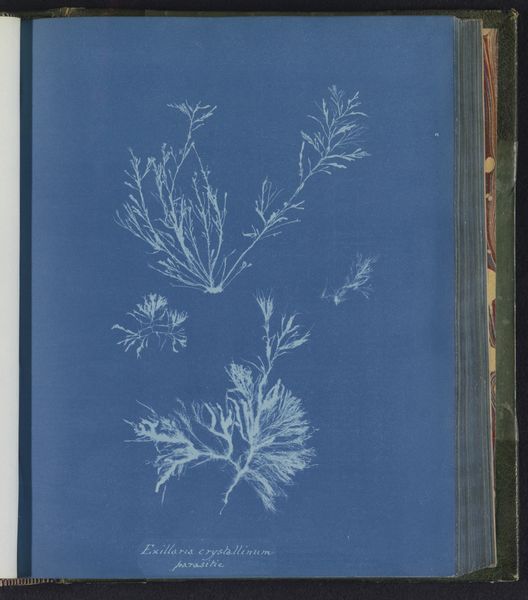

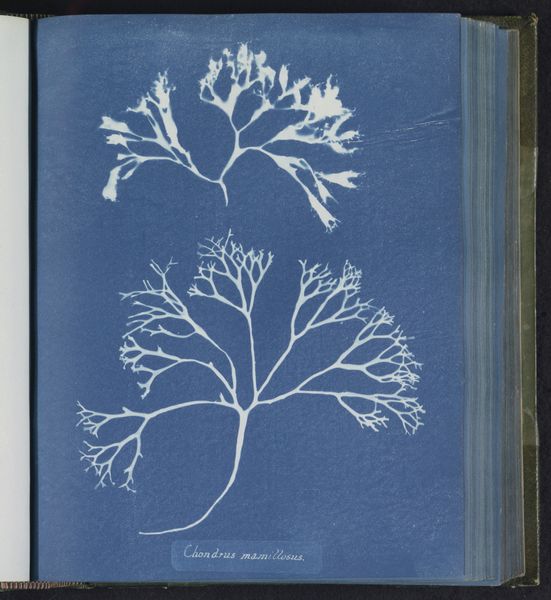

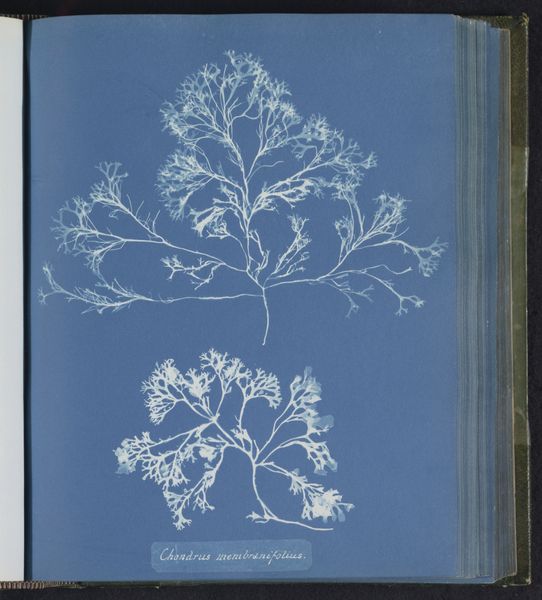

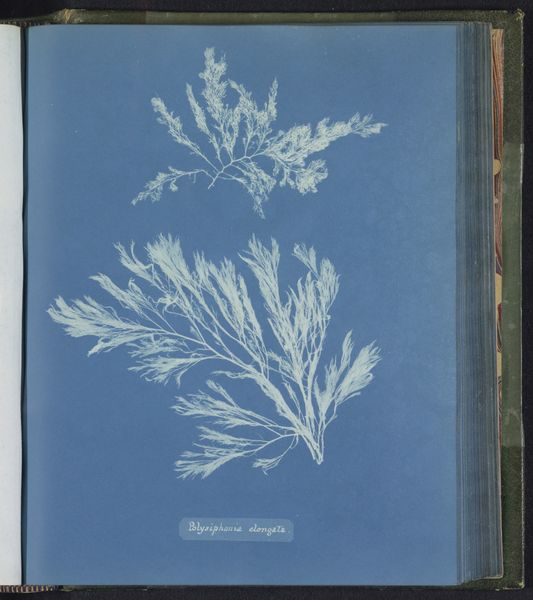

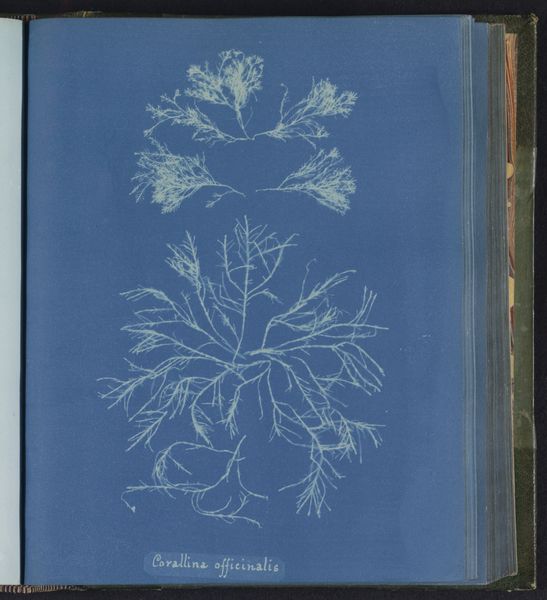

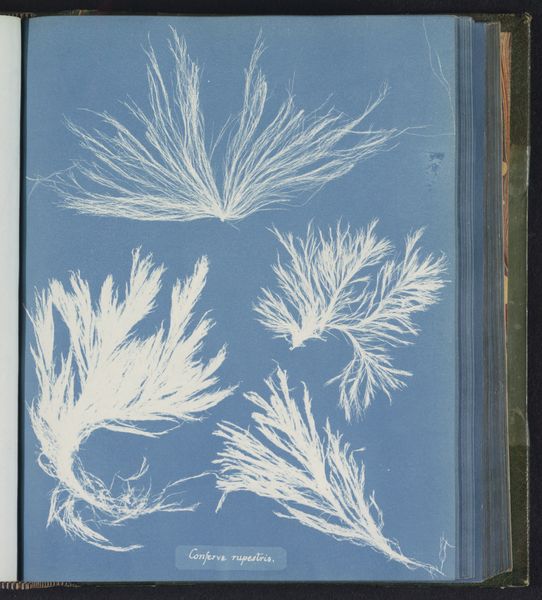

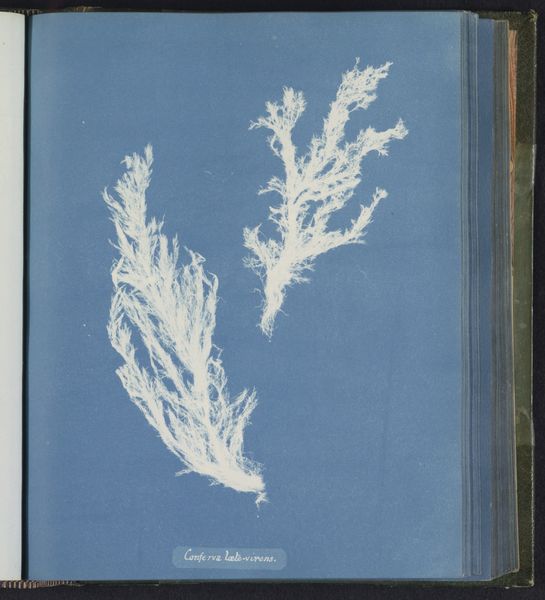

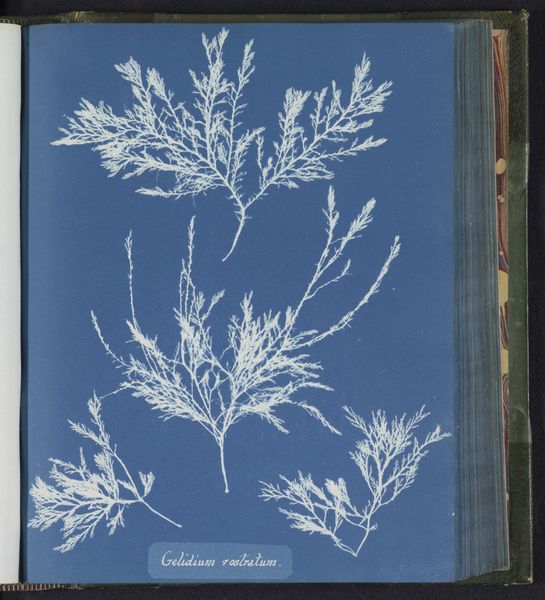

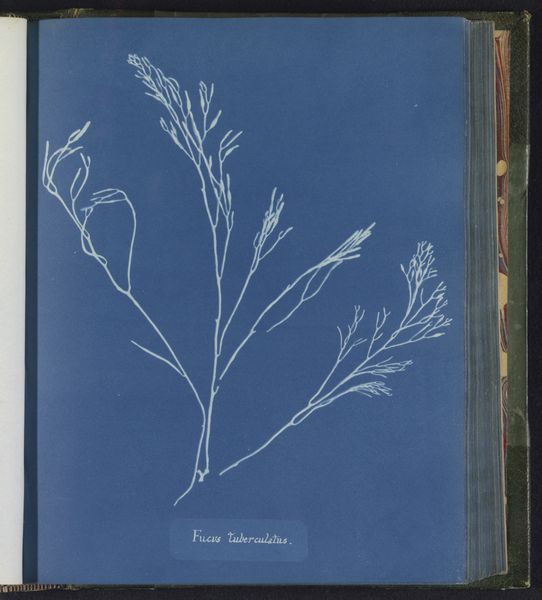

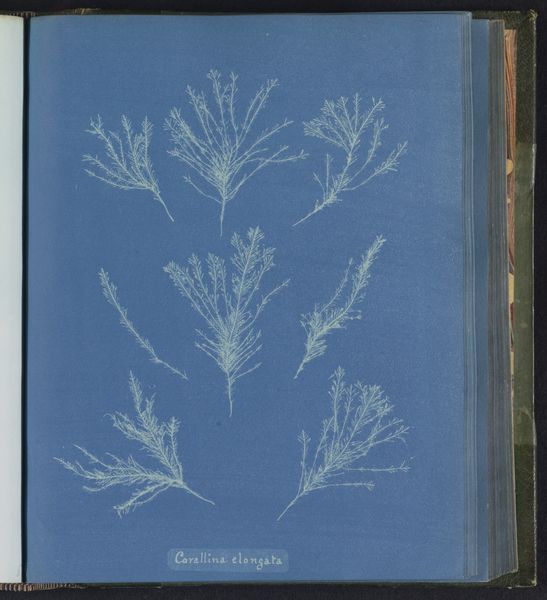

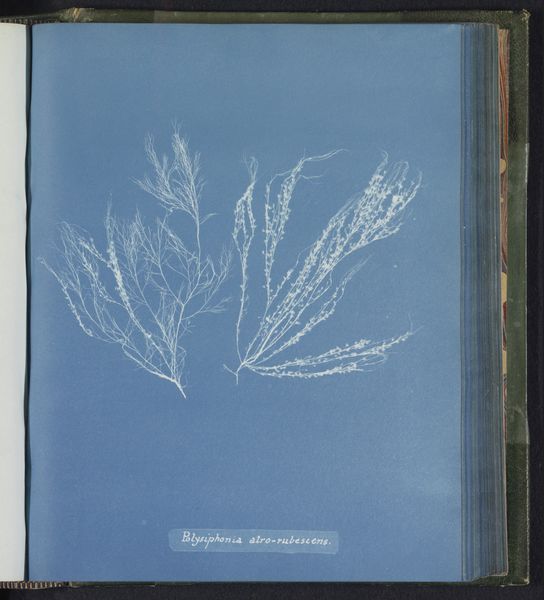

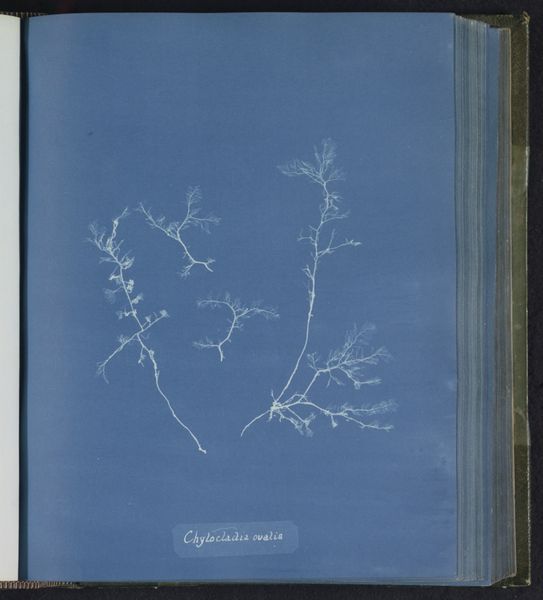

print, cyanotype, photography

# print

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Right now we're looking at Anna Atkin's "Fucus vesiculosus. var. linearis," a cyanotype from around 1843 to 1853. It depicts seaweed as a delicate white silhouette against a vibrant blue backdrop. It’s so simple, almost ghostly. What makes this work significant to you? Curator: For me, its significance resides in its place at the intersection of science, art, and the evolving role of women in 19th-century Britain. Photography was brand new. Atkins, a botanist, ingeniously used this novel technology, cyanotype, to document botanical specimens. How does this strike you? Editor: So, it’s not just a pretty picture, it's scientific documentation? Curator: Exactly! And consider the cultural context. Scientific illustration had always been meticulous hand-rendering, painstakingly copied by skilled draughtsmen. Atkins sidesteps all of that. She's democratizing the image, if you will, while also quietly subverting expectations for women in science at that time. Did Atkin's gender play a role, in your opinion, in her choices? Editor: I imagine so! Women weren't always encouraged or given access in the science realm like they are today. But if scientific illustrations already existed, then how did her artwork pave a way for future art movements? Curator: Great question. Her work foreshadows a move toward a more objective mode of representing reality, seen later in movements like Realism, though Atkins wasn't setting out to make 'art' per se. It shows that context often matters more than intent. Editor: It's fascinating how this image blurs the lines between art and science, reflecting the changing social landscape of the time. Curator: Indeed, and it reminds us how art is intertwined with social and technological advancements. There's more to this seemingly straightforward image than initially meets the eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.