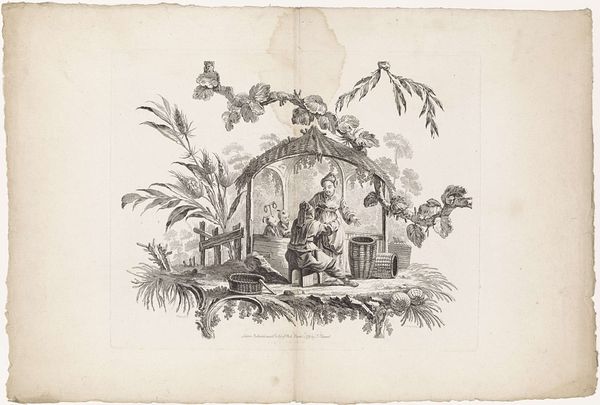

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 440 mm, width 550 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print called "Chinees gezin bij een prieel met begroeiing", depicting a Chinese family in a landscape, made in 1759 by François Antoine Aveline. Editor: It strikes me as a very constructed scene, almost theatrical, with that proscenium arch of vegetation framing the figures. You can almost hear the rustle of silk. Curator: Precisely. This type of imagery reveals a European fascination with the ‘Orient’ and a demand for chinoiserie during the mid-18th century. It speaks to larger systems of trade and collecting. Notice the carefully rendered details; each object and gesture contributes to a staged sense of authenticity. Editor: But staged is the operative word, right? The execution feels distinctly European—the linear perspective, the precision of the engraving... How might the actual crafting of this work inform our reading? The labor itself feels like part of the statement. Curator: Absolutely. While purporting to depict an "authentic" Chinese scene, it's entirely filtered through a Western lens. The engraver never knew this landscape first-hand. It perpetuates and normalizes this "idea" through its very production and circulation. The print medium allowed it to reach a broad audience. Editor: And think about the materials involved: the paper, the ink, the metal plate used for engraving. These would have been sourced and circulated through a complex economic system, literally embedding the print within networks of European commerce and consumption. The object becomes a commodity in its own right, irrespective of its claim to represent something “other”. Curator: Exactly. The art market created a desire, even an illusion of access, through visual reproductions. It allowed patrons who had neither the means nor perhaps the inclination to visit these faraway lands to consume and display images from them. The image functions as a tool of cultural and class aspirations. Editor: It's all about power dynamics, really. The ability to possess and reproduce this image, and circulate that perspective of another culture, is inherently rooted in material access. Food for thought. Curator: Indeed. Reflecting on this print really underscores how visual imagery becomes deeply intertwined with socio-economic forces, often with complicated and skewed representations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.