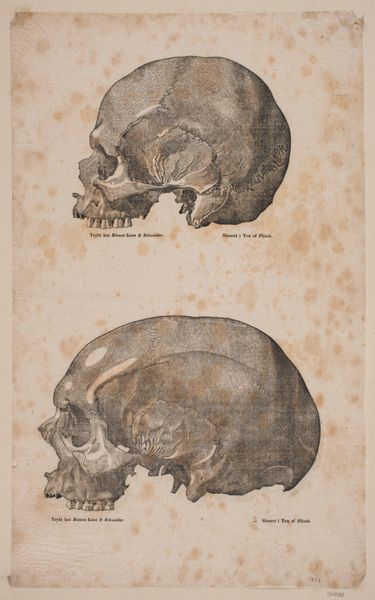

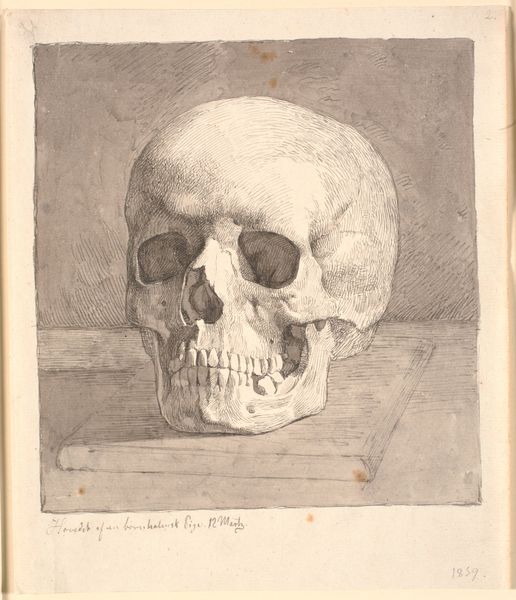

drawing, print, paper, woodcut

#

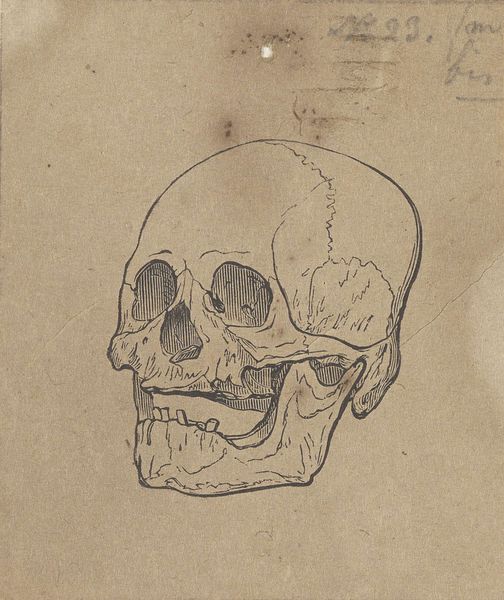

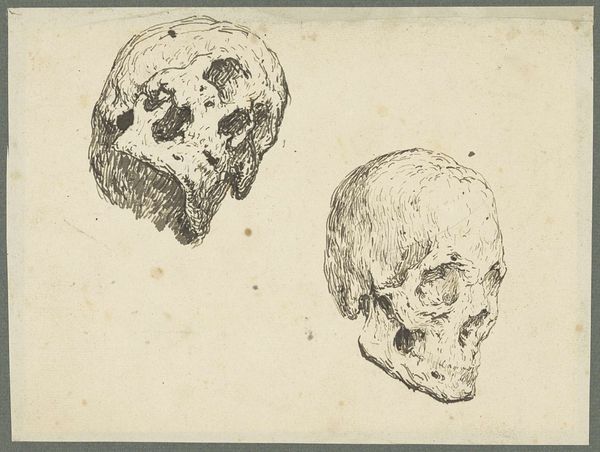

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

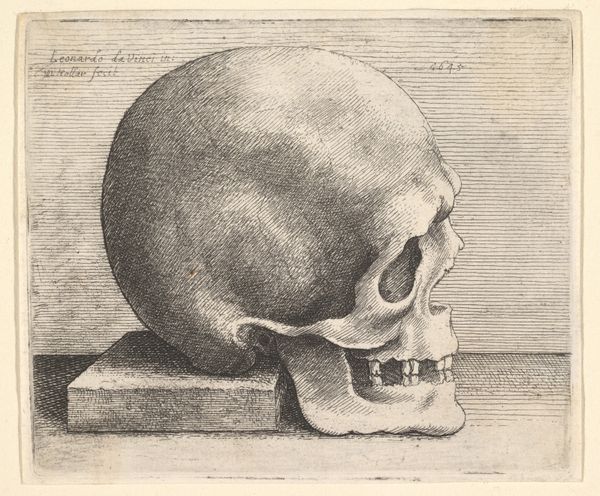

Dimensions: 137 mm (height) x 169 mm (width) (bladmaal)

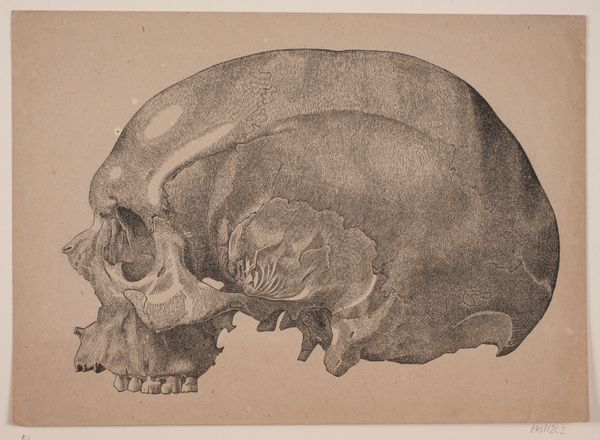

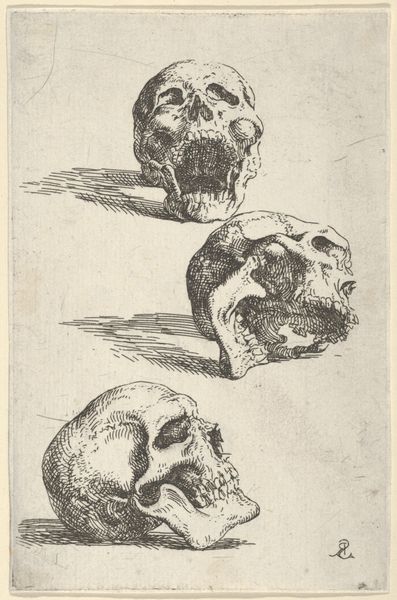

Curator: Here we have "Kranium," a woodcut print on paper, crafted in 1838 by Andreas Flinch. Editor: Immediately striking, isn't it? The weight of the skull seems to press against the page, almost breathing, and this close hatching... like a relentless sculptor revealing hidden truth! Morbid but elegant. Curator: Let's delve into the making. Flinch's choice of woodcut speaks volumes. The process, laborious and demanding, involved meticulous carving to create this singular print. The materiality of the wood itself lent a certain texture and a physicality that contrasts the ephemeral nature of life symbolized by the skull. Consider too, this wasn't simply an artistic rendering; anatomical studies like this were crucial for scientific and academic pursuits at the time. Editor: Absolutely. The density of line, carved bit by agonizing bit into wood feels so unlike the subject. It asks: Is this science, art, or, a kind of meditation on our fleeting time here. Wood, death and time all in one glance. Curator: Its accessibility also matters. Prints, unlike unique paintings or sculptures, allowed for wider distribution of knowledge. Anatomical prints like "Kranium" reached a broad audience from medical students to amateur artists eager to understand human form. It's also a very physical object: the specific qualities of the paper used, the wear and tear, or lack thereof – all contributes to the history of its production, circulation and even consumption. Editor: Right, consumption… it makes me think about how our perception of death has changed. Seeing such images was perhaps more common in a pre-photographic era. Now we are visually so protected that confrontation with this skull's honest stare is surprisingly moving. Curator: Indeed, the cultural context deeply informs our response. The Romanticism influence of the time played a part, too, often fixated on mortality and the sublime—think sublime terror, yes, but also the sublime in contemplating life’s fleeting moments, our shared vulnerability in this mortal coil. Editor: Well, staring back at it, it reminds me to treasure my fleeting moments and marvel at how someone could patiently create an object designed to trigger such thoughts. The human mind really is endlessly strange. Curator: So we find this object not only revealing insight into anatomical study of the era, but demonstrating human processes, materiality and techniques. Editor: And I find myself lost in thought…about the mystery inside and the fleeting time we get. All encapsulated in the dark and light lines of this captivating skull.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.