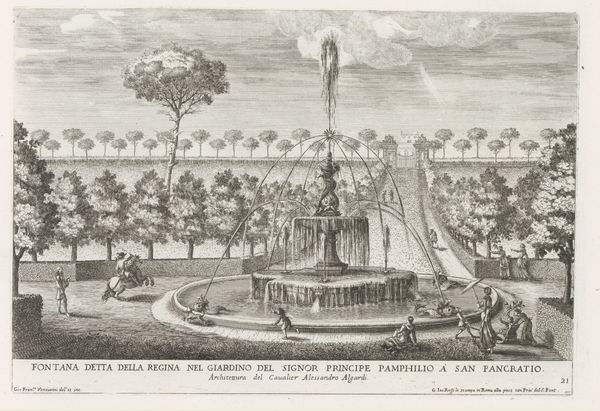

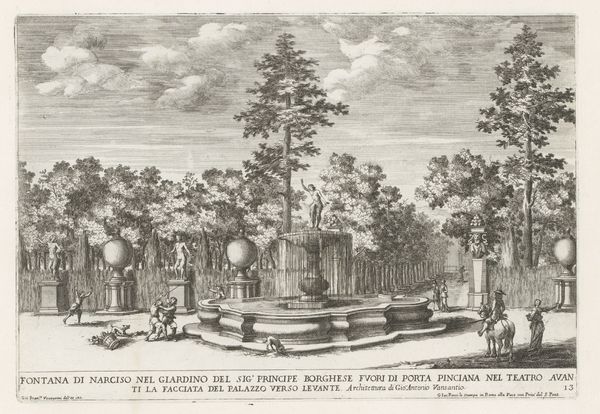

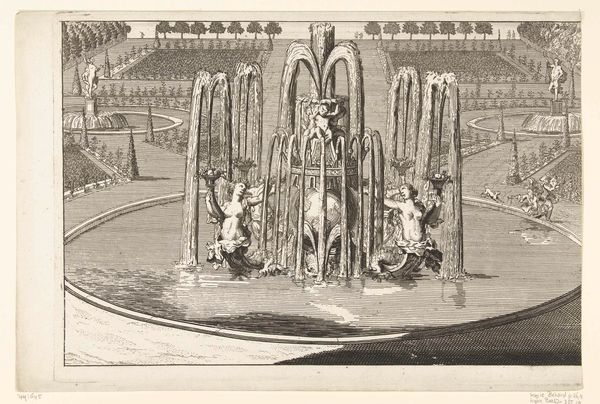

Fontana del Bicchierone in de tuinen van de Villa d'Este te Tivoli 1653 - 1691

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 242 mm, width 338 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

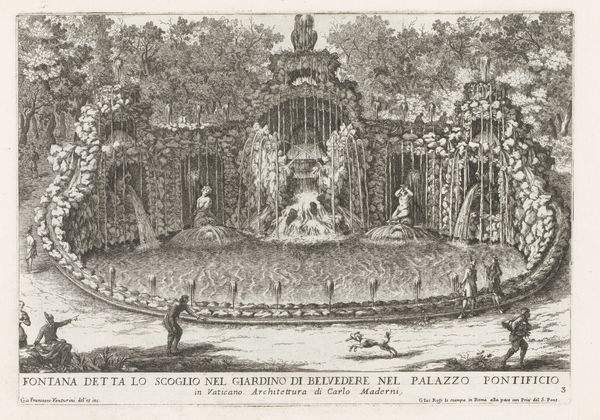

Curator: I’m immediately drawn to the almost dreamlike quality of this engraving. There's a formal geometry clashing gently with organic, chaotic nature. Editor: This is “Fontana del Bicchierone in de tuinen van de Villa d'Este te Tivoli,” a print made sometime between 1653 and 1691 by Giovanni Francesco Venturini. It captures the famous fountain and gardens. Look at the way Venturini represents the stonework, and also, those lovely trees. Curator: Yes! That seashell is striking, almost like a primordial form. It's a classical reference but the scale feels deliberately off, maybe suggesting the ephemerality of human achievements against the backdrop of timeless natural forces. Editor: Venturini was quite skilled with engraving; notice how he renders water in this print. The texture and line work really shows off his technical skill with the copper plate and the tools he used. I wonder about the social context. Was this intended for wealthy patrons visiting the gardens, as a souvenir of sorts, or to popularize Italian garden design amongst a wider audience via print culture? Curator: It could be both. Gardens like these were powerful statements – about control, wealth, and taste. The water, always manipulated, symbolizes a mastery over nature. And shells themselves carry so much symbolic weight. The suggestion of birth, femininity, and even pilgrimage – after all, the shell is Saint James' emblem. These gardens spoke a language, coded to those who understood. Editor: Definitely. Engravings like this circulated ideas and styles, impacting gardens and tastes across Europe. The printmaking process itself involved collaboration too – from the artist's design to the engraver's skill to the printing and distribution networks. It wasn’t a solo affair, and these practical aspects of art production interests me immensely. Curator: Absolutely. The beauty here lies in the illusion of control over wild nature—a central tension throughout the Baroque period. Editor: Examining the social lives of materials like paper and ink broadens our understanding of art, not just as aesthetic objects, but as part of wider societal networks. Curator: Thank you; this print is a reminder that even landscapes can be rich with symbol. Editor: Yes, considering material production also makes you appreciate these wonderful fountains in a very real and immediate way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.