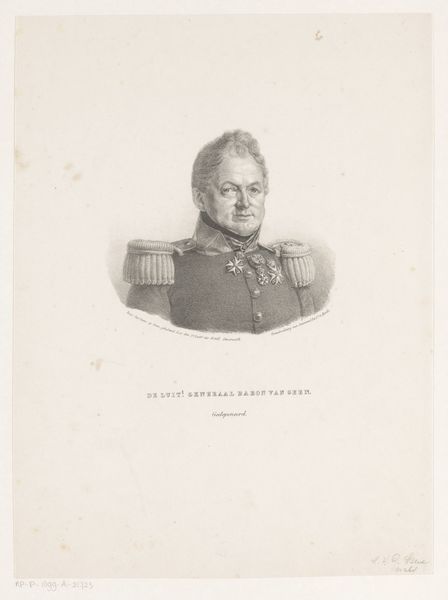

Z.E. den Luit Generaal J. van Geen, opper Bevelhebber van het mobile Leger c. 1830 - 1845

0:00

0:00

wjvanoosterzee

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 326 mm, width 250 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

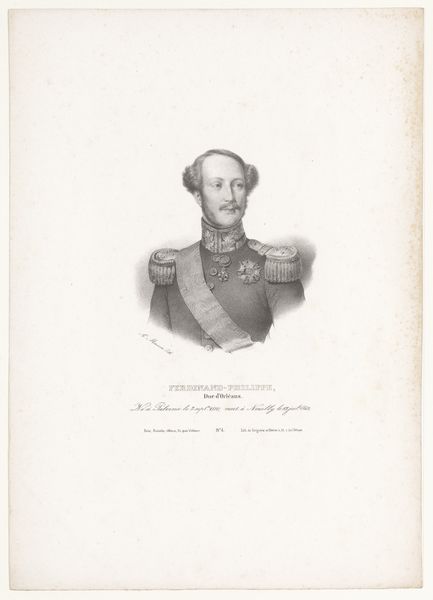

Curator: Looking at this, what immediately strikes me is the rigid formality, that carefully etched severity of expression. Editor: Well, let’s delve into it. This is "Z.E. den Luit Generaal J. van Geen, opper Bevelhebber van het mobile Leger", dating roughly from 1830 to 1845. It's currently housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Created using ink on paper, the artist was W.J. van Oosterzee. Knowing that title situates the work quite clearly in a historical and political framework. It isn't simply a portrait; it is a statement of power, deeply embedded in 19th-century societal structures. Curator: Absolutely. It feels almost…imposing, doesn’t it? The high collar, the decorations… it’s a declaration of authority but, perhaps subconsciously, a vulnerable rendering of masculine power in that era. The gaze, while firm, is almost melancholic. What were the visual cues available at this moment to project one's own agenda in post-Napoleonic Europe? Editor: Precisely. The choice of ink on paper lends itself to that stark contrast, heightening the formality but it simultaneously speaks to accessibility. This image would likely have served a public role, reproducing and disseminating the general's image for the purposes of creating a certain sense of national unity. These images acted almost like today's propaganda campaigns. Curator: That’s an interesting intersection of the personal and the political. Could this level of access also offer us a glimpse into questions of identity, like the relationship between masculinity and militarism in the context of early 19th-century Dutch society? This connects to larger socio-political questions about war, governance, and identity creation. The clean, sparse composition allows the face to become this symbolic battleground of projected intentions and lived experience. Editor: And we need to consider the influence of Romanticism during this period. Although clearly aligned with classical-realism, there’s an element of idealization at play here – perhaps in how the lighting flatters, in the very deliberate positioning and confident facial expression. It would be an era in which those who have the power in society want to demonstrate it via commissioned images that have both artistic talent and practical utility in governance. Curator: Definitely. Understanding the work through these historical lenses provides access to broader societal conversations. The very specific aesthetics become these access points. Editor: Examining this piece, especially in terms of its artistic origins and sociopolitical impacts, offers insights into that very turbulent and formative time period. It serves as a fascinating look into power, representation and that post-Napoleonic quest for meaning and stability.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.