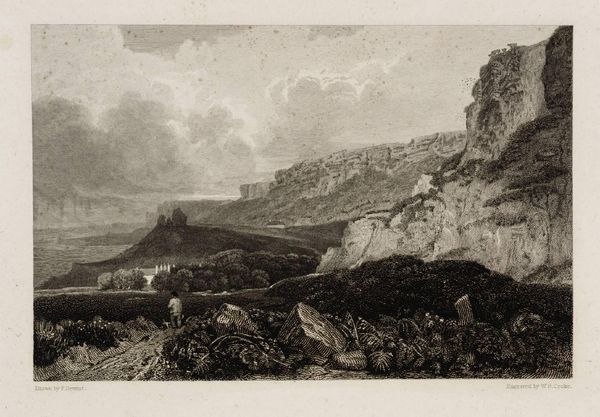

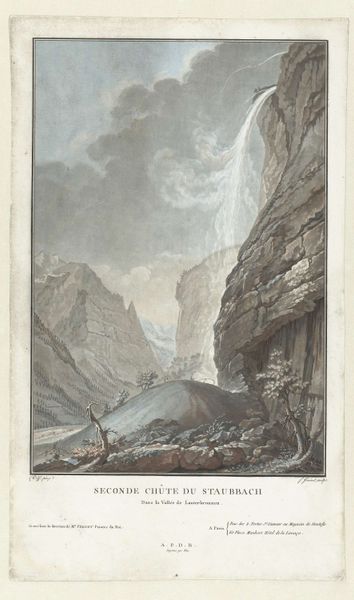

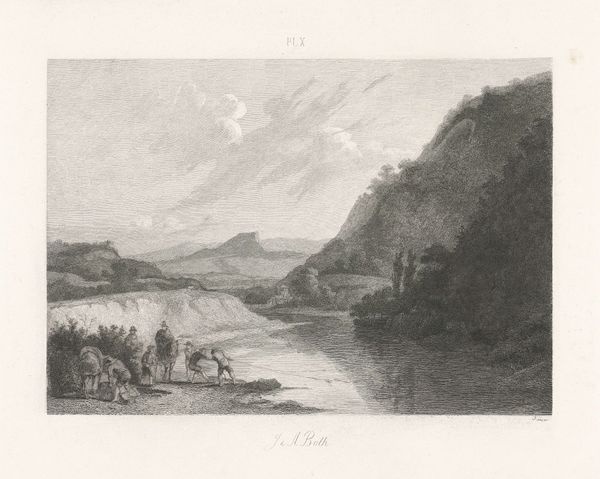

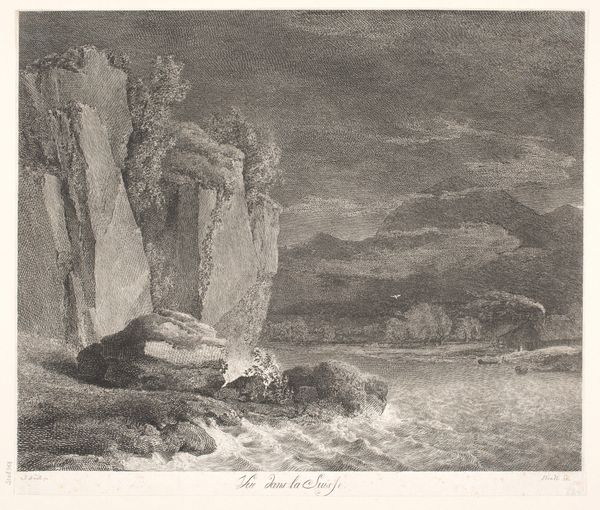

print, photography, engraving

# print

#

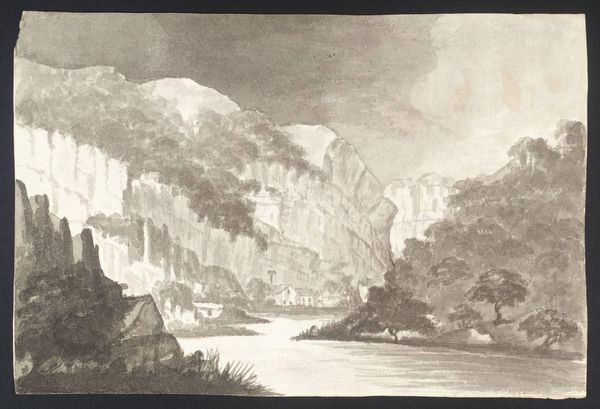

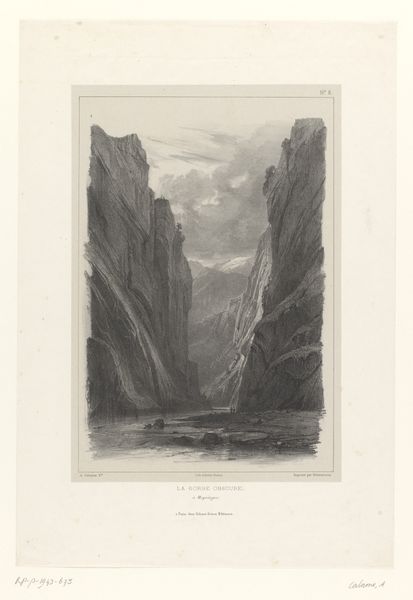

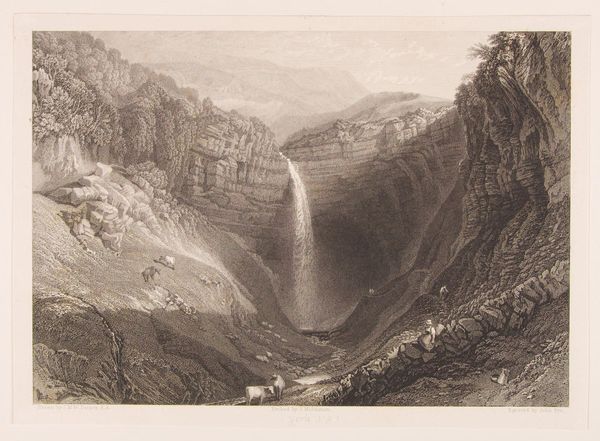

landscape

#

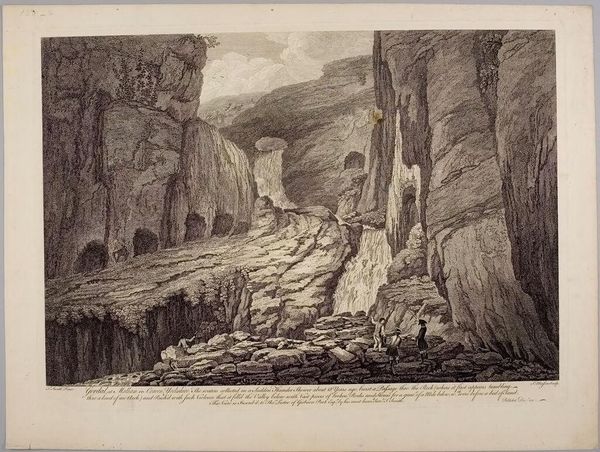

figuration

#

photography

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: Public domain

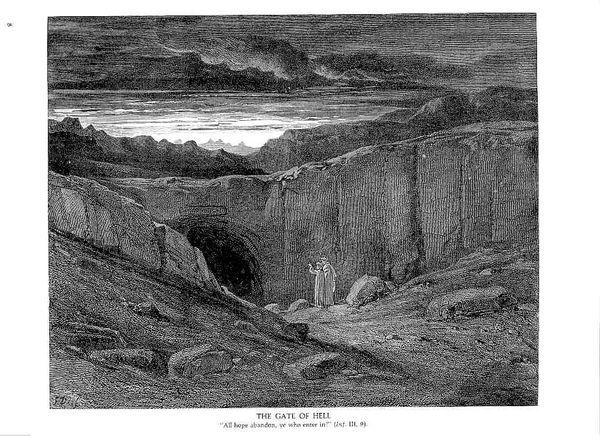

Editor: So, this is Gustave Dore’s "Inferno Canto 3." It looks like an engraving, probably done sometime in the 19th century. It’s a really dramatic landscape – stark, dark, and honestly, pretty terrifying. What strikes you most when you look at this piece? Art Historian: Thanks for setting the stage. Immediately, I’m drawn to how this image operates as a cultural reflection. Dore, illustrating Dante’s Inferno, taps into deeply ingrained anxieties about morality, punishment, and the social order. The visual language—the dramatic lighting, the sheer scale of the chasm—isn’t just about illustrating hell; it's about reinforcing a specific power dynamic and cultural expectation, right? How does the landscape itself contribute to that feeling of terror you mentioned? Editor: Well, the depth of the pit is immense, and the figures are so small in comparison. It emphasizes their helplessness, and, by extension, our own. The inscription below says “All hope abandon, ye who enter here,” confirming this feeling! But wasn’t Romanticism supposed to be about the sublime and awe-inspiring nature, not necessarily fear? Art Historian: Exactly! You’ve hit on a crucial point. Dore's work isn't a straightforward celebration of nature. The sublime here is twisted, weaponized even. Think about the social context of 19th-century Europe: rapid industrialization, growing social inequalities, strict class structures. Could this “hellscape” also be a commentary on the societal injustices of his time? The figures almost appear trapped by their surroundings and power structures that determine their existence. Editor: So, it’s less about a literal depiction of hell, and more about…a visual representation of societal anxieties? Art Historian: Precisely! Dore uses the familiar imagery of hell to critique earthly power structures. And the gendered implications are worth considering, too. Who traditionally gets assigned blame and punished in these systems? Whose suffering is deemed justifiable? Editor: That’s…wow, I never thought about it that way. So, looking at this isn't just about seeing a scary picture. Art Historian: Not at all. It's about unpacking the visual and historical codes Dore employs to explore power, oppression, and who gets to define “good” and “evil." I might consider the relevance and universality of these concepts today, particularly with current geopolitical conflicts and the struggles many individuals experience against large organizational bodies. Editor: Thanks; this engraving now sparks curiosity more than fear; now I can explore Dore’s themes through new narratives!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.