#

quirky sketch

#

pen sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

#

fantasy sketch

#

initial sketch

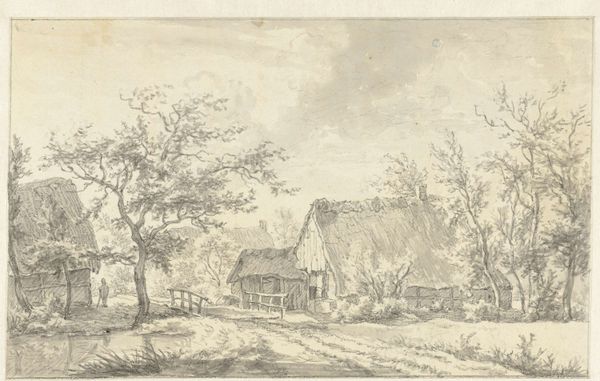

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 87 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Huis in Enkhuizen," a pen and ink sketch, potentially with watercolor, done sometime between 1650 and 1659 by Harmen ter Borch. It's quite minimal, almost like a quick notation. What's your take on a sketch like this from a historical perspective? Curator: It's tempting to dismiss these personal works as less important, but these "quick notations," as you put it, offer invaluable insight into the artist’s world and, crucially, their process. This isn't a finished commission piece, but a direct engagement with his environment. Think about Enkhuizen as a port city – what stories might this house hold about trade, travel, and the social fabric of the time? Editor: So you see its value not just in the artistic skill but in its connection to a specific time and place? Curator: Precisely! Consider the role of the sketchbook itself. In the 17th century, it was a relatively new phenomenon, tied to the rising status of the artist as an individual observer and interpreter of the world. It also marks the development of early tourism – the rising merchant class using these small drawings as keepsakes or even a form of social currency. What do you make of the somewhat imprecise, even 'unfinished' nature of the sketch? Editor: I see how the incompleteness makes it feel more immediate. It’s not trying to impress anyone, just a quick capture. Is there something inherently democratic about these types of sketches, bypassing the formal patronage system? Curator: Absolutely. It exists almost outside the formal structures of art production, offering us an unvarnished glimpse into ter Borch’s personal engagement with his surroundings. We see the everyday and thus also recognize ourselves, however indirectly, in it. This house becomes less a building and more a signifier of social, political and personal interaction with space and society. It shifts how we consider 17th-century artistic output, doesn't it? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way. It's less about high art and more about the democratization of seeing. Thanks for the fresh perspective!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.