engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

landscape

#

15_18th-century

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 503 mm, width 352 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

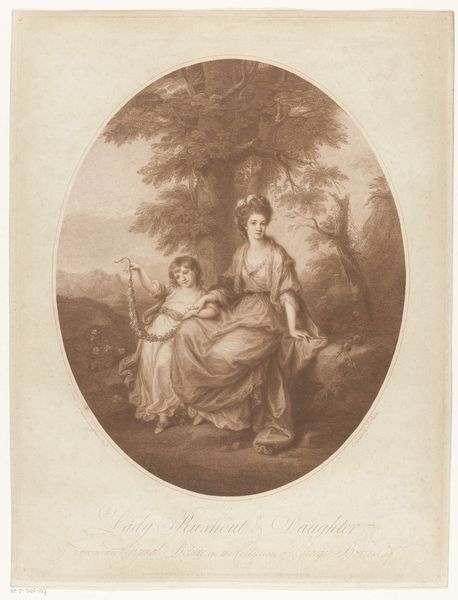

Curator: Looking at this 1766 engraving, “Portrait of Mary Leslie” by Jonathan Spilsbury, I’m struck by the serene, almost ethereal quality of it. It's a really peaceful composition, isn't it? Editor: It is… overwhelmingly *soft*. Everything is rounded, blurs. What jumps out is the sheep: foreground, background, nuzzling… The animal almost becomes a fabric in the visual tapestry. An engraving must have been chosen very carefully; the artist had to believe that the materiality of that mark making served his subject. Curator: Exactly! And this wasn't just any sheep. During the Neoclassical movement, imagery from idealized pastoral scenes offered the nobility a harmless vehicle for the values of hard work, innocence, and simple beauty. What's also interesting, from a purely material perspective, is the scale in which the portrait flattens Mary’s expression as well as the flock of sheep. Her gaze meets the viewer, unsmiling. She’s contained by that lack of nuance, don’t you think? Editor: Contained by and elevated by. The material processes here also flatten social ones. See the amount of craft involved in making something easily reproduced. This engraving—its labour—is circulated to ennoble the family as "worthy" of this vision. So who were the consumers of the artist's production, I wonder? And the many workers needed to support Spilsbury’s practice? Curator: It definitely prompts one to think about status and representation at the time. It makes one question the sitter: did Mary embrace or merely embody the romantic vision of virtuous simplicity being projected? How often did these affluent sitters control their image as a means of self promotion and control in high society? Editor: Right—think of all the resources and collaborative labour that enabled this portrait! Paper and ink production, skilled craftsmanship… these things give access. It speaks to a system that allows these images and status to be so widely consumed. In fact, I read once that this artist worked in mezzotint - an intaglio printmaking process--and it produces those wonderfully rich tones we are speaking of--allowing the artist to capture depth in a single color, further manipulating material and class constraints. Curator: It certainly brings new depth to viewing the work. Next time I look at this piece, I’ll reflect a little longer on the nuances within this single-colour medium. Editor: Precisely—every element carries a quiet weight of expectation and access.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.