Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 152 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

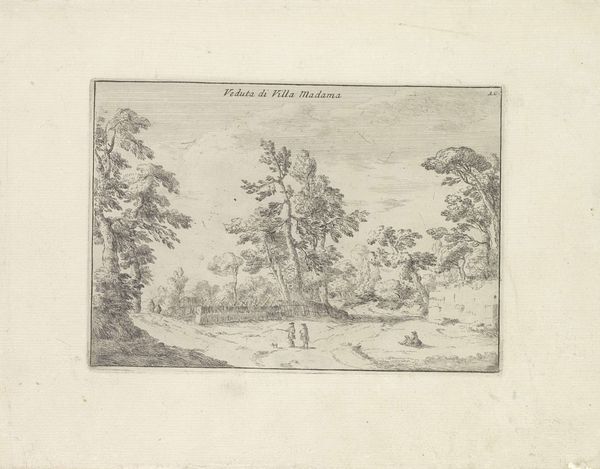

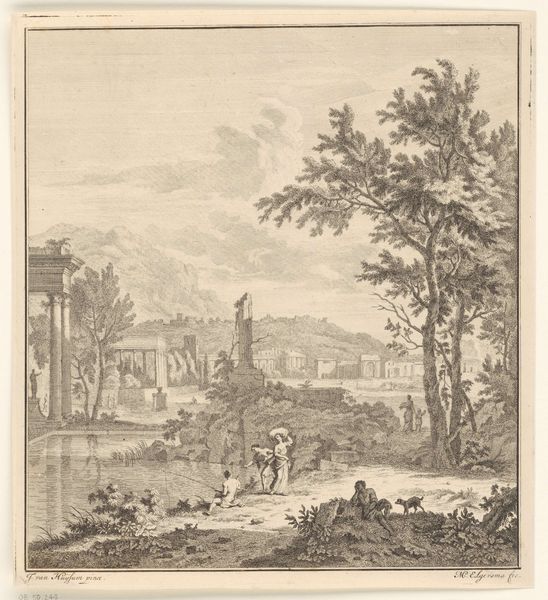

Curator: This is a delightful engraving by Leendert Brasser, made sometime between 1727 and 1793. It's titled "Vignet met rivierlandschap en regenboog in wolken," which translates to "Vignette with River Landscape and Rainbow in Clouds." It’s currently part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My immediate impression is a kind of idyllic melancholy. The delicate lines, the muted tones, it all evokes a sense of longing. And those trees framing the scene—they almost feel like curtains on a stage. Curator: Exactly! It captures the emerging Romantic sensibility. The focus on nature, the almost theatrical framing, points to a growing interest in emotion and the sublime. Note the artist's choice of engraving which democratized images at this time and spread them widely to all classes of society. Editor: I’m drawn to the engraving technique itself. The fine, precise lines speak to a highly skilled craft, laboriously produced with careful intention. It reminds me of the intense material processes behind image-making. We have this idyllic fantasy but we should take account of its construction too. Curator: Certainly. And think about how this image circulates. It's not just art for art's sake. It becomes part of a visual culture, shaping ideas about nature and perhaps even national identity. Were images like these being distributed primarily amongst wealthy collectors or disseminated more broadly, affecting popular understanding? Editor: That's a critical question. And it makes me consider the role of the artisan versus the artist. Was Brasser considered a craftsperson, a maker of multiples, or an artist expressing unique vision? These categories matter as much now as they did back then in establishing image economies. Curator: They do indeed. This print is also a fascinating reflection of 18th-century aesthetics, and this is revealed in what’s included—the picturesque landscape, the shepherds with their flock, the symbolic rainbow representing promise and divine blessing. It really reinforces certain idealized ideas about the world, but who got to hold them, I ask. Editor: And maybe those idealized images conceal a more complex social reality. This work opens up questions about art, production, labor, and consumption practices—the very conditions that made this idyllic image possible in the first place. It is very picturesque in a carefully orchestrated kind of way! Curator: True. Reflecting on this print underscores art's place within a network of societal forces shaping aesthetic sensibilities of that period, with a specific look to who held influence. Editor: Absolutely. It urges us to appreciate the beautiful skill and labor involved, but also question the values and politics embedded within this manufactured vista.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.