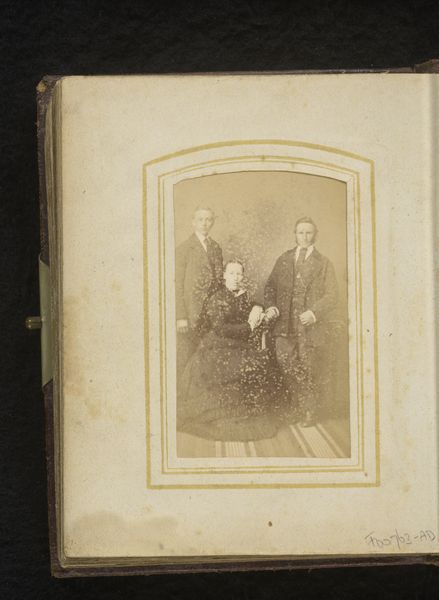

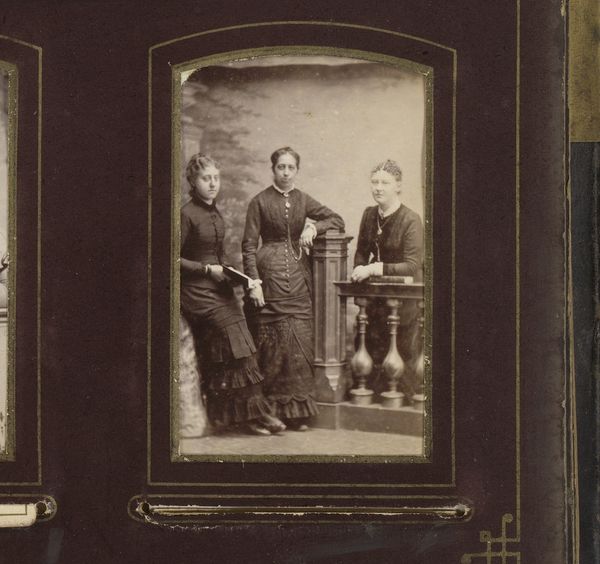

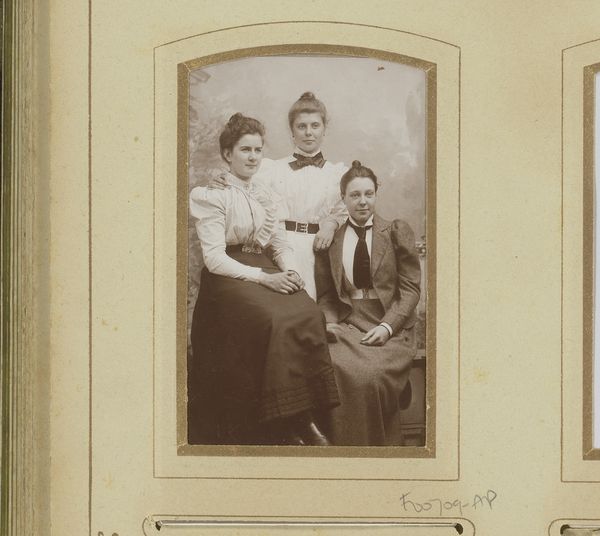

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister’s “Portret van drie meisjes,” or “Portrait of Three Girls,” a gelatin silver print likely made between 1877 and 1883. It’s immediately striking, don't you think? The composition has such stillness to it. Editor: Stillness, and an odd sort of labor showing itself! Look at the way those girls are dressed. It’s fascinating to me how much detail has gone into the ruffles and folds. What were their lives like? Who made the dresses? All that intense detail sewn into heavy dark wool, likely by someone who saw none of the status afforded the wearers... Curator: Yes! It does invite questions. The materiality here feels particularly poignant. It speaks to an almost tangible weight of expectation, perhaps? The photo feels laden with unspoken stories. Their gazes hold so much… solemnity? Maybe that's the wrong word. It is an artfully staged scene, though—a studio photograph, designed to convey respectability. Editor: Designed to look respectable, absolutely! But respectability is *work*. Making and maintaining appearances. Those complicated dresses needed to be constantly repaired and cleaned by someone, and I bet it wasn't those children. It reminds us that images always have hidden labor costs. Also the gelatine, it was extracted through the work and violence enacted on animal bodies... Curator: The violence is always part of the picture, isn't it? Even in portraiture. Yet beyond the undercurrents of class and industry, the image also breathes a delicate innocence. You can feel it in the awkward postures of the girls, how they haven’t quite learned to pose. They seem like they are holding back laughter or conversation, so it makes you wonder who they really were behind the trappings. Editor: Behind those painful, itchy frills and buttoned-up sleeves! Thinking about those garments – the physical demands of creating something so elaborate… it is a testament to hidden histories, of exploited labor as well as the beginnings of accessible photographic methods. These gelatin-silver prints democratized image-making, sort of. Curator: Leaving an imprint nonetheless, across lives and history itself. That’s why even with the studio constraints, even with my initial thoughts of staged performance, there’s something genuine still. And the interplay—between representation, aspiration, and social force, so to speak—lingers long after viewing it. Editor: I agree. These quiet images are worth spending time with; a good antidote to the flood of instantly consumed images of today. There's a power in slowing down, contemplating the sheer effort, visible and invisible, that shaped them and which they continue to show us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.