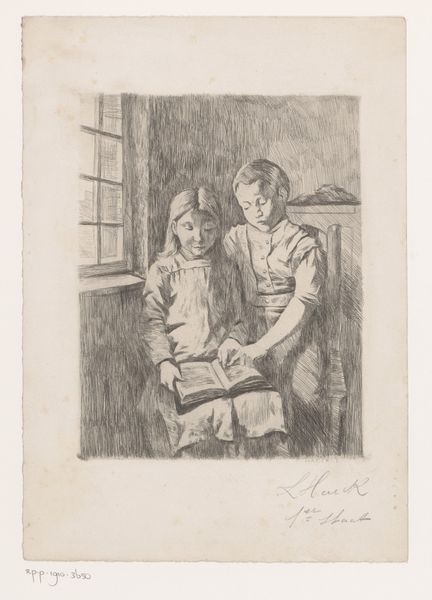

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

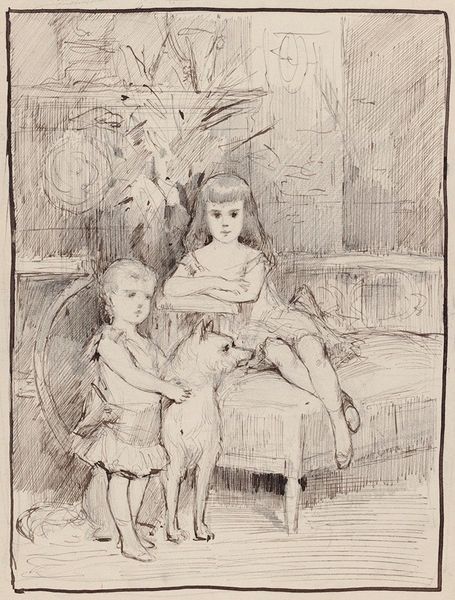

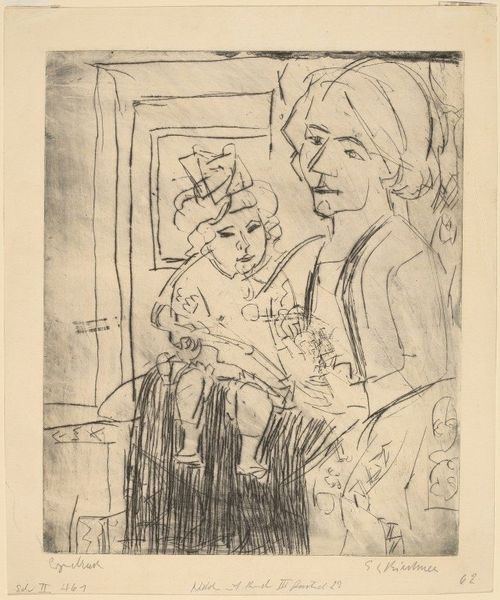

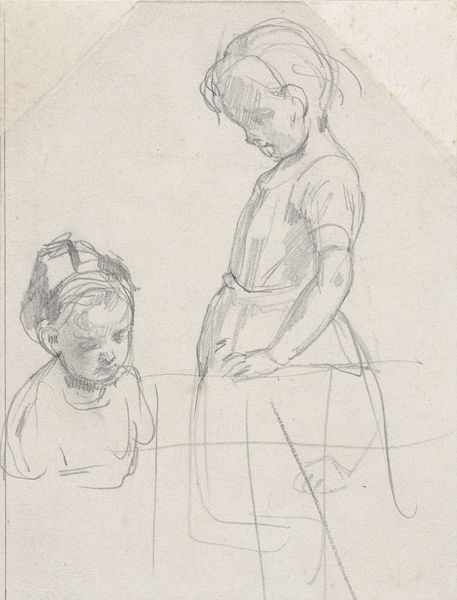

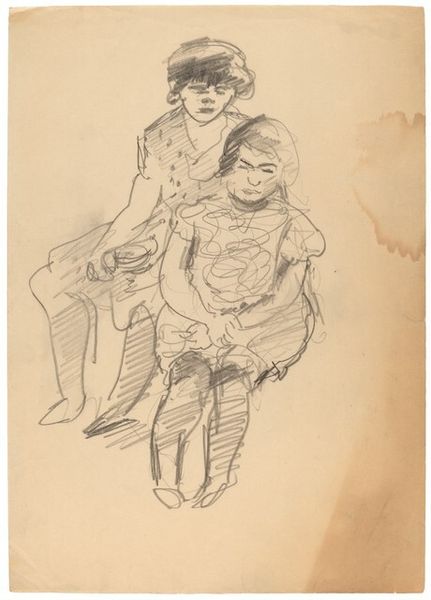

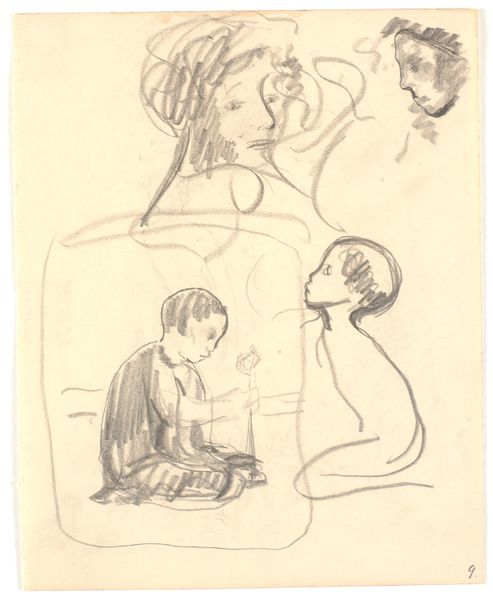

Curator: Ah, this sketch feels incredibly intimate. Look at how softly the light seems to fall. Editor: Yes! It's like catching a glimpse into a private world, a memory half-formed. There's a dreaminess to it, even a touch of melancholy. Curator: We're observing "Study, Kirill and Boris Vladimirovich" by Albert Edelfelt, a piece completed around 1881. The work is largely rendered in pencil. Edelfelt was known for his portraits and genre scenes; you see influences from realism blended with emerging impressionistic techniques. Editor: It’s more than just a study, isn’t it? The kids seem so natural, absorbed. It's like we walked in mid-scene. Boris looks really into that book. And Kirill looks, well, resigned. I wonder about their story? Curator: Children in art often serve as symbolic carriers, emblems of innocence, vulnerability, or perhaps, continuity. In 19th-century Russia, children of aristocratic families occupied a very particular place – objects of affection and also symbols of dynastic hope. Does their posture give you a feeling about them? Editor: It does! Maybe it's because of how Kirill looks straight out. His dark eyes do pull me in. But together they signal this passing of time, maybe this heavy dynastic history as you say. He is also wearing white that looks pure or royal, like ceremonial clothes for some function. Curator: You sense the tension perfectly. The white clothing contrasts well to a more serious dark background. They’re on the cusp. They are individuals, captured in a fleeting moment of childhood but already bearing the weight of expectation, caught between those things. Editor: Looking at Boris fully engaged with that book brings something nice to this somberness, though. Books are escape, a sort of counter weight. So here is Kirill directly engaging with dynastic burden while Boris can imagine alternatives by reading. Maybe! Curator: Beautifully put. What’s fascinating is that Edelfelt doesn't tell us outright; he invites us to interpret. Editor: It is the heart of what makes art so good, isn't it? We put a piece of ourselves, and of our time into seeing. I have no way to tell those things, but they are in there somehow and came here together when I saw it. Thank you. Curator: Exactly. It's about recognizing that our own perceptions contribute to its significance. Thank you for joining me!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.