Copyright: Public domain US

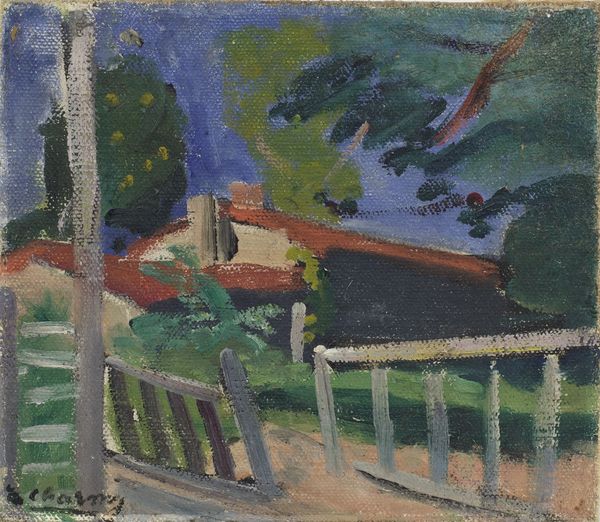

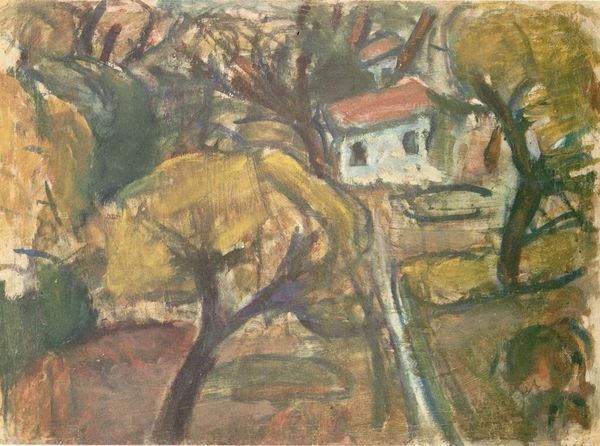

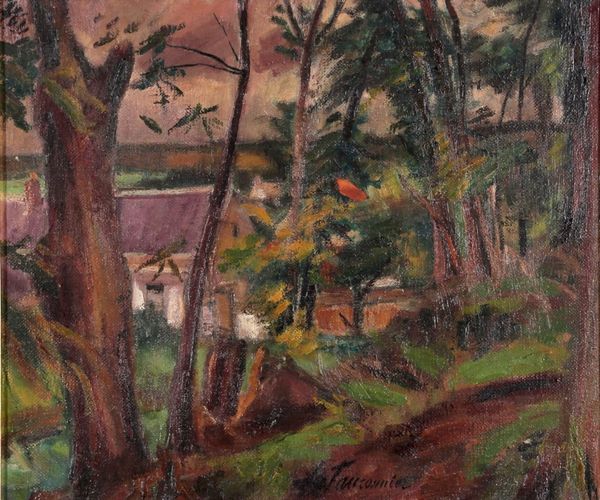

Editor: We’re looking at “Marnat,” a 1914 oil painting by Émilie Charmy. It feels so immediate, like a quickly captured impression of a garden. There’s a raw energy in the brushstrokes. What stands out to you? Curator: It’s precisely this raw energy that captivates me. Look closely at how Charmy handles the oil paint, those visible, unblended strokes. What does that choice of material application communicate to you? Editor: It feels almost unfinished, breaking down the illusion of reality. Was she challenging traditional painting techniques? Curator: Absolutely. Charmy’s rejection of polished surfaces speaks volumes about her social context. Consider the rise of industrialization and mass production at this time. By emphasizing the *act* of painting – the physical labor, the materiality of the oil itself – she subverts the idealized notion of art as a purely intellectual pursuit. How does the seemingly casual plein-air style then relate to this critique, in your opinion? Editor: I guess it’s making the means of production visible. It feels more about the artist's *work* than trying to imitate nature perfectly. It brings painting closer to the realm of manual labor. Curator: Exactly! She highlights the work that goes into constructing the image. It begs us to question not only what is represented, but also how it is made, and the societal implications of artistic production. Editor: That really shifts my understanding. I initially saw it as just a pretty landscape. Curator: And that’s the power of a materialist approach! It's a reminder that art is not created in a vacuum, but rather it is a product of social and material conditions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.