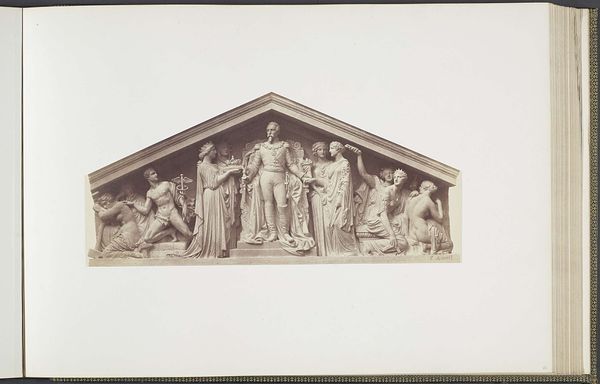

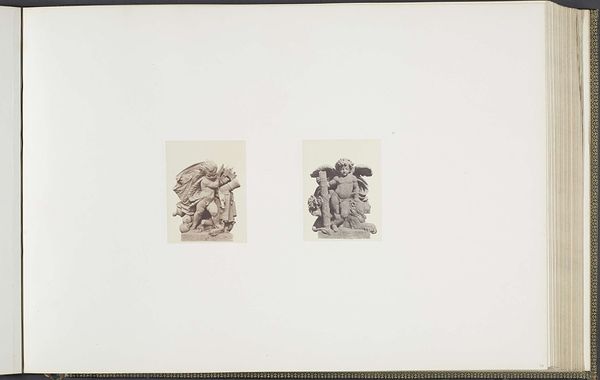

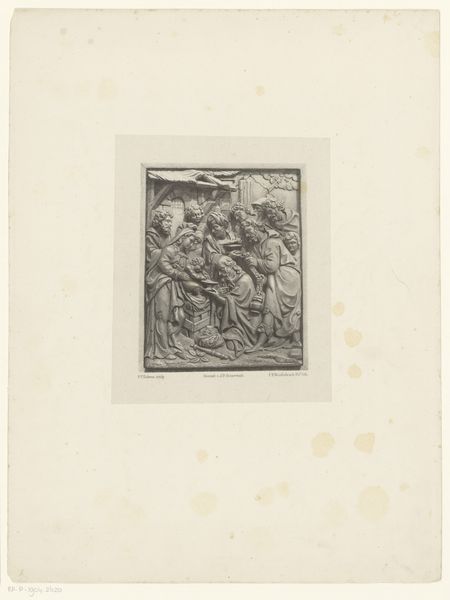

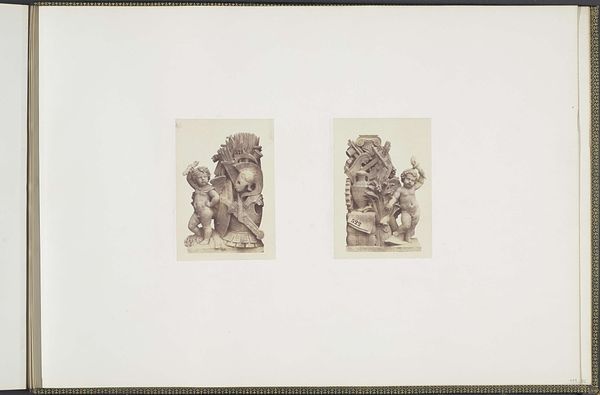

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 556 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

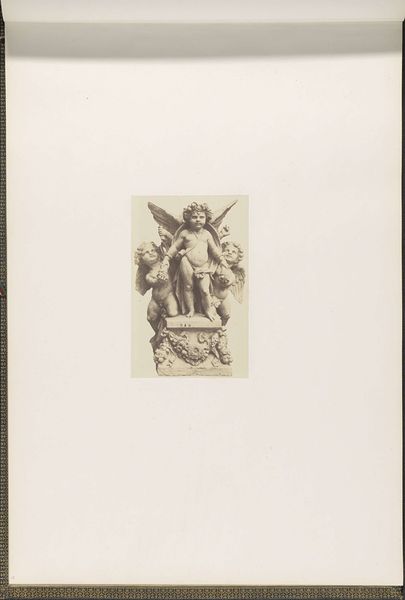

Curator: What a fascinating image. This gelatin-silver print by Edouard Baldus, taken between 1855 and 1857, presents a plaster model intended for a sculpture at the Palais du Louvre. Editor: My first thought is "monumental"—even in this photographic representation. The allegorical figures, the putti, that central shield... they convey an undeniable sense of power and permanence, although the tonal range seems so constrained. It appears chaste. Curator: Absolutely, the restrained tones contribute to its imposing character. It speaks to the rise of national identity, of imperial ambitions legitimized through the careful articulation of iconography that borrows heavily from Greco-Roman ideals. Those idealized forms naturalize the authority of empire, obscuring the violence inherent within those structures. Editor: Those angelic figures definitely resonate with earlier imagery, suggesting ideas around both triumph and the divine right to rule, notions very carefully cultivated within the iconography surrounding the monarchy and then adapted during the age of empires. And the babies add to the sense of establishing something enduring for the future, perhaps a dynasty or nation. I wonder about the hidden language held within that coat of arms above. Curator: Precisely! The artistic language adopted at the time aimed to portray France as the legitimate inheritor of classical grandeur, an endeavor often rooted in the erasure and subjugation of other cultural narratives. This wasn’t simply about aesthetics. This was political work. It shaped public perception and legitimized specific power structures, something often overlooked when we view these historical works. How can we critically engage with this history when so much blood lies beneath the plaster and silver? Editor: Yes, art offers a looking glass back through the corridors of power, one often mirrored by state symbols and artistic trends of the era. The way it ties back to collective cultural memories... How certain forms come to represent larger cultural concepts such as nationhood or heroism. To study these symbols and understand their evolution—it's like unlocking hidden narratives. The picture evokes strength but it also shows us its fragility, being made of plaster. Curator: Agreed, it allows a more nuanced conversation about these historical projects, and maybe to reshape and reclaim the very ideas behind "nationhood" or "heroism," embedding ethics of equality in place of inherited dominion. Editor: So next time when someone states 'that is ancient history'... We'll know where to send them for lessons!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.