painting, print, paper, watercolor

#

medieval

#

water colours

#

narrative-art

#

painting

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

history-painting

#

international-gothic

#

watercolor

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

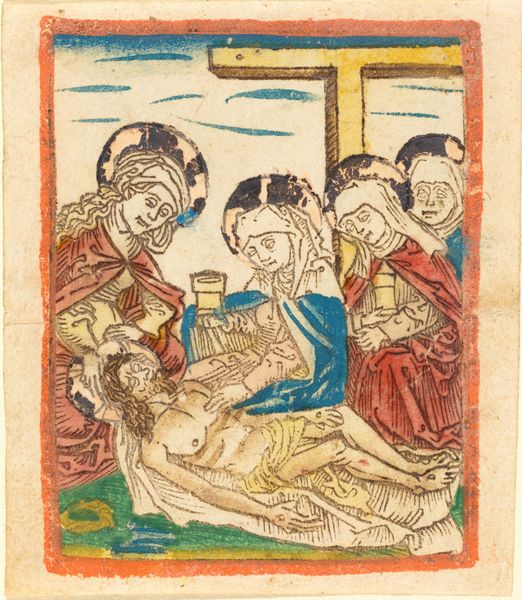

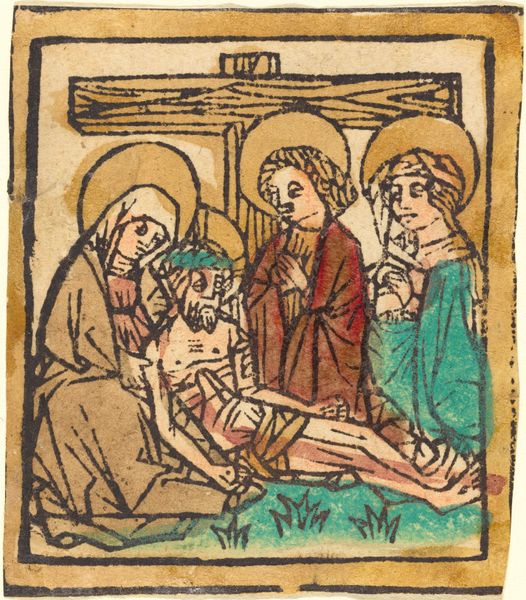

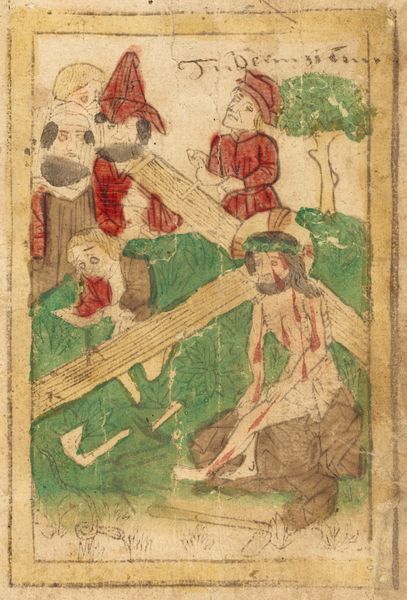

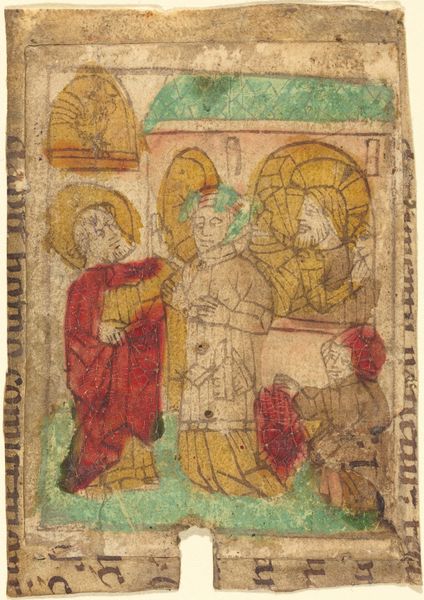

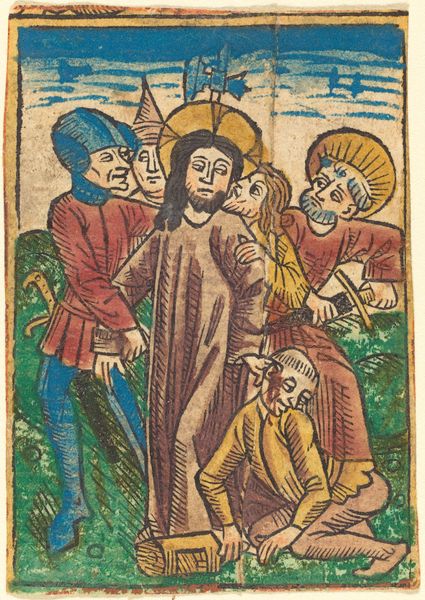

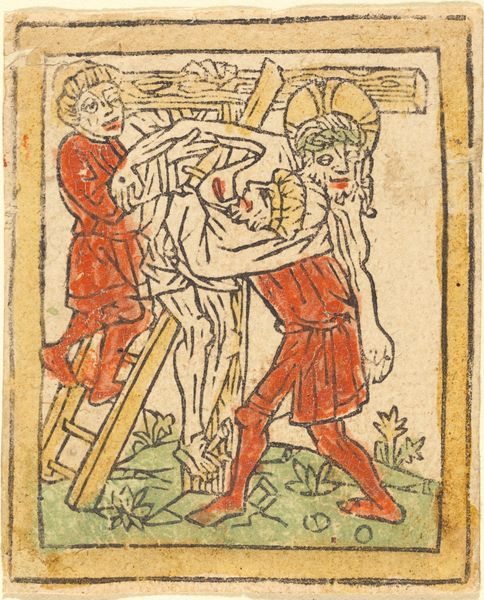

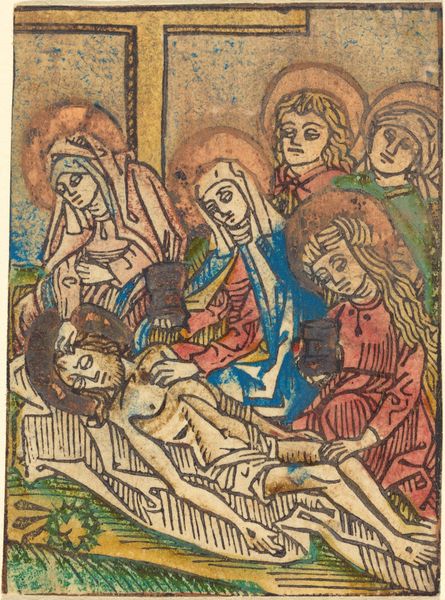

Curator: This poignant artwork is called "The Lamentation," dating back to between 1470 and 1480. It’s an anonymous piece, rendered in watercolor and possibly coloured pencil on paper. Editor: It immediately evokes a sense of stillness, doesn’t it? The colour palette is muted, lending a sombre mood. I’m struck by the raw emotion depicted, the way they huddle together almost as if trying to shelter one another. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the social and religious implications of the Lamentation scene. It speaks volumes about grief, particularly the depiction of maternal mourning, something historically excluded. To visually represent this opens doors for wider audiences, granting validity to suffering. The artist’s decision to portray this private moment publicises it for all, offering solace but more critically, challenging patriarchal structures. Editor: Yes, that maternal connection is central. The Virgin Mary holding her son becomes the ultimate icon of suffering and grief, repeated throughout centuries. Look at the visual weight placed on the supporting figures—their halos become almost looming discs, intensifying their presence but flattening as icons of their own grief too, an overwhelming circular symbol. They seem unable to support the immediate devastation yet the palette is deliberately childlike and limited, hinting perhaps, to innocence or an intended universality, which only adds to the work’s pathos. Curator: Precisely, by flattening depth the audience cannot avert from facing loss, made raw by the absence of classical technique. It disrupts conventional displays of mourning, aligning it more towards societal experiences that aren’t centered in traditional canons or art spaces, giving voice to unseen demographics, like the plight of lower-class mothers who’s narratives aren’t being historically preserved or even remembered. Editor: It's a stark, distilled representation of shared sorrow, which resonates regardless of religious belief. The figures have that strangely comforting detachment from the horrors and pains, focusing, really, on a deeper state of contemplation beyond tragedy. Curator: Examining this piece in a contemporary setting opens possibilities for exploring grief, and memory regarding marginalized experiences, allowing discussions on topics of intersectionality and challenging societal expectations on processing collective loss. Editor: Indeed, it speaks to how symbols and images have always been key for humanity grappling with loss and mortality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.