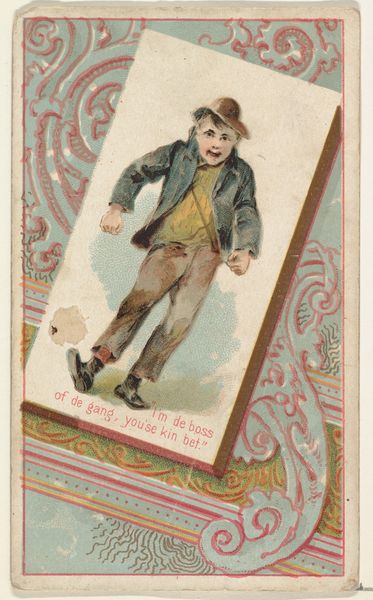

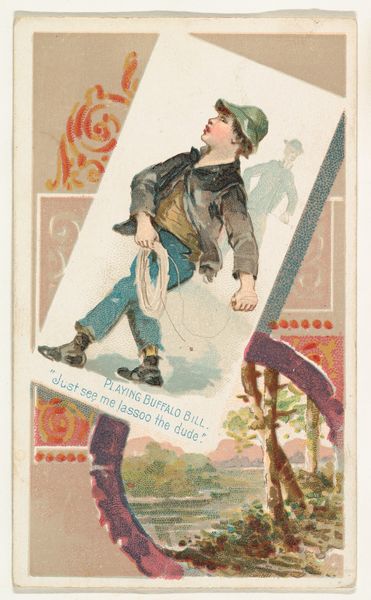

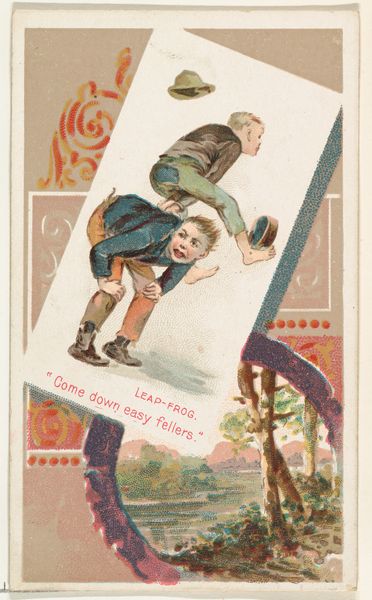

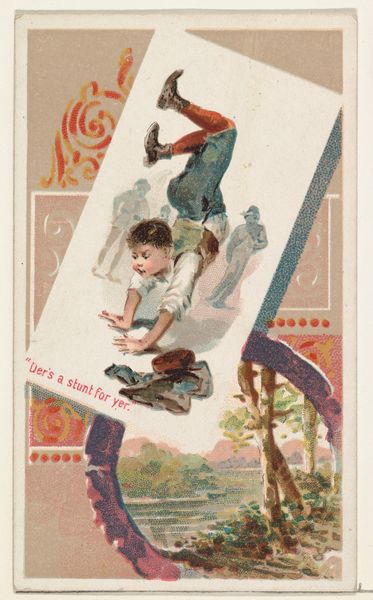

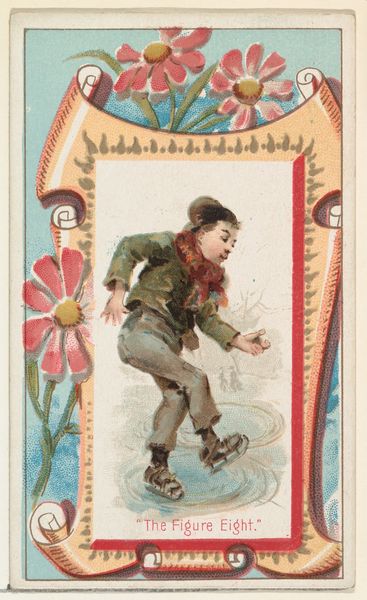

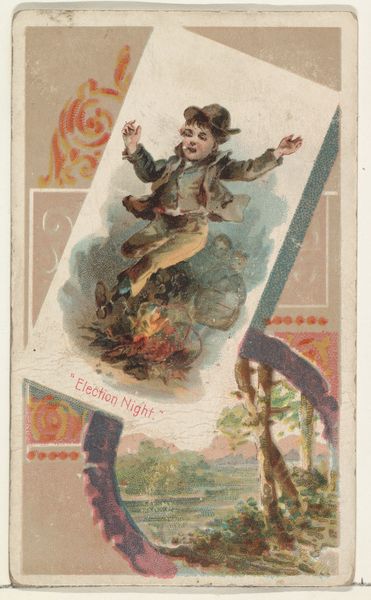

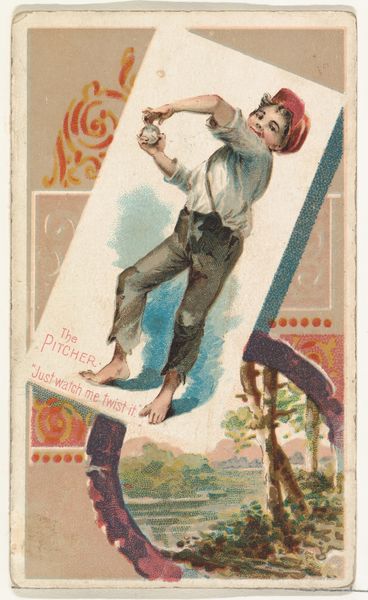

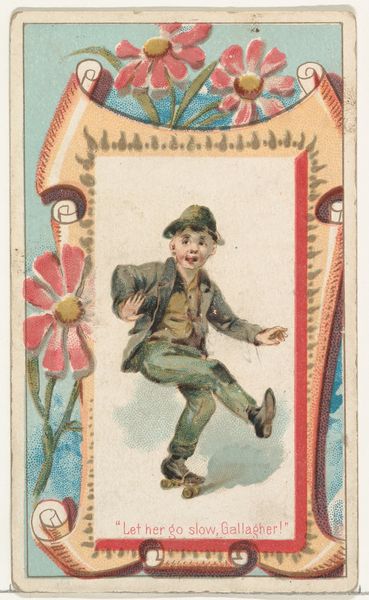

"I'm de boss of de gang, you'se kin bet," from the Terrors of America set (N136) issued by Duke Sons & Co. to promote Honest Long Cut Tobacco 1888 - 1889

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

water colours

# print

#

impressionism

#

caricature

#

coloured pencil

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Well, this is certainly striking. The work before us, titled "I'm de boss of de gang, you'se kin bet," hails from the Terrors of America set, a promotional series by Duke Sons & Co. for Honest Long Cut Tobacco, dating from around 1888 to 1889. It employs print and colored pencil, and it's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is pure energy. The figure, though small, is dynamic, almost leaping off the card. It’s scrappy and bold, despite the obviously humble materials used in its creation. Curator: Yes, and the deliberate use of colored pencil and print is fascinating. Think about the industrial process: the mass production of these cards, distributed with tobacco, speaks to the democratization of art in a way. It's not a rarefied oil painting, but something readily accessible, cheaply produced and distributed, becoming interwoven with daily life. Editor: The phrase “Terrors of America” and this kid's claim – it evokes a particular era of social anxiety. The turn of the century saw lots of new concepts of juvenile delinquency. But it's interesting the artist or company has put a comical image with this new fear: what is it supposed to signal, or calm, I wonder? Curator: Absolutely. And think of the consumer. Smoking tobacco wasn’t simply about the act of consumption, but also about participating in a wider culture, sharing these images, perhaps even collecting them. What meaning did workers and factory employees take in seeing the means of cultural and financial production made plain? Editor: Symbolically, it's a brash assertion of power. The child’s posture and expression – exaggerated, almost cartoonish – it reads as an ironic or defiant challenge to authority. The use of dialect, too, paints an idea, almost an advertisement for poverty. This must have tapped into pre-existing anxieties about class, childhood, and the perceived loss of social order at the time. Curator: Indeed. And to go back to the materials, consider how the disposability of these cards contrasts with the grand artistic traditions they mimic, how this challenges the definition of high art. They quickly end up forgotten or cast aside, thus mirroring the children they claim to represent: disregarded and thrown away. The colors also show, at moments crude but full of vibrancy; they reflect the chaotic environment this "boss" probably inhabits. Editor: That’s an insightful way to look at it. Ultimately, I think, its power comes from capturing the spirit, albeit through a distorted lens, of a particularly turbulent period. Thanks to this analysis, my perspective on that turbulence has deepened. Curator: And by examining the card as both an aesthetic object and a commodity, we begin to grasp the complex interplay of art, labor, and society it represents, giving nuance to its lasting symbolic meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.