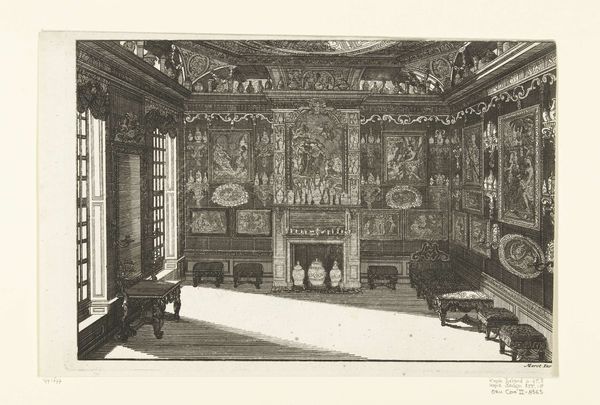

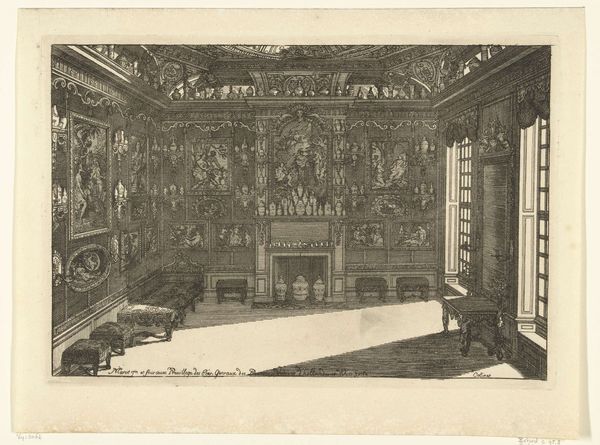

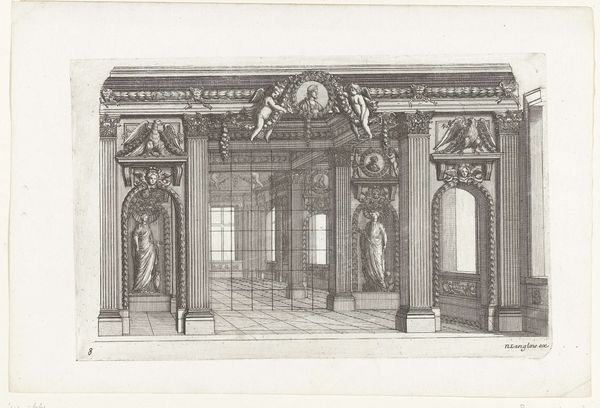

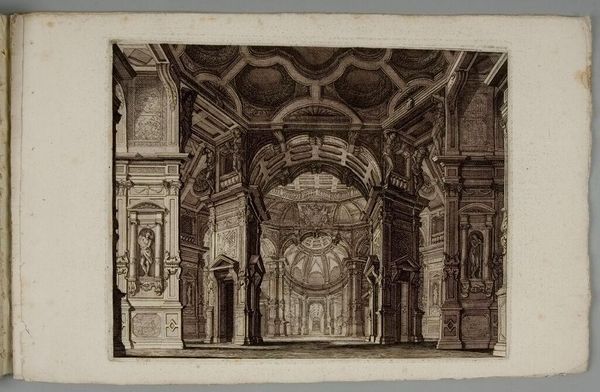

Toneel van de Amsterdamse Schouwburg aan de Keizersgracht te Amsterdam 1664

0:00

0:00

janveenhuysen

Rijksmuseum

print, ink, pen, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 133 mm, width 156 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes you first about this image? To me, the meticulous detail gives a real sense of occasion. Editor: The weight of it, actually. So much darkness pressing in. Is it supposed to feel celebratory? It feels somber and shadowed. Curator: It's an engraving from 1664, titled "Toneel van de Amsterdamse Schouwburg aan de Keizersgracht te Amsterdam" by Jan Veenhuysen, depicting the interior of the Amsterdam Theatre. As an iconographer, the symbolism here is rich. Theatre, even the architecture of theatre itself, has been symbolically associated with stages of life, dramatic tensions, and public rituals. The imposing architecture itself mirrors the Baroque ideals of control and grandeur. Editor: Grandeur certainly, though that theatrical control… the history of the Amsterdam theatre is far from controlled. Political uprisings, religious clashes. This engraving exists, I would argue, as a form of social memory, meant to portray order even in the face of chaos. What looks static to our modern eyes was then teeming with conflicting meanings. Curator: You see the image through the lens of turbulent history, I observe how theatre as a cultural symbol provides an emotional outlet. Look at the allegorical figures flanking the central panel – guardians of artistic expression. Are they not comforting? Don’t they suggest a haven, a protected space within a chaotic world? Editor: Haven is a generous word. Censorship plagued performances, social unrest often spilled onto the stage… Curator: True, and I wouldn’t suggest a pure escape, more a carefully constructed reflection. An ordered world mimicking life’s disorder, where deep seated emotions were both roused and ultimately contained. Isn't that paradox key to unlocking our experience with drama itself? Editor: Perhaps the order offered in the building then helped reflect social strata rather than contain dangerous emotions. How the seating was structured, who could participate, who were merely allowed to witness and observe – every play and event became a mirror for class division. Curator: Very well, consider instead the universal aspect. The performance in this engraving has ended. The stage is bare and thus symbolically receptive – primed for both tragedy and joy. What play will humanity enact here? Editor: And who will be writing the script, and for whom… that, I believe, is the question history forces us to ask of even the most seemingly benign of images. Curator: Indeed. Seeing beyond surface, to deeper significance – it is the play in which we're both endlessly engaged.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.