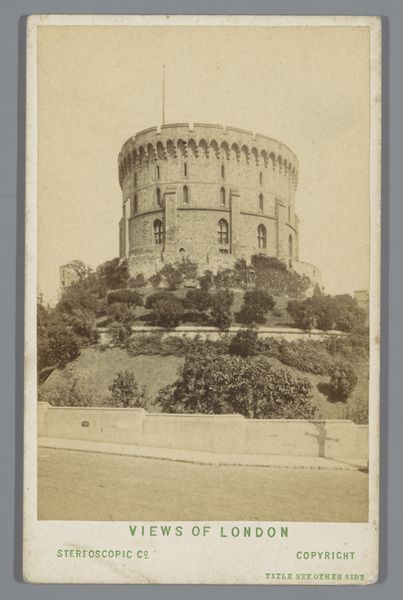

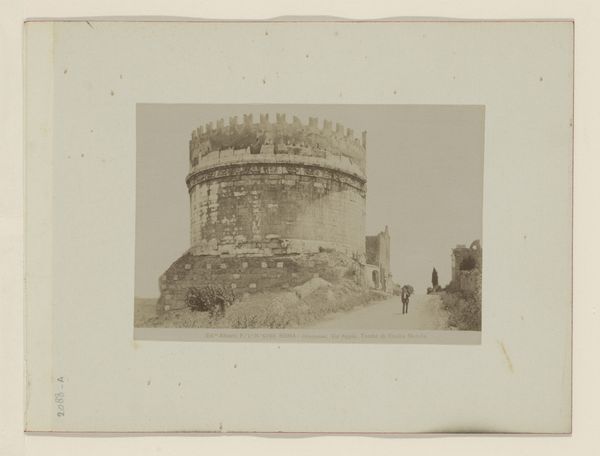

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

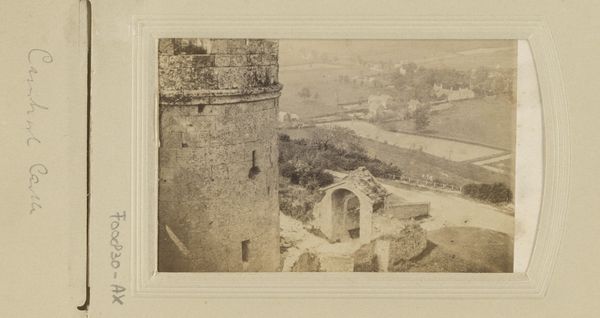

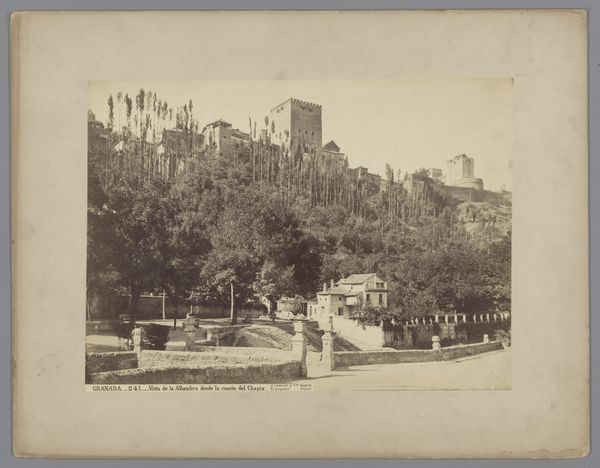

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

architecture

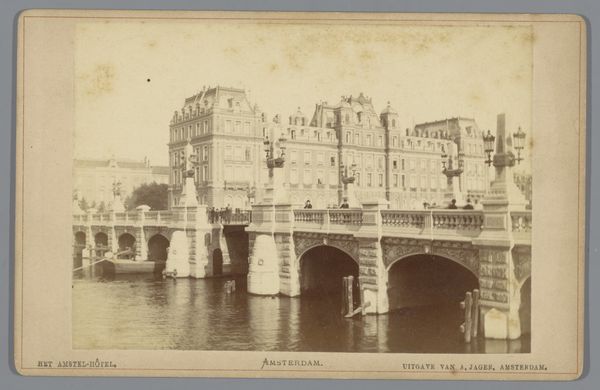

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 3/4 × 8 1/8 in. (17.1 × 20.7 cm) Image: 5 13/16 × 6 7/8 in. (14.8 × 17.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us we have William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1841 daguerreotype, "Windsor Castle," currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It's immediately striking how ethereal and somehow intimate this photograph feels, even with such a monumental subject. The tones are warm sepia and the soft focus almost romanticizes the imposing architecture. Curator: Talbot's work here is pivotal. As a pioneer of photography, his calotype process allowed for multiple prints from a single negative. That innovation shifted photography from a mere novelty to a tool for mass communication and documentation. Editor: Absolutely, and it makes me consider the power dynamics inherent in capturing such an iconic symbol of British power. Here we see Windsor Castle, but reproduced and available. How does that democratizing potential alter the castle’s inherent associations? Curator: It's a fascinating question. While the calotype opened up wider access, consider the original audience. Were these images intended for political commentary, or as artistic studies playing into a certain fashionable Romanticism and the picturesque aesthetic of the era? The inclusion of the tiny horse-drawn cart invites contemplation on human scale amid structures of authority. Editor: True, the Romantic ideals come through, and yet I am stuck with the thought that the photographic image, even this early version, subtly undermines the concept of singular, unquestionable authority through mass reproducibility. Each print destabilizes a bit more. Curator: That friction is precisely what makes Talbot's work so enduringly compelling. He captures an emblem of stability while employing a technology primed to destabilize fixed notions and democratize visual culture. Editor: It invites us to rethink power and representation, not just within the frame, but outside of it. The way history is created, recorded, shared, and contested through imagery remains crucial. Curator: Agreed. It reminds us that even the most traditional institutions are constantly being renegotiated in relation to changes in media, technology, and culture. Editor: This makes me wonder, how would it look in a modern rendering? That’s something worth thinking about, how perceptions change throughout history and human advancements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.