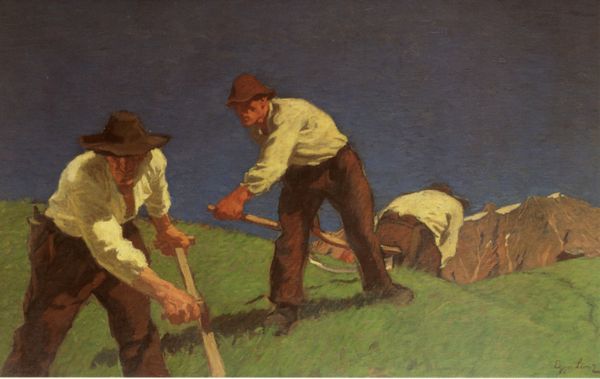

Dimensions: 111.7 x 81.2 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately about Jean-François Millet's "Peasant Spreading Manure," painted in 1855, is how earthy and, frankly, unromantic it is. Editor: Earthy is right. It’s less about idyllic farmland and more about…well, the materials. You see the peasant laborer, rendered with dignity, but what I can't stop looking at is what he’s spreading. Actual manure. Not something you typically find in “high art”. Curator: Precisely. And that challenges our notions of beauty and worth, doesn’t it? Millet uses the peasant figure almost as a Christ-like symbol. Spreading manure might not seem glamorous, but consider the cycle of life embedded in that simple action: death and decay fertilizing new growth. This embodies deep cultural and religious understanding about death and resurrection. Editor: The means of production become the subject matter itself. Look at his simple clothing and those worn clogs. They're testaments to the back-breaking labour. Also, what about the paint itself? The way the ochres and browns build texture mirrors the richness, maybe even the thickness, of the manure being spread across the field. He doesn’t shy away from the messy realities of agriculture. Curator: Messy, yes, but also full of a strange kind of holiness. Note the setting sun, how it almost halos the figure of the peasant. He's engaged in profoundly meaningful, if unglamorous, labor, intimately connected to the soil, to sustenance, to a way of life quickly vanishing even at the time of its creation. And the other figure, she fades into the background, shrouded. They're emblems of generations. Editor: Vanishing, but consumed. Because, ultimately, the product of this labour is food on someone’s table, whether that someone acknowledges it or not. There’s a social dimension that’s unavoidable. How and by whom is food produced, and who profits from it? Even in its quiet pastoral guise, the painting suggests hierarchies, consumption, labor value and waste in early industrialising Europe. Curator: It prompts consideration, then, of both the tangible and the symbolic weight embedded within seemingly simple agrarian practices. The peasant isn't just a worker; he's a symbol of our connection to the land, to our origins. Editor: And of a system of materials, production, labor and, let’s not forget, waste. Looking at this has only reinforced how inescapable it all is.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.