sculpture, marble

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

marble

#

realism

#

statue

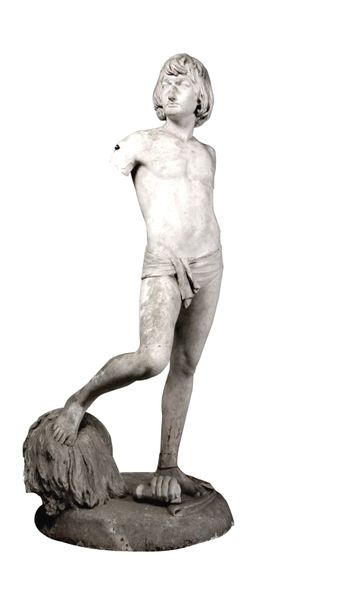

Dimensions: height 94 cm, weight 175 kg, width 43 cm, height 126 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a marble bust identified as Titus Flavius Domitianus, likely created after 1674 by Bartholomeus Eggers. What strikes you most about it? Editor: Power. There's a palpable sense of authority radiating from this weathered stone. The slightly downturned mouth, the set jaw – it all speaks of someone accustomed to command. It’s not idealized; there’s a very human weight in the face. Curator: You've picked up on something quite interesting there. The portrait plays with the public image of Domitian, the last Flavian emperor. Though the sculpture appears classical, bearing a wreath symbolic of Roman leaders, Eggers crafted it well after Domitian's death, during a period when the emperor’s reputation was undergoing complex re-evaluations. Editor: I see it in the details. That laurel wreath, while traditional, is almost…uncomfortable looking. It’s bulky, less graceful than wreaths depicted in earlier Roman art. There's a visual tension between the idealized symbolism and the very tangible humanity in the emperor's face. Are we meant to respect or question his authority? Curator: Precisely. It invites the viewer to engage critically. Domitian’s reign was followed by an official condemnation, but later historical scholarship has painted a more complex picture, citing his effective governance. Editor: So the sculpture becomes a site for negotiation, visually grappling with Domitian's legacy centuries after his death. The wear on the marble itself adds another layer of complexity. The statue appears aged, almost crumbling; like memory it is flawed, yet permanent. Is he remembered with veneration or scorn? Curator: Absolutely. It’s a tangible reminder of the ongoing process of historical revision. Eggers uses the visual language of power – Roman portraiture – but subtly undermines it. Consider too, that portraiture itself was often used to shape perceptions and control public opinion during the Roman empire. This piece echoes that and comments on it from afar. Editor: It speaks volumes, doesn't it? The sculpture manages to be both a historical artifact and an active participant in an ongoing conversation about power, memory, and historical truth. A quiet statement about how even empires decay and are rewritten over time. Curator: I couldn't agree more. It is precisely that resonance with contemporary conversations about power that gives it its enduring impact.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Bartholomeus Eggers was commissioned in 1674 to make twelve marble busts of Roman emperors for the grounds of Oranienburg Palace near Berlin. Some of these busts resemble the four lead portraits in the Rijksmuseum garden. Presumably, the models that Eggers made were acquired by a metal caster, who used them to make these lead versions.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.