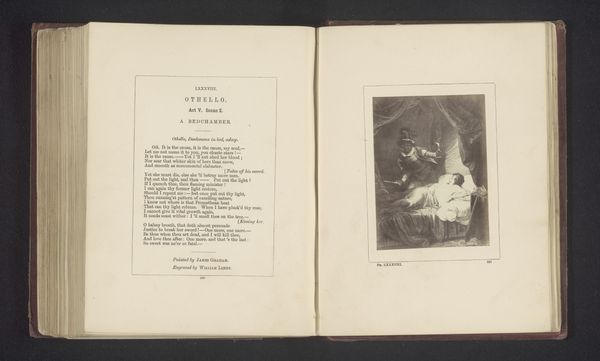

Fotoreproductie van een prent naar een schilderij door Richard Westall, voorstellend een scene uit Cymbeline door William Shakespeare before 1864

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

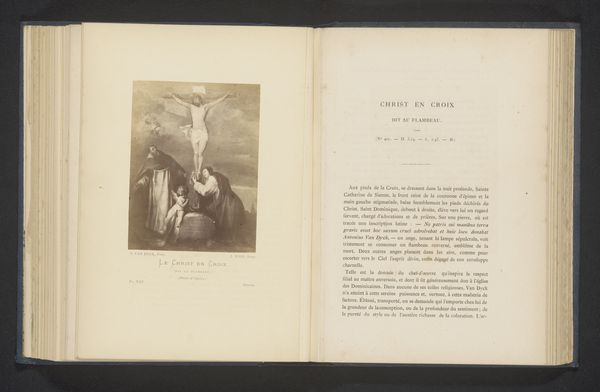

Curator: I am struck by how theatrical this composition feels. There is a powerful and unsettling tension emanating from the solitary figure positioned against what seems like a gaping cave. Editor: Absolutely, the staging and lighting play crucial roles in creating that unease. What we’re looking at is a photographic reproduction of a print, after a painting by Richard Westall. The artwork’s title is quite a mouthful: “Fotoreproductie van een prent naar een schilderij door Richard Westall, voorstellend een scene uit Cymbeline door William Shakespeare,” or, a photographic reproduction of a print after a painting by Richard Westall, depicting a scene from Shakespeare’s “Cymbeline”. It likely dates from before 1864. Curator: Interesting. Considering it's a reproduction, I wonder about the materials and methods of production used at that time. What kind of paper, inks, and photographic techniques were accessible, and how would those processes reflect socio-economic conditions in England at the time of production and reproduction? Were these mass-produced for widespread consumption or printed on demand, serving an exclusive clientele? Editor: Locating this print within its 19th-century context helps us decode its layered social meaning. Shakespeare was elevated to near-mythical status during the Romantic era; images and artworks related to his work functioned almost like political statements and declarations of identity. Who had access to Shakespeare, in what forms, and under what conditions? This image's very circulation speaks volumes about cultural values during this period. Curator: True, access to culture remains a key aspect. Looking at it through a modern lens, I also wonder how much of Westall’s original intent survives translation through all these layers. How does photographic reproduction impact our reception of his composition? Does it flatten the artist’s labor by further removing their hand? Editor: It almost certainly does. Considering this specific moment in the Victorian period—with its stark class divides and England’s imperial exploits, it’s difficult not to read that dramatic shadow within the cave as symbolic, representing something like England’s shadow self as seen through a colonial or post-colonial gaze. Curator: It gives us pause, indeed. I keep returning to the subject position though. What did it mean to consume reproductions of fine art when original artworks were only accessible to a very few wealthy people? Was it seen as an equivalent experience, or simply as a consolation prize? Editor: It provided access, of a certain sort. Ultimately this work, like others, provides such a rich landscape for inquiry, for analyzing and thinking through questions of identity and historical forces. Curator: Precisely. Examining artmaking as a means of knowledge production enables us to understand culture, labor, and even individual experience in exciting new ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.