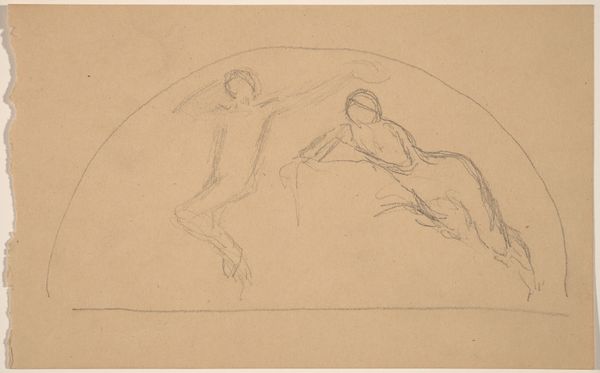

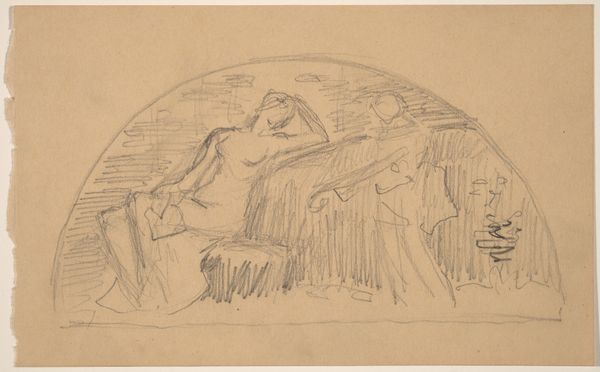

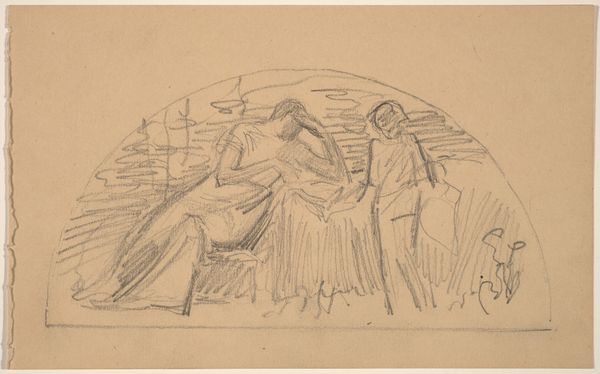

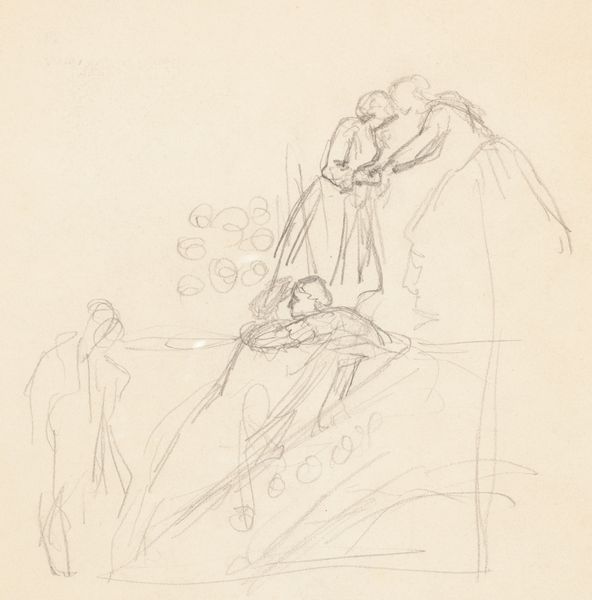

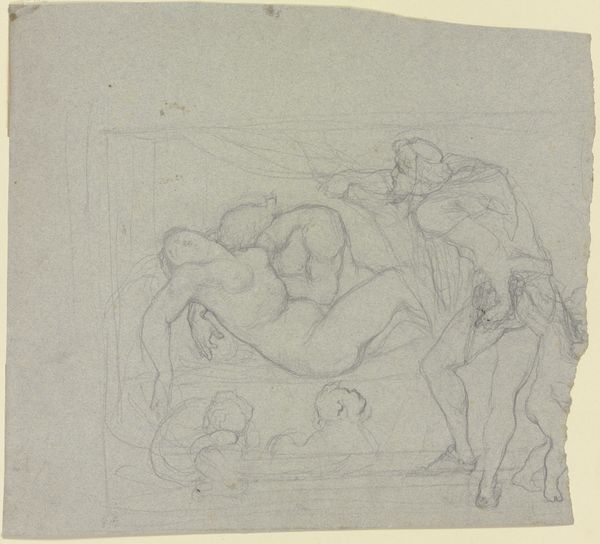

drawing, pencil

#

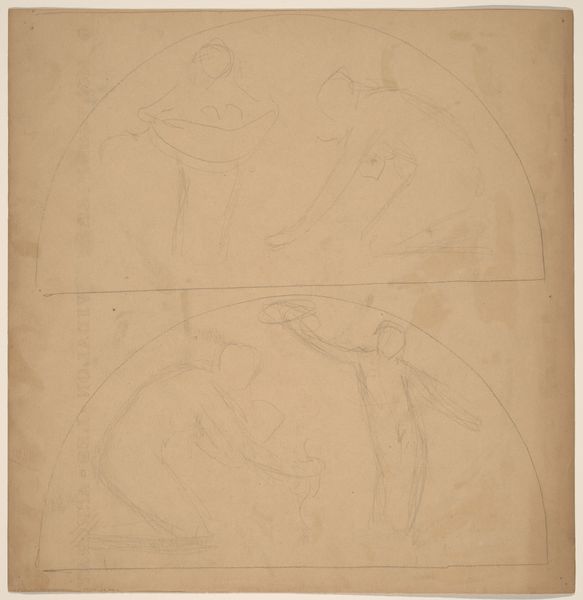

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

academic-art

Dimensions: sheet: 11.7 × 18.8 cm (4 5/8 × 7 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This pencil sketch, titled "Study for a Lunette," was created by Charles Sprague Pearce sometime between 1890 and 1897. What are your first impressions? Editor: Well, the figures are lightly sketched, almost ghostly, within this arched space. It gives me a feeling of fleeting moments, something remembered rather than concrete. Curator: That's interesting. The lunette shape itself, the semi-circular format, historically carries religious and allegorical significance, especially in architecture. Pearce was working during a time when academic art was grappling with traditions—how might this inform our understanding? Editor: Considering the historical context, one might ask if Pearce aims to reinterpret classical forms? Is this an exploration of, or perhaps a subtle critique of, the weighty expectations associated with public art? It makes me wonder, for whom was he preparing to make this lunette, and where? Curator: Good questions! The loose sketchiness softens any sense of grandiose authority. Yet, these forms remain, echoing back to those artistic roots. Looking closely, that central figure with arms outstretched feels familiar—could Pearce have been invoking the visual language of triumphant figures or even allusions to classical theatre, gesturing at symbolic meaning? Editor: Yes, perhaps referencing figures like Nike or classical theatrical gestures, both conveying emotional drama. I see a dancer, evoking human gestures representing triumph and perhaps grief or burden, reflected in the posture of the other, bowed, figure. These gestures would be understood broadly across cultures, wouldn't they, becoming accessible to wider audiences, which academic art very much considered in those days? Curator: Indeed, public art during the late 19th century became an exercise in communicating values to ever-expanding, newly mixed urban populations. An artist like Pearce navigates tradition and accessibility, carefully orchestrating symbols within a semi-circular boundary, that shapes not only what is being expressed but who is seeing and reading. Editor: I come away feeling these delicate lines point towards wider conversations, both aesthetic and political, concerning access to public art and the symbolism it employs, even in an unfinished study like this. It offers a glimpse into Pearce's working through those ideas. Curator: Absolutely. We witness a crucial negotiation between old forms and the emerging needs of a public-facing art that’s happening in the period and get the feeling that academic art wasn't so dogmatic as is often now portrayed. It was still feeling its way in the modern age.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.