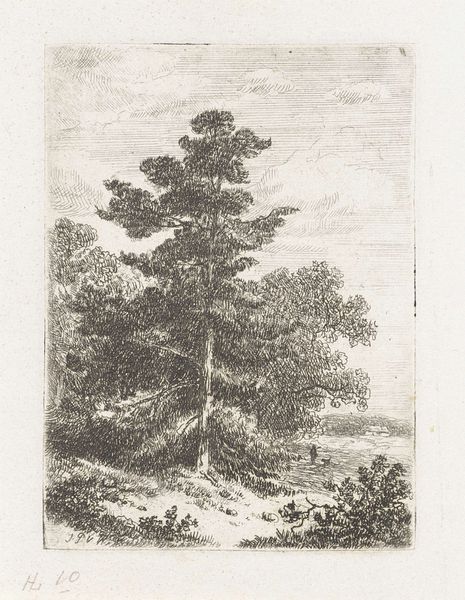

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

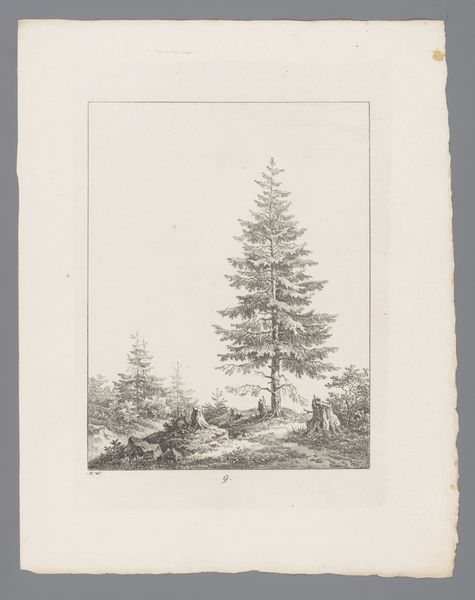

Curator: This is Johannes Pieter van Wisselingh’s “Landschap met drie sparren,” created sometime between 1830 and 1878. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s an etching, so let’s consider it primarily through the lens of line and form. What stands out to you upon seeing it? Editor: The first thing I notice is its peaceful stillness. Despite being rendered only in black and white lines, it conveys a remarkable sense of serenity and quiet observation. There's almost a photographic quality to the scene despite the artist's intervention. Curator: I’m glad you picked up on that stillness. Trees in art carry the weight of various symbolic interpretations. In this image, though, I’d say their towering presence and rootedness evoke feelings of permanence and steadfastness. The artist seems particularly concerned with the symbol of resilience against the vicissitudes of existence. What is particularly powerful about trees as symbols is how universal the appeal is. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about the pure formal properties though, what draws me is the sheer range of textures Van Wisselingh achieves using only etching techniques. Look at the density of lines suggesting foliage compared to the delicate, horizontal strokes indicating the sky. He's mastered how to mimic depth and light with incredible economy. The human figure introduces the essential semiotic, scaling the image in order to represent natural space in proportion to an accepted understanding. Curator: Exactly. Landscape as a concept is intertwined with our perception of self within space, it suggests solitude and exploration. Editor: And the contrast is crucial. I’d go even further to propose that it presents not just exploration, but control over an image of the world, reduced and easily accessed through ownership. To the cultural imagination of the nineteenth-century man, control over an aesthetic like this extended to imperial attitudes towards conquest and extraction. This makes it hard for modern sensibilities to appreciate fully as simply serene, peaceful, or objective. Curator: That’s an important point—recognizing the lens of the time through which such pieces were created allows a viewer to really understand all its levels, rather than taking a work at face value. Editor: I'm glad you agree. Appreciating not just *what* is depicted but *how* helps reveal those complexities. Curator: Seeing how cultural narratives become etched not just onto metal plates, but onto our collective psyche adds so much value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.