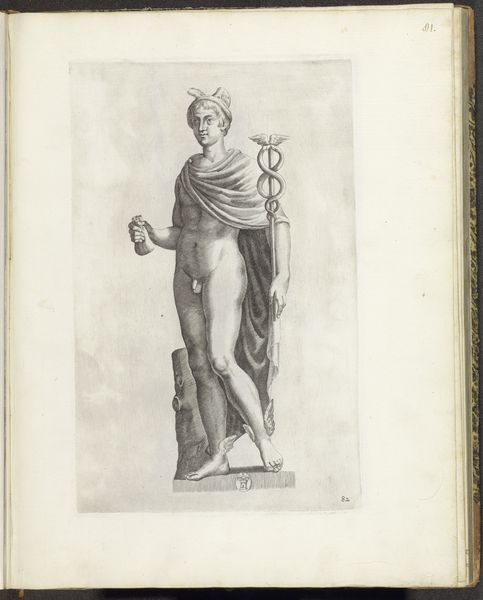

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

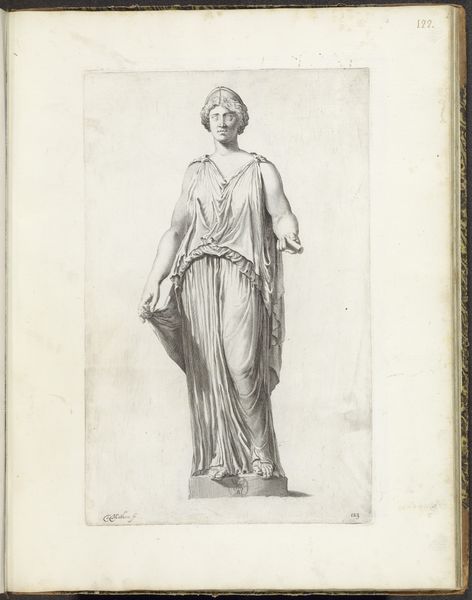

Dimensions: height 371 mm, width 230 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

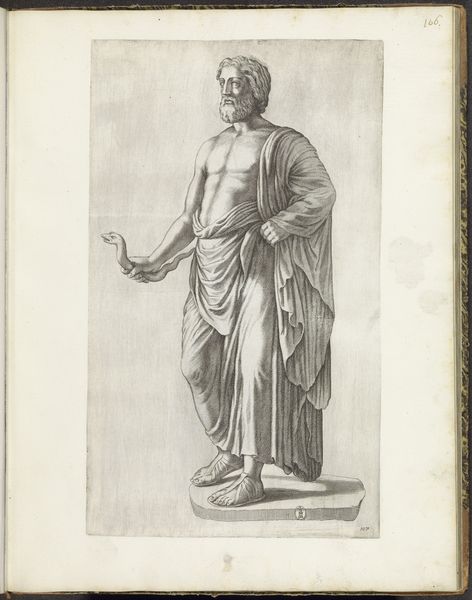

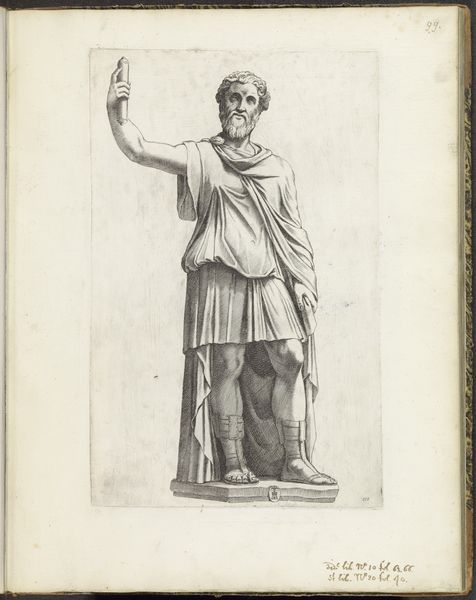

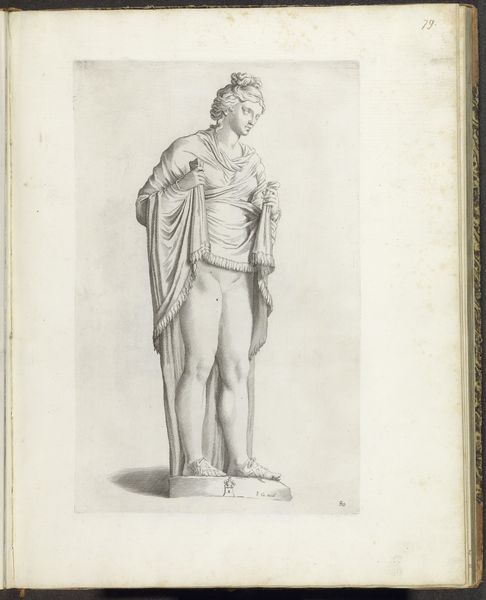

Editor: This is "Statue of Jupiter," a pencil drawing by Cornelis Bloemaert, created sometime between 1636 and 1647. I'm struck by the detail in the rendering of the fabric and muscles – it feels incredibly lifelike for a drawing. What can you tell me about it? Curator: I see a very careful, deliberate process here. Look at the precision in the shading, the almost mechanical reproduction of classical ideals. It speaks to a system, a workshop perhaps, where such drawings were not just art, but a form of visual documentation, of translating the grandeur of sculpture into a reproducible commodity. How do you think the choice of pencil, versus ink or charcoal, affects our perception of its value? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way. The pencil gives it a sense of accessibility, almost like a blueprint rather than a finished piece of art. Perhaps it was more about the utility of capturing the image accurately, for later use, than creating a precious object? Curator: Precisely. Consider the socio-economic context: the demand for classical imagery, the rise of printmaking, and the role of drawings like these in disseminating those images. The paper itself, the cost of the pencil – all contribute to the value and meaning of this work. How does understanding it as a product of its time, made using specific, readily available materials, change your initial impression of its 'lifelike' quality? Editor: It makes it less about individual genius and more about skilled labor and access to resources. It's interesting to think about the "means of production" even in something that appears so classical and refined. Curator: And in doing so, it opens a broader investigation on consumption. So what do you take from it now? Editor: I’m definitely seeing it differently now – less as an isolated masterpiece, and more as a record and a tool shaped by the materials available to Bloemaert and the needs of his patrons. It gives us a more detailed picture of 17th century art creation. Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.