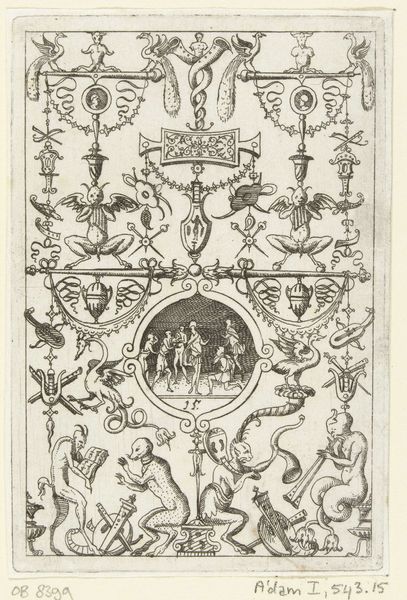

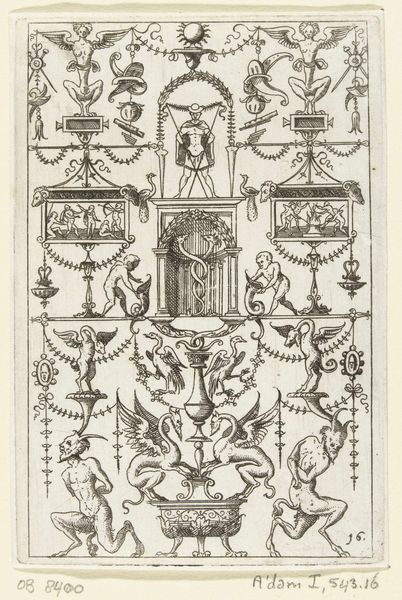

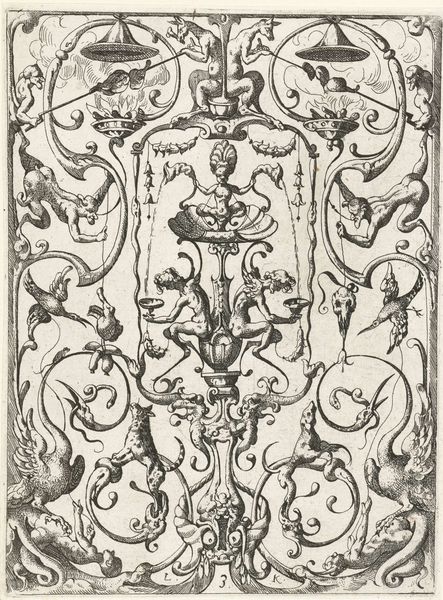

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 69 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a pen illustration titled "Kandelaber, onderaan zit een sater gehurkt tussen twee honden," which translates to "Candelabra, underneath sits a satyr squatting between two dogs." It's attributed to Hans Sibmacher and dates from about 1525 to 1594, rendered in ink on metal. Editor: My immediate impression is how unsettlingly decorative it is. It's busy, baroque, and the satyr figure at the bottom creates a discordant, almost lewd energy within this supposed design for a candelabra. Curator: Well, that tension is precisely what makes it fascinating. Considering it was likely intended as a model for metalwork, perhaps even jewelry, it provides insights into the material culture and consumption of such luxury goods in Renaissance Europe. The choice of metal, the meticulous engraving—it speaks to a specific market valuing both artistry and opulence. Editor: Precisely. And we can’t ignore the socio-political implications embedded in these images. A satyr, for instance, isn’t just a decorative motif. It invokes classical mythology but filtered through a Christian lens – often coded as a symbol of base desire, masculine excess, even deviance. Placing it alongside the domesticated dogs creates a stark binary, policing boundaries between civilized and uncivilized. Who was commissioning such work and what cultural values were being reinforced? Curator: I'd argue the ambiguity is deliberate. Sibmacher’s clever use of ink lines suggests a three-dimensionality, pushing the boundaries between image and object. It challenges what we understand as a utilitarian design by layering pagan imagery with religious undertones and intricate ornamentation. It might hint at an environment where classical and Christian symbology were fused for display, ritual, or a combination of the two. Editor: Yes, but even the very act of creating prints – and distributing these images—indicates something. It shows an increasing accessibility, if not ownership, of these cultural narratives. Who now can own this “deviant” or mythological candelabra and what impact will the image have within private domestic spheres? Curator: Exactly. And when you consider the laborious process of engraving and the skills required, we can recognize how specialized the field must have been during this period and why craft guilds held such prominence. The details in the line work show the hand of a master craftsman. Editor: It compels us to consider these supposedly ornamental objects, like candelabras, as reflections of Renaissance power dynamics, beliefs and social codes. It opens up important conversations about visual representation and its ongoing relationship to the politics of seeing. Curator: A beautiful and intriguing confluence of skill, process and society captured in this little print, I would say. Editor: Indeed, a lot of ideas for such an initially unassuming piece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.