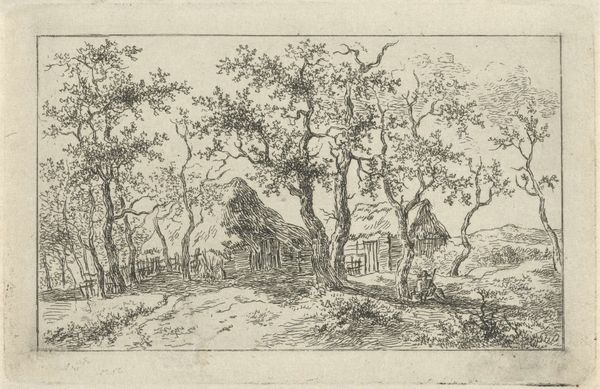

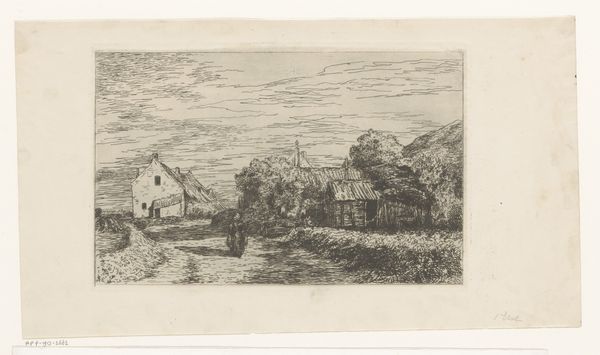

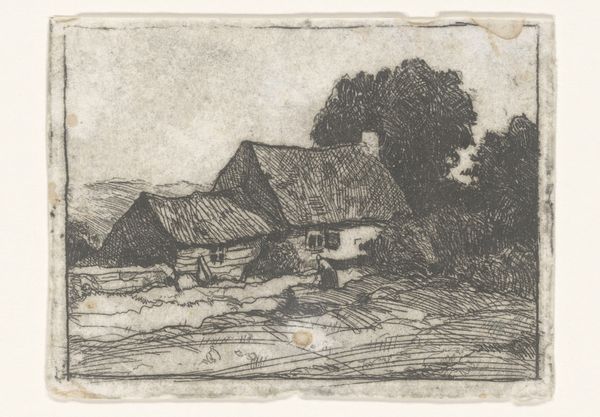

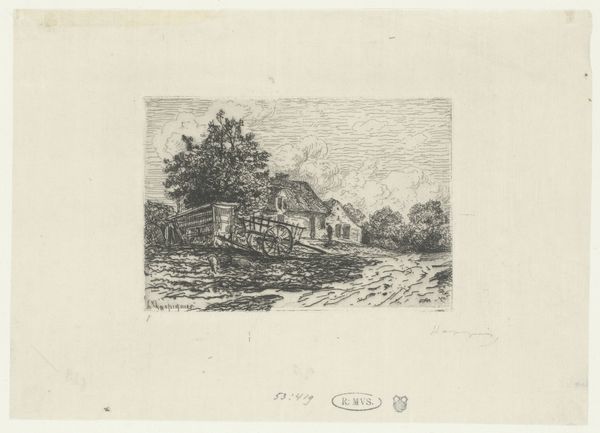

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ink

#

realism

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 3 1/8 × 4 5/16 in. (8 × 11 cm) Plate: 2 7/8 × 3 15/16 in. (7.3 × 10 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is Charles Jacque’s etching, "Landscape with Hovels," created in 1846. Editor: It's immediately striking – a network of tightly interwoven lines capturing a rather bleak scene, isn't it? The textures feel coarse, almost tactile. Curator: The texture arises from Jacque's mastery of etching. Note the deliberate use of line weight and density to delineate form. See how the heavy lines give a strong form to the structures, setting against the lighter marks depicting sky? Editor: Absolutely. The contrast establishes a spatial depth – pushing back beyond the houses. These hovels though – there's an unmistakable air of rural poverty clinging to them. Were Jacque’s prints shown in public venues in this period? How might audiences have received such scenes? Curator: The density certainly plays a role in mood. His contemporary viewers likely understood Jacque as representing rural peasantry. However, to see him only as a recorder of the peasantry would be an oversight. Examine the structural coherence of the whole piece – see how forms intersect, how they inform other forms. Editor: Agreed, one can't deny his technical skills. The little windmill is particularly nicely evoked in a few brief strokes, but his depiction would clearly have signaled a certain level of class consciousness to urban audiences of the era. Was Jacque a critic? A sympathizer? What position did his prints create for audiences? Curator: A certain political dimension, clearly. However, in focusing on its social position and function, you run the risk of reducing its purely aesthetic merit. For instance, observe the rhythm created by the roofs, the buildings and bare trees across the plane, how the horizontal hatching establishes ground and a sense of balance between the solid landscape. Editor: A valuable perspective, yet such choices, too, shape public sentiment, regardless of conscious intentions. The picturesque could easily conceal as much as it reveals about the people of 19th century France. Curator: A painting’s function, though, evolves historically as contexts shift. Viewing "Landscape with Hovels" today gives us opportunity to appreciate line, form, tonal gradations - elements of print-making which speak volumes without external explanation. Editor: Perhaps what truly resonates is art's capacity to transcend specific context and continuously shape public conversation, whether focused on structure or historical experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.